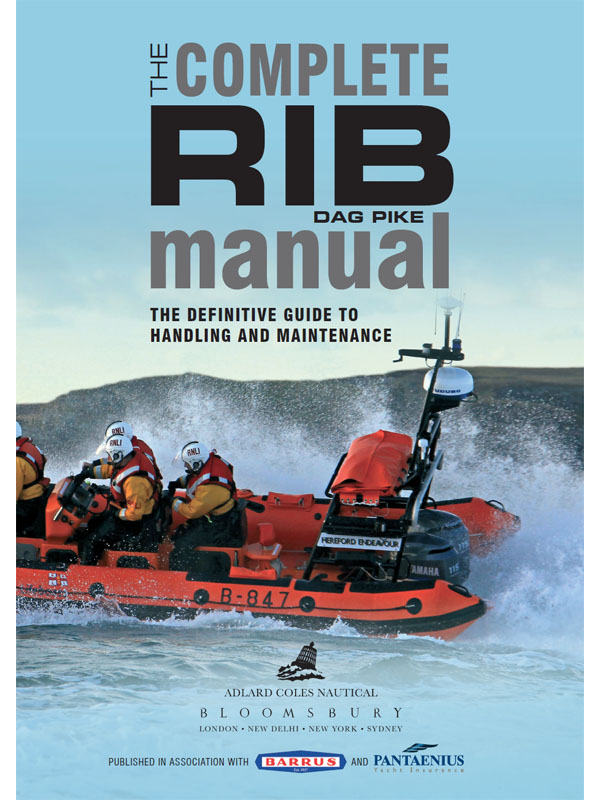

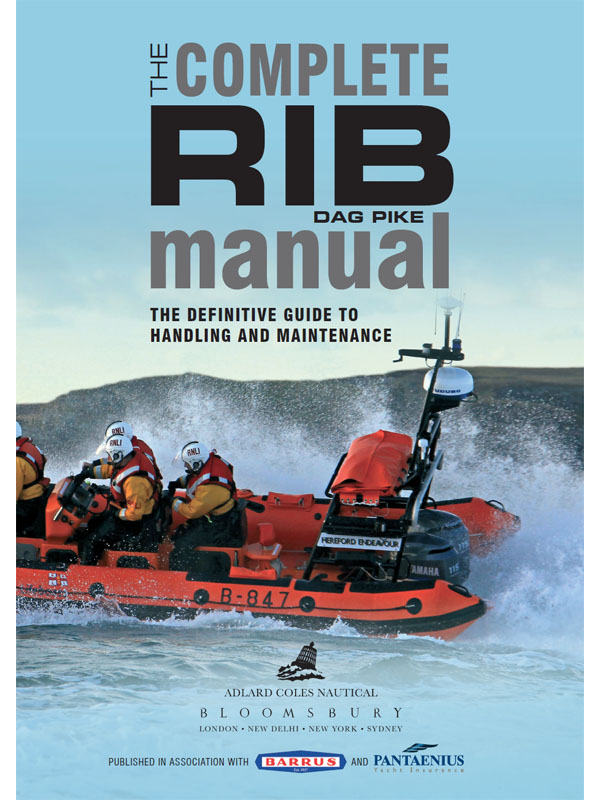

The rise of the Rigid Inflatable Boat (RIB) has been one of the most dramatic developments to take place in recent boating history. Most changes in the boating world take place in a slow, step-by-step way, but within just a few years the RIB had taken it by storm. What makes it more amazing is that the RIB started life as a rescue boat in the commercial sector, and then went on to embrace every part of the market.

The RIB was developed from the inflatable boat, so its arrival was not quite a sudden Eureka moment. However, the inflatable was developed primarily as a practical, portable boat that could be deflated and folded up. The RIB turned that idea on its head and replaced it with a less portable concept that embraced most of the good features of the inflatable and the best of the modern sports boat. Add a few bells and whistles such as the saddle seat, and the RIB became what was probably the most seaworthy and practical boat for its size anywhere in the world.

You might expect that would be enough to ensure its success in the commercial and military sectors but what no one expected was the way in which the RIB was adopted in the leisure market. Perhaps this was a reflection on the design excesses of some of the sports boats at the time, maybe there was a latent demand for a boat that was both practical and safe, or maybe people were just excited by something different that they could use as a fun boat. Whatever the reason, the boating public took to the RIB like a duck takes to water and the rest is history.

