Contents

Guide

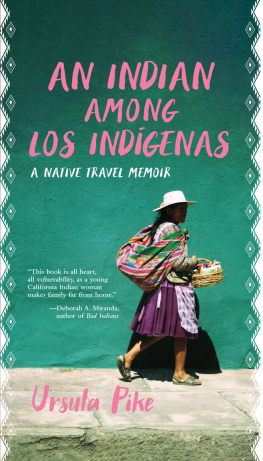

Copyright 2021 by Ursula Pike

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pike, Ursula, 1968- author.

Title: An Indian among los Indgenas / Ursula Pike.

Description: Berkeley, California : Heyday, [2021]

Identifiers: LCCN 2020030725 (print) | LCCN 2020030726 (ebook) | ISBN 9781597145275 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781597145282 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Pike, Ursula, 1968---Travel--Bolivia. | Peace Corps (U.S.)--Biography. | Peace Corps (U.S.)--Bolivia--History--20th century. | Karok women--Biography. | Indians of South America--Bolivia--Social conditions. | Indians of North America--California--Social conditions. | Bolivia--Colonization.

Classification: LCC HC60.5 .P53 2021 (print) | LCC HC60.5 (ebook) | DDC 362.6283/9998084 [B]--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020030725

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020030726

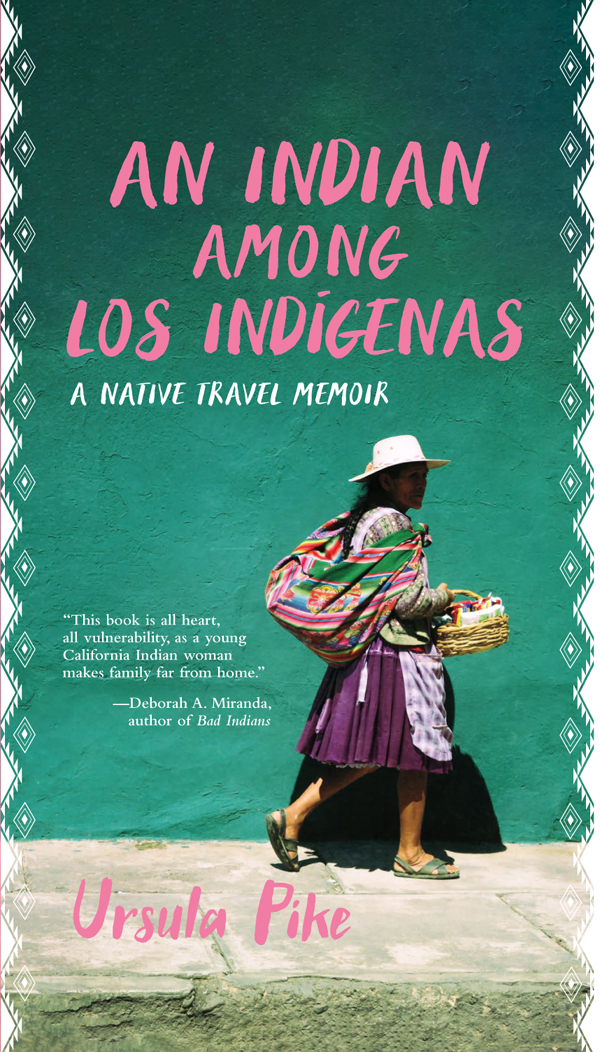

Cover Photo: Ral Barrios

Endsheet Photo: Valentina Alvarez

Cover Design: Ashley Ingram

Interior Design/Typesetting: Ashley Ingram

Published by Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, California 94709

(510) 549-3564

heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Preface

Brooklyn Elementary School in southeast Portland, Oregon, had a special Thanksgiving celebration the year I was in third grade. Earlier that week, a man came to the school to teach us about the potlatch tradition of the Pacific Northwest Indians. This middle-aged white man overenunciated in the way adults do when they are explaining very important things to children. Potlatch came from a Chinook word meaning to give, and although it sounded like potluck, it was different. A traditional potlatch ceremony included feasting and gift giving. The more a family or a chief could share at the potlatch, the more important they were. The giving was the important part. Sharing their wealth also cemented important connections between families.

I had never heard of a potlatch. I am a member of the Karuk Tribe, from the steep mountains near the California-Oregon border, but I had also never ridden a horse, shot an arrow, or slept in a teepeethings I thought all Indians were supposed to have done.

