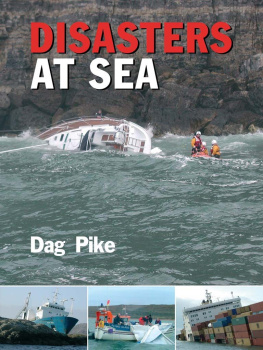

Introduction

Disaster is a constant threat when you go to sea. Most of the time everything works and a voyage goes smoothly. But dangers are all around, and the consequences of getting it wrong can be very serious. The uncaring line between survival and calamity can often be very fine. Even modern technology holds no guarantee of security, and most sailors have tales to tell of misfortune or near-tragedy during their time at sea.

When man first started exploring the oceans, there was every opportunity for disaster. Craft were solely at the mercy of the wind. Charts were rudimentary or non-existent the mere thought of making a landfall without them is completely beyond modern navigators. Being at sea without a weather forecast, or relying on your own weather skills, is also alien to todays sailor. But those pioneering seafarers made it work, or at least the ones who survived did and it is only the successful ones we tend to hear about. There were countless poor souls that never made it, lost in circumstances never recorded.

Electronic wizardry

Today we go to sea with the latest technology at our fingertips. We have reasonably accurate weather forecasts for up to five days ahead. The charts we use are accurate and up-to-date. We carry electronic wizardry that plots our course and detects other vessels seemingly miraculously.

Yet still disaster strikes with uncomfortable regularity. You only have to look at the casualty pages of Lloyds List, the shipping newspaper, to realise that major incidents occur on an almost daily basis. These are so many, they often fill a whole page and those are only the entries for commercial shipping. Fishing vessels are equally vulnerable. Yachts too have their fair share of mishaps. So if our modern world is so risk-averse, how are such casualties tolerated and why do they happen?

In theory, there is no technical reason why disasters should occur. Modern ships and small craft are well built. They have enough position information to locate themselves anywhere in the world to within a few metres. They have very clever radar to help avoid other vessels. They have communications systems for keeping up to date with the latest weather and navigation information. On the face of it, there is no excuse for getting it wrong.

Undoubtedly, the weakest link in all of this technology is the human element. Just as human ingenuity coordinates all the different workings of a vessel and makes the decisions, so human frailty finds fallibilities, defeating technology at a stroke.

Human error

It is reckoned that up to 80% of all casualties are caused by human error. From personal experience, I would actually put that closer to 100%. The 80% relates to cases with direct evidence of human cause not recognising a collision risk until it is too late, or failing to heed deteriorating weather conditions. Navigation mistakes also fall into this category. So do the not so obvious accidents of engine failure or hull breakage. Somewhere the designer got his figures wrong, or the maintenance person did not do his job properly. All of which means that whoever was assessing the risks made a wrong call and misjudged them. In my eyes these are all human error. And in nearly every case, a disaster at sea can be traced directly or indirectly to human failings of one sort or another.

Both shipping and yachting are unique in the relaxed way that they are regulated. By comparison, all other forms of transport have pretty strict control. Aircraft, for instance, are guided along routes that are dictated from the ground. Collision avoidance is not up to pilots, but handled by ground control and most of the time, it works. Trains are kept on the straight and narrow by the rails and a signalling system. Even road traffic is strictly controlled when compared to shipping.

Ships and yachts, on the other hand, are pretty much free to roam the oceans as they please. The only significant form of control is in the Vessel Separation Systems that are used in narrow seaways and some harbour approaches. Even with these, it is the ships navigator who determines the point and method of entry, the course to be followed and the collision avoidance tactics. The actual level of control is minimal and all safety measures depend totally on the navigator. It is hardly surprising, then, that some navigators on either ships or boats find they cannot cope, nudging misfortune nearer. Add in substandard ships, poorly equipped yachts, people with little or no qualification or ability, and you have a recipe for disaster.

Testing ships

On the design and construction side of the industry, I find it quite incredible that nearly every ship is built as a one-off. There have been some attempts over the years to build ships to standard designs, but even these make little or no attempt at prototype testing. The yacht and powerboat industry is closer to standardisation because each popular design is eventually built in big numbers. Though even then, the principle of developing a prototype first and putting it through a series of exhaustive trials and tests at sea is not even considered.

The only time a ship or a small craft is tested in rough seas is when the owner or the skipper runs it into bad weather. Compare this to the automobile and aircraft industries, where prototype testing takes months and a new design is subjected to near-destruction testing to eliminate problems before entering service.

Alongside such levels of integrity, marine development is in the dark ages. True, the classification societies do their bit by establishing standards that help eliminate failure in construction. But none of these covers the same vessels in their behaviour at sea. Rough sea experience can certainly show what works and what doesnt in terms of hull design. Even so, I have come across some very questionable designs during my experience of powerboat testing.

Lifeboats that go out to rescue others in the worst possible conditions are one of the few exceptions to this pattern, and their prototypes are thoroughly tested in the worst conditions. When working for the RNLI I had a simple brief when evaluating new designs: Go out in the worst conditions you can find, and see what happens.

You can imagine the hazards that lack of standardisation throws up. Picture a ship that leaves Rotterdam with a new crew, entirely green to her. With luck they might have 24 hours to become familiar with her; quite a challenge with no standardisation in bridge equipment or its layout, or even in the control systems, radar, or the electronic charts carried.

The crew are on their own

The pilot might take the ship out to sea successfully, but after that the crew are on their own. They are now in at the deep end, in some of the busiest waters in the world. It could be dark too, an added trial when using new equipment and learning how it works, at the same time as navigating safely through ships coming at them from all directions. Is it any wonder that accidents happen as often as they do?

Believe it or not, yacht and fishing boat skippers have the advantage here. They tend to use the same vessel and equipment whenever they go to sea, so they are more likely to be familiar with it. Yachtsmen, though, may have a considerable gap between periods at sea, so they may have to go through the learning process again.

You have to wonder whether accidents resulting from this kind of scenario should really be classed as human error. On the face of it, the crew might be negligent or incompetent. But is it fair to blame the operator who has to use equipment in this way? The operator (and in most cases that means the captain or the skipper, because that is where the buck stops) has to make the best of the circumstances he is presented with.

Next page