2015 by Smithsonian Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

This book may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write: Special Markets Department, Smithsonian Books, P. O. Box 37012, MRC 513, Washington, DC 20013

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Production Editor: Christina Wiginton

Edited by Gregory McNamee

Hardcover designed by Ashley Hornish

Image Research by Thomas Paone

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data TK

eISBN: 978-1-58834-492-2

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-58834-491-5

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these images individually, or maintain a file of addresses for sources.

Visit the Time and Navigation web site: timeandnavigation.si.edu

www.SmithsonianBooks.com

v3.1

CONTENTS

TIME and PLACE Connection

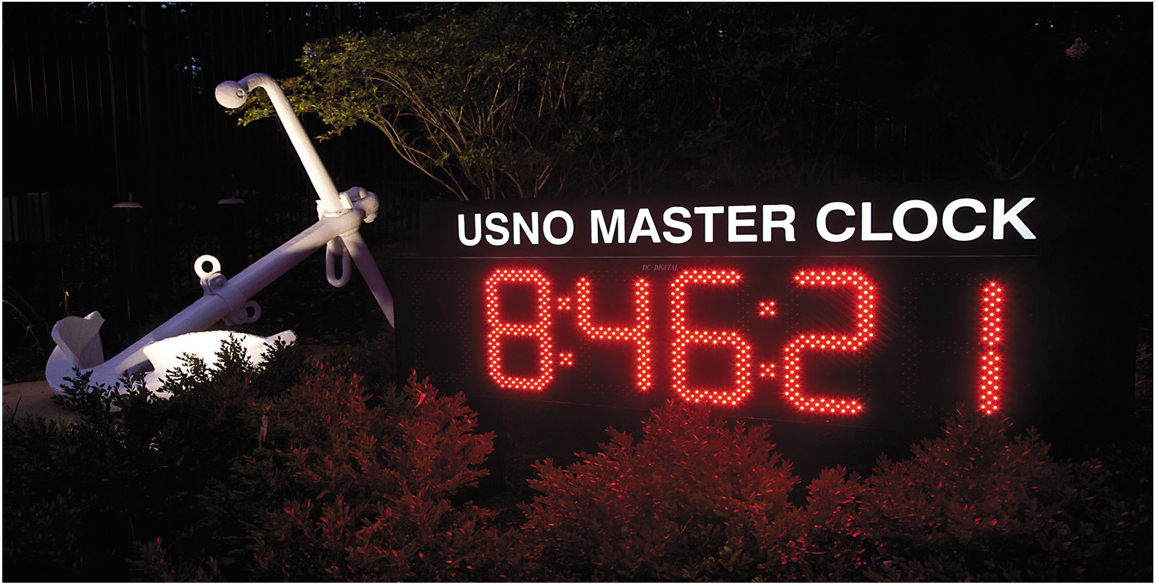

Time display at the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C.

W e are all navigators. To find our way from here to there, we often look for landmarks or use maps. Today, we use smartphones and GPS to get around. But navigating has not always been effortless. Across the centuries, as people crafted new methods by which to navigate, they faced technical complexities, harsh environments, and personal peril. Voyagers often became lost, never to be found. Having a reliable way to navigate could mean the difference between life and death. The human need to travel and make connections across the world has inspired, among many other things, the art and science of navigation.

Getting from one place to another involves more than just knowing where . We also need to know when . If we want to know where we are, we need a reliable clock.

This surprising connection between time and place has been crucial for centuries. About 250 years ago, mariners first used mechanical clocks to navigate the oceans. Today we locate ourselves on the globe with synchronized atomic clocks in orbiting satellites. Among the many challenges facing navigation from then to now, one stands out: keeping accurate time. Time and place are connected in ways that most people do not realize in their daily lives, and this connection has been an essential element in the development of global commerce and modern society.

