THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO

SAILING & SEAMANSHIP

THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO

SAILING & SEAMANSHIP

Twain Braden

Illustrations by

Sam Manning

Skyhorse Publishing

Copyright 2013 by Twain Braden

Illustrations Sam Manning

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file

ISBN: 978-1-61608-246-8

Printed in China

TABLE OF CONTENTS

This book is dedicated to the memory

of my father, Tom Braden,

not much of a sailor but a hell of a guy.

TB

INTRODUCTION

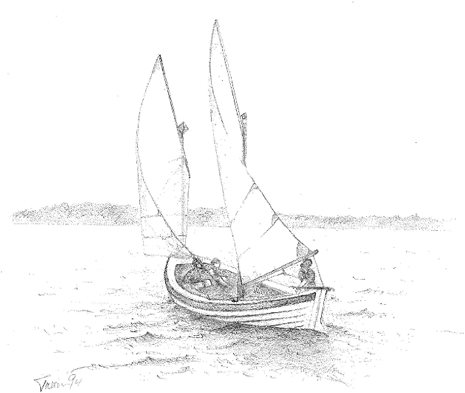

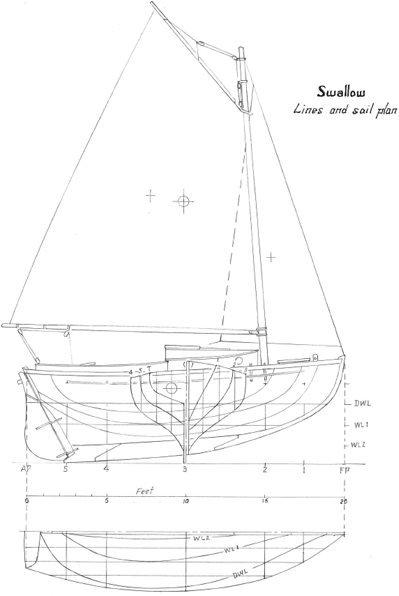

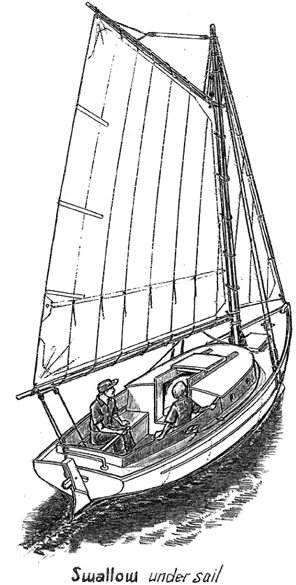

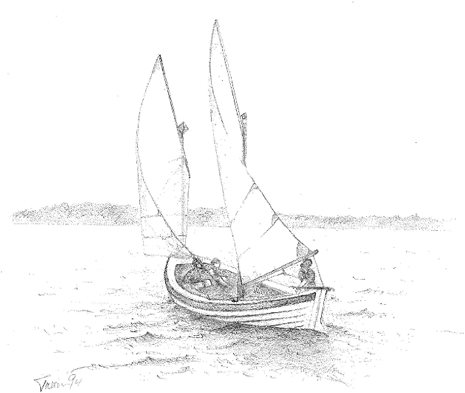

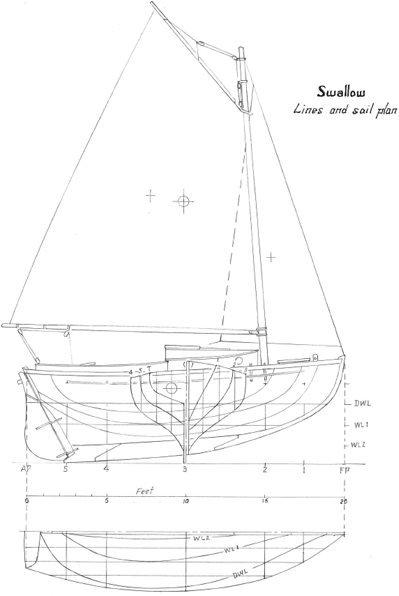

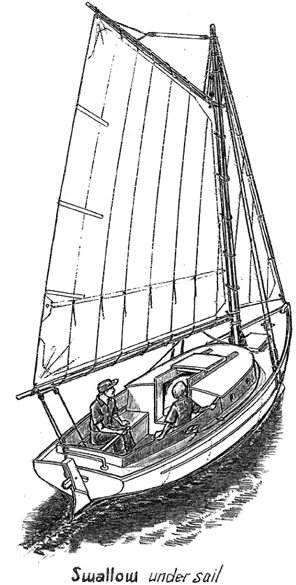

T he stories and examples detailed here take place on a boat that does not exist. Rather, its design was hatched by Sam Manning and me to best illustrate the approach to sailing that we offer in this book. This hypothetical boat is a twenty-foot, full-keel sloop with a jib and mainsail. The vessel has an inboard diesel engine. The hull construction doesn't matter for our purposes, but I often discuss (and Sam has drawn) a boat made of wood because of the universality of the parts of a boat made of wood, such as the frames, stem, transom, and planking. The scenes that these terms illustrate are easily translated to a boat with a fiberglass hull. And while many of the drawings show a gaff riglargely because of partiality on our part having to do with its attractiveness and joy of handlingthe same principles of boat handling apply to a Marconi-rigged boat. We will call it Swallow, for reasons explained below.