It is interesting to note that it was also the leisure market that started the trend towards larger RIBs. So many people, including me, thought that the RIB was only viable in smaller sizes, where its extraordinary capabilities really stood out. In larger sizes the advantages were not so apparent (which was not a problem for leisure users, but was for the commercial/military sector). But as soon as it became clear that the RIB was the perfect boat design when you needed to go alongside other vessels at sea, and had an authoritative appearance, then first the military and rescue people adopted the concept, and now most commercial operators use all sizes of RIB as their boat of choice.

All of this is despite the fact that a RIB is more expensive to buy and maintain than a matching hard hull, so the benefits must outweigh the extra cost. I do wonder how many people actually try to quantify this, but the RIB has now become the standard by which other boats are judged.

Appearance has become a very important factor in RIB design in the leisure, commercial and military sectors, and it is starting to compromise other aspects of the design. To make them look good, the tubes are inflated so hard that they bounce rather than absorb impact shock loadings. The result is a harsh ride, to the point where many operators now demand the fitting of sprung seating to protect their crews. This in turn can add weight to the boat in the wrong place, making the ride even livelier. Reducing tube pressure is essential to a smooth ride, but sensitive driving also helps. Hull design is also a major contributory factor and the lessons we learnt from the early days of RIBs are being largely ignored in the search for performance and style. We seem to have entered a vicious circle of development that does not have an easy solution, and need to go back to the basics of RIB design to find answers to the various problems now facing RIB operators.

Despite this, RIBs are now so good that crews tend to drive them to the limits rather that nursing them through the waves. There is sometimes a macho culture amongst RIB drivers that can lead to less than skilful driving. RIB crews have now become the weak point, rather than the boat and its engine: this is a tribute to modern RIB designers and builders, but does show that the time has come for a major rethink about RIB design and driving.

Today the RIB is everywhere and there are probably more RIBs being built than any other category of boat. You can see them in every harbour, where they are used as yacht tenders, stand-alone sports boats, harbour patrol boats and serious cruising boats. Thrill-ride operations almost invariably use RIBs as their go anywhere boats and in nearly every country around the world the military now operates RIBs.

I am proud to have played a small part in the development of the RIB, even if was mainly to show what didnt work. I am proud of the way that the RIB has advanced boat design and development into a whole new world of capability. After 50 years of existence, the RIB is set for world domination, and its place in maritime history is now assured hopefully for all the right reasons.

The RNLI inflatable rescue boat from which the RIB developed

THE FIRST STEPS on the road to developing rigid inflatable boats (RIBs) were taken when we were trying to solve a problem. During the 1960s there was a growing number of casualties around Britains coasts involving small boats, surfers and swimmers, and the large all-weather lifeboats were not well-suited to rescue work. The lifeboat society in France (Societ Nationale de Sauvetage en Mer) had introduced the flat-bottomed inflatable boat as a small rescue craft that could operate off open beaches. The French had a fleet of 5-metre Zodiac inflatables and a year or two later the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) introduced its own inflatables based on that Zodiac design.

These inflatable rescue boats had a tough life operating from open beaches

IMPROVING THE INFLATABLE

The 5-metre outboard powered boats did a wonderful job of inshore rescue work and were welcomed by the traditional lifeboat crews as a supplement to their all-weather, but slow, traditional lifeboats. However, the virtually flat fabric bottom meant the crews were in for a harsh ride through wave impact, even though the inflatable structure of the boat absorbed some of the shocks. Furthermore, the shape of the hull made them susceptible to a high level of wear and tear, particularly when they were launched and recovered from open beaches. However, their flexible nature and ability to absorb some of the wave impact was noted, plus the inflatable tube also made a good built-in fender for boats used for rescue work at sea.

I got involved with these rescue boats when I joined the RNLI as an Inspector of Lifeboats in 1962. Initially I introduced the craft to new lifeboat stations and trained crews to use them, before managing all maintenance and development of the inshore lifeboat fleet.

The RNLI built up a fleet of over 100 inflatable inshore lifeboats. Since many of the new lifeboat stations were operating from open beaches, the boats were being dragged across rough sand and shingle during launch and recovery operations. This was causing the bottom fabric to wear out quickly, particularly in the area around the wooden transom, and it was becoming a major maintenance headache. In an attempt to overcome it, we cut out the rear section of the floor fabric (about 1.5m) and replaced it with a piece of flat plywood braced rigidly to the transom. The plywood was able to stand up to the harsh conditions and as a bonus it also improved the boats performance by creating a hard planing surface. This semi-RIB solution also allowed the boat to be deflated and rolled up for easy transport when a replacement had to be sent to a lifeboat station.

Next page