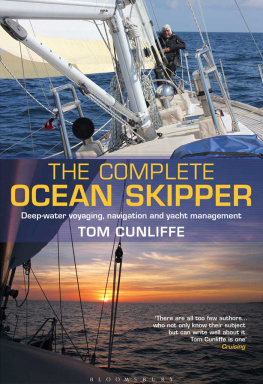

MAKING LANDFALL AT AN ANGLE GIVES YOU MORE OPTIONS IF YOU FIND UNEXPECTED SHALLOWS, ALTHOUGH THE RADIO MAST ON THIS HEADLAND MAKES IDENTIFICATION CLEAR.

There are many situations where you come from seaward to make a landfall. It could be after a long open sea passage, it could be coming into an anchorage for lunch or it could be making for harbour. These will be the times when you move from deep water into the shallows and where, if you keep going blindly on, you will hit something or run aground. With GPS operating and the depth sounder running, you should be in control of the situation and the landfall will go according to plan. However, poor visibility or uncertain chart information can raise the risk levels of making a landfall, and things can get critical very quickly.

One way to reduce the risk is to choose the point of landfall carefully. Even if its not your final destination, you can make sure you avoid any off-lying dangers and find a point where a gradual shoaling will give you early warning of arrival.

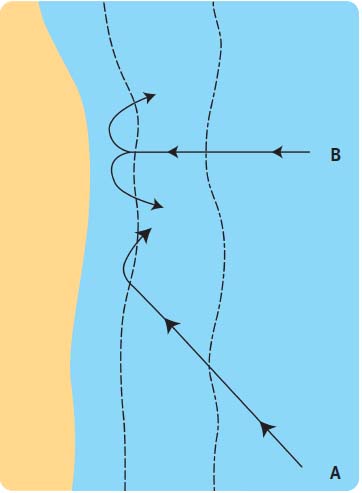

Another way to reduce the risk is to vary the angle of approach. If you are heading straight in towards land and the unexpected happens, you have two options about which way to turn to get out of danger: left or right. There will probably be little or no indication about which is the best way to turn when the sounder shows sudden shoaling or other dangers loom up ahead. But whichever way you decide to go, you will need to make a 180 degree turn before you start to head towards safety.

You can take a lot of the guesswork out of the situation if you approach the land at an angle of around 45 degrees. Not only will this slow down your approach into the shallows and give you more warning of hazards, it will also remove the dilemma about which way to turn if you encounter a problem. If you adopt this angled approach not only is there only one logical way to turn but the turn itself will also be less acute, and you will be able to resolve the situation a lot quicker and a lot more safely.

If you are making a landfall like this under sail, the wind direction will have a considerable bearing on your actions. It may limit your angle of approach in the first place: you dont want to be close hauled and have to turn up into wind to get out of trouble, as you could lose steerageway at a critical moment. Close-hauled, you will probably have to turn through at least 90 degrees to start moving away from danger, so consider finding an angle of approach that allows you to change direction both quickly and safely. Under both power and sail, if you have a bow thruster, have this switched on ready for use to speed up the turn.

WHEN MAKING A LANDFALL IN POOR VISIBILITY IT IS BETTER TO APPROACH AT THE ANGLE SHOWN IN A. APPROACHING THE COAST DIRECTLY AS IN B MEANS HAVING TO TURN THROUGH A GREATER ANGLE IF YOU DETECT SUDDEN SHOALING AND YOU WONT NECESSARILY KNOW WHICH IS THE SAFEST WAY TO TURN.

WHEN YOU PLAN YOUR ROUTE TO PASS CLOSE TO A BUOY IT NOT ONLY SHORTENS THE VISUAL DISTANCE BETWEEN MARKS, IT CAN ALSO GIVE YOU A CHECK ON WHAT THE TIDE IS DOING.

Normally when you want to travel between two points you will draw a direct line on the chart to give the shortest distance. However, when you plot this shortest route it may not be ideal from a navigation point of view, so you should look at other possibilities before finalising it. You also need to check the route to ensure that you arent proposing something that takes you over or close to navigation hazards but there can also be other considerations to take into account.

If you are navigating using GPS position fixing on an electronic chart, the direct route should work because you are getting constant fixes along the way. However, it is always prudent to check your position using sources other than GPS. You can easily do this by making minor modifications to your route. Look along your proposed route and seek out navigation marks (such as buoys marking isolated shoals or rocks) that lie on either side of it. It may be sufficient to just see them in the distance but in poor visibility you might want to deviate from the straight-line course to get a positive fix.

If you do decide to deviate from the course in order to pass closer to these marks you obviously need to pass on the safe side of the buoy, away from the danger that they mark. If you follow this method of visual checks, you could end up with something of a zigzag course, but unless you have made major deviations the actual distance is not likely to be much greater than the straight line.

The benefit of adopting this tactic is that you will get regular visual checks on your position as you go along. These not only offer reassurance but also provide a check on the performance of the GPS.

Whilst GPS is very reliable and will rarely let you down, one of the golden rules of safe navigation is to check your position from at least two independent sources. Making regular visual checks does this in a very positive way and it also allows you to see what the tide is doing when you pass the buoy.

DEVIATING TO GET A FIX WHEN MAKING A LANDFALL CAN BE VERY HELPFUL IN FOG.

If you are crossing a bay and going into head seas, the direct route from headland to headland may not be the quickest. It can often pay to deviate into the bay and follow the coastline around to the next headland (provided of course that there are no navigation hazards that could cause a danger on the way). The tactics will differ between powerboats and sailboats but there are benefits for both.

There are several advantages to taking the longer route. Firstly, by altering course into the bay you will be putting the wind on the bow instead of directly ahead. In a powerboat, this should give you a more comfortable ride. Secondly, as you head into the bay you will start to receive protection from the worst of the seas by the headland that lies on the other side. This means that when you have to turn along the coastline and head into the wind, you should find better sea conditions and get a better ride, allowing an increase in speed.

Conditions should continue to improve as you approach the next headland, allowing a faster and smoother ride. By doing this, the trip around the bay should be quicker than the trip directly across, and you will get a more comfortable ride into the bargain. You will still have to face the head seas when you reach the headland but you can often find a patch of relatively smooth water close in under the headland where the tides are weaker. Check the chart closely before going close around the headland to make sure there are no rocks or shallows close in that could cause danger. Also be aware of any tide races that might exist, where both the tides and the wind can be stronger.

On a sailboat, when there is a headwind from headland to headland, you will be faced with the option of tacking into the bay or tacking out to seaward. Whilst the inshore option may look attractive because it takes you out of the rough seas and the possibly stronger adverse tide, you may find that the wind is heading you along the coastline as you come out of the bay. If this happens, you will need to tack out again at a fairly early stage in order to round the headland safely.

Next page