The approach I take to learning to sail and to becoming expert in handling a small boat at sea represents a certain philosophyan amalgamation of my own and that of countless others I've sailed with over the years. This is not the only way to learn to sail. It's simply one way of many by which a novice can approach sailing. But it's one gleaned from years of experience teaching people, not so much how to sail as much as how to handle a boat under sail. There's a big difference. Sailing itself is simply the mechanics of how a boat works under sail. Handling a boat under sail, however, is about seamanship itself, from the rigging to the hull; from the dock to the island; and from the anchorage home againand everything in between.

This is not a comprehensive treatise on sailing. It's a purposefully slim volume that is intended to be accessible to the lay reader who simply wants an approximation of the concepts of sailingroughly 90 percent of what you need to know to get started. The subject is simply too vast and is available elsewhere in more specific bookswhether on navigation, anchoring, or rough-weather boat handling. The other elements of sailing, which are really the greatest parts, will be acquired through experience. A little background knowledge is helpful, of course, but really there's nothing more valuable and enjoyable than jumping into a small boat, getting underway, and learning (carefully!) as you go.

Some time ago I went sailing with Scottish adventurer Sir Chay Blyth in Bostons outer harbor. As a magazine editor at the time, I was invited with other media types to experience his nimble vessels, the fleet that he used for his so-called Challenge Business, so that we might be charmed enough by their handling that we would be inclined to write favorably about them. The boats were fine enough, about seventy feet overall, and proved fast and sturdy as their young, professional Australo-British crew put them through their paces in the summer breezes. But what was most interesting to me was the story Sir Chay told me as we tacked our way eastward out of the harbor while standing on the foredeck.

Sir Chay is a small man, about five-and-a-half feet tall, but his stature grew with his energy as the story unfolded, until he seemed a giant as he waved his arms emphatically, his Scottish brogue punctuating each salient point with the air of an ancient Highland giant.

He told me that when he had set about planning to build a fleet of boats to sail around the world with paying passengers, he hired his long-time designer friend Andrew Roberts. He asked Roberts to come up with a concept for a vessel that would maximize sea-kindliness and accommodate a sizeable number of paying passengers so that voyages could generate a profit, but be inexpensive enough to build because they needed no customization. In short, every part should be off-the-shelf to minimize cost yet be assembled in such a way as to maximize overall size so that the largest number of paying passengers could be accommodated.

He asked me:

"If you were to build such a fleet of vessels that were to carry passengers around the world on a yacht race, where would you start? How big would the boat be? How many passengers?"

"I don't know," I mumbled vaguely, "perhaps for a crew often? Start with ten berths?" It seemed like a nice even number.

"Why ten?" he asked. "Why not elevenor nine?"

I had no answer. And he smiled rather like he knew the joke was on me.

He then described how this question had plagued him and the designer for months. They needed some benchmark that would dictate the starting point and therefore the rest of the design. In this country, people wanting to sail boats for profit have such a benchmark. Six passengers are all you can carry if you don't want the Coast Guard spending too much time asking questions about safety gear. You can have an "uninspected passenger vessel" carry six paying passengers, and they'll leave you alone so long as you provide lifejackets for all. As a result, many low-budget commercial outfits choose this number to design their business around. The number six dictates the highest number of berths (plus one or two crew), which dictates the overall size of the boat. One much smaller and you can't maximize profit; one much larger and you're wasting money. But there are no such restrictions in other countries, and, besides, Blyth was aiming higher than the U.S. Coast Guard's standards anyway.

Finally, Blyth received a call from Roberts in the middle of the night. The designer was in a fit of passion, in the throes of a kind of Archimedes'-eureka-by-Jove euphoria, that would yield the key to how to proceed with the design.

"It was the main sheet winch," Sir Chay told me. "That was the answer."

If you took the largest main sheet winch that you could buy off the shelf, its size would dictate the breaking strength of the main sheet, which would then dictate the sail area of the mainsail, which would, in turn, dictate the overall size of the rig. And the size of the rig would dictate the volume of the hull and, therefore, the number of people you could fit in the hull. And so you had a vessel that ultimately was designed around the largest production winch available. This kept costs down, since none of the parts would require any custom labor; the whole boat could be built with production hardware.