Our teachers decided that each class would have our own potlatch before going on break, so we made headbands and attached construction-paper feathers. Some of the girls braided each others hair. My mother almost never braided my hair even though it was long and straight, because of enormous tangles I never let her brush out. All the students and the teachers sat on the gyms wood floor in a big circle. The man played a hand drum slowly and told a story. I sat on the hard floor, thinking of what I could give as part of the potlatch. I was looking forward to the Thanksgiving break because my mom, my sister, and I were driving to my grandparents house in Daly City, California. We often stopped in Yreka, the halfway point of the eight-hour drive, where my auntie Mary always greeted us warmly at the door no matter what time we knocked.

Does anyone have any gifts they would like to give? the man asked the circle. I nearly dislocated my shoulder in an attempt to be the first one to raise my hand. I was eager to show that I had absorbed the lesson of the potlatch and could perform the version of nativeness he had presented to us.

He gave me the nod and I stood up. Making elaborate hand gestures in hopes that they added to the realness of my performance, I offered an imaginary chicken to my friend across the circle. I watched the man the whole time I was talking, wanting him to affirm that I was doing it correctly. My friend on the other side of the room looked at me with confusion in her eyes.

Say thank you, the man told her. She mumbled her gratitude for the nonexistent chicken. Standing in front of the class was embarrassing, but I was also uncomfortable because I knew I was performing an identity that looked nothing like my actual life. There was no confusion in my mind about being Karuk, but up there in front of my classmates, I thought I had to act the way he told me Indians acted. I understood that there was the real life I lived and then there was the version of American Indian everyone expected. When the exchange was over, I sat down with relief. Other children stood up and offered imaginary gifts to each other as the man coached them through the exchange. When the potlatch finally ended, I left the gym quickly, happy to be released into my real life.

My family repeated stories of Spanish, Irish, and even Cherokee ancestors, but the language my grandmother spoke to her mother was Karuk, and the culture I was taught to claim was Karuk. Unlike my grandmother, I didnt grow up near the confluence of the Klamath and Salmon Rivers. My playgrounds were in the cities of Oregon and Washington State, and I learned to ride my bike in the parking lot of a Laundromat in Portland. I know the sometimes-bitter flavor of xuuna traditional acorn porridgebut I dont know how to gather acorns.

Half of what I know about my tribe comes from the stories my grandmother told me and the songs that were sung around a campfire on the river. The other half comes from books written by anthropologists. However, all of my knowledge about being an urban Indian growing up in a city comes from my lived experience. It comes from attending Portlands Delta Park powwow on the flat space off Interstate 5, where I played tag with other kids until it was too dark to see. It comes from hearing my mothers stories about working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs on reservations throughout the Pacific Northwest. I knew Native construction workers, tribal council members, fry cooks, and botanists. My understanding of what it meant to be Native also came from sitting in a student meeting during college where American Indians from different tribes, all with their own traditions, planned a powwow. My experiences and these people were never represented in the books I read or movies I saw, but they were whom I thought of when I heard the word Indian.

American Indian was the box I checked when I applied to college and on my Peace Corps application. When I went to Bolivia as a twenty-five-year-old Peace Corps volunteer, I knew it was a country full of Indigenous people. I wanted to help Indians. But I didnt realize that helping people is difficult. The understanding that the giver is better off than the receiver in some absolute sense hangs in the air above the transaction. And to be certain, it is a transaction. As in the exchange of those potlatch gifts, the giver expects something in return for her gift even if it is only a mumbled thank you. Trying to help people in another culture adds a level of complexity to the exchange because not every culture values the same things. I didnt understand how the help offered by colonizers, missionaries, and nations that preceded me cast a long shadow over all attempts at assistance.

I went to Bolivia assuming I would have connections with Indigenous Bolivians because of our shared identity as Indigenous people. All those powwow planning meetings in college with my Paiute and Yakima classmates included disagreements over everything from who should carry the flags for grand entry to the type of frybread we would serve, but we accepted that we shared a connection. In Bolivia, I learned about the similarities in the history and experiences of Indigenous people in North and South America. In South America, the Spanish launched a brutal campaign to subjugate and eradicate the Indigenous people in what would become Bolivia. On the West Coast of North America, the Spanish established a mission system with the intention of subjugating and eradicating the Indigenous people in what would become California.