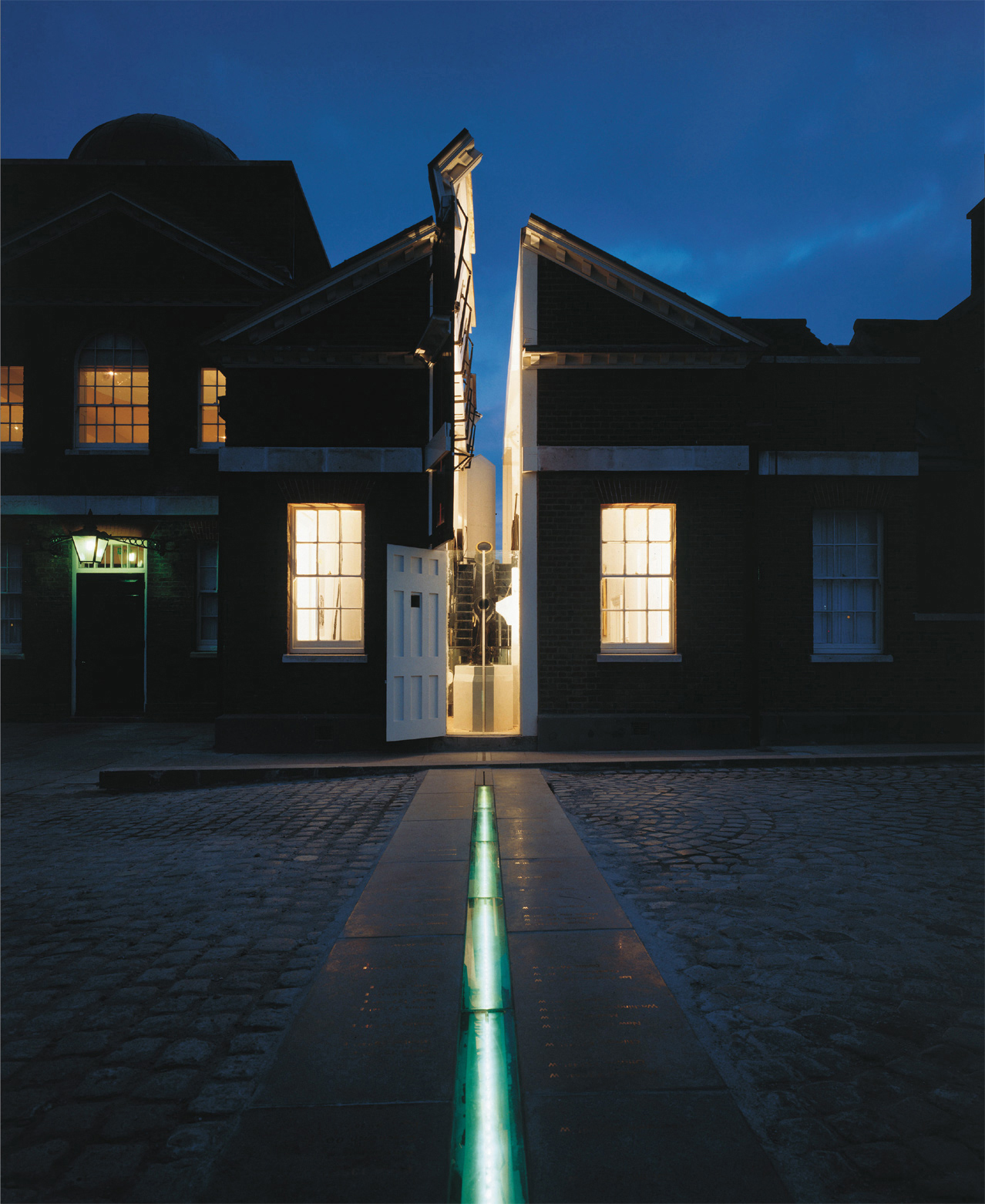

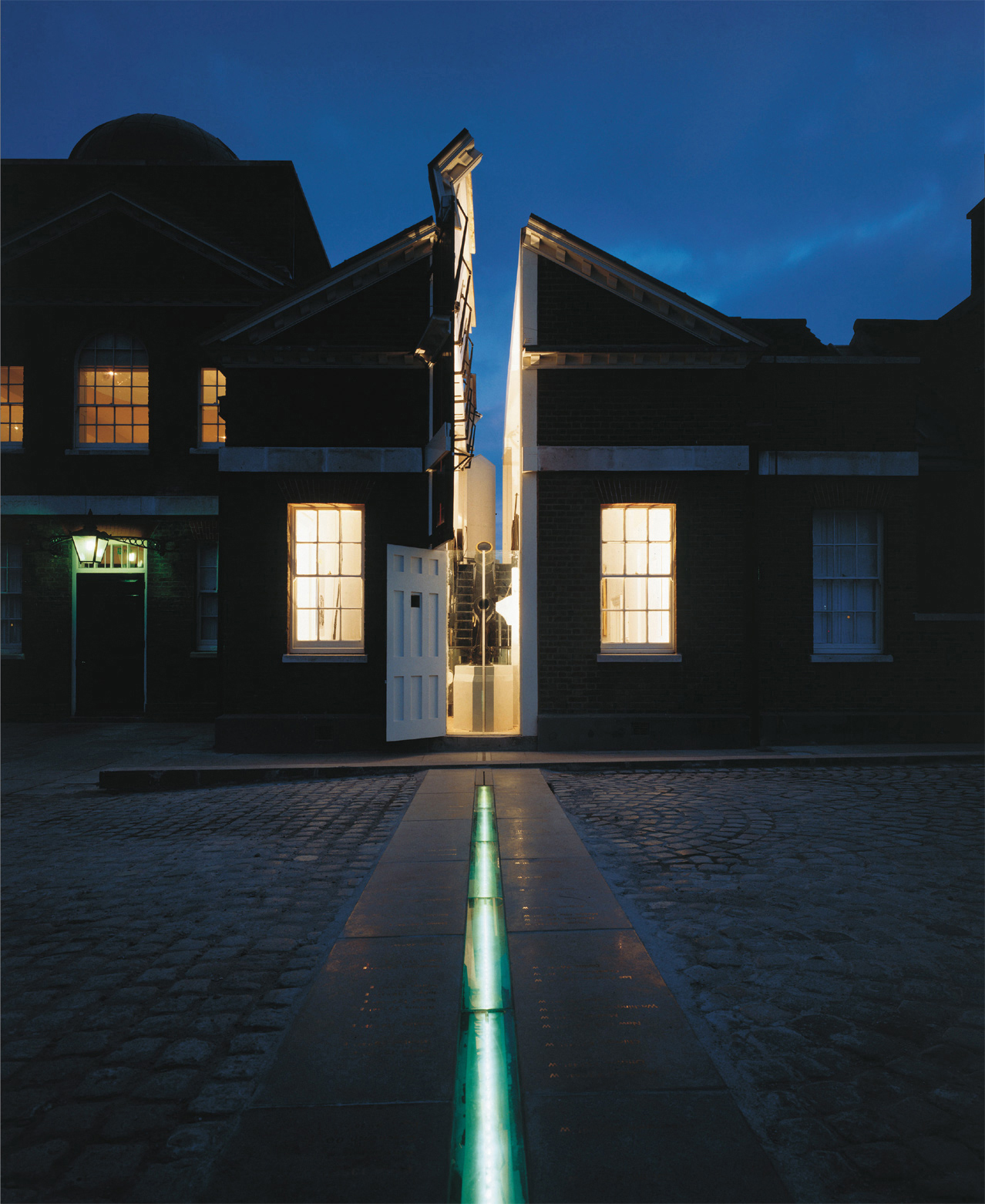

There is no better place on Earth for understanding the connections between time and place than the courtyard of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England. On this spot overlooking the city of London, those connections, first established generations ago, endure to this day on a global scale. Visitors can straddle a brass line in the courtyard corresponding to zero degrees longitude. This is the line from which all the other lines of longitude are based, reaching all the way around the globe. Greenwich reminds us that the oldest clock is Earth itself, and the oldest means of keeping time came from observing changes in the sky. Some of the earliest forms of navigation were based on the same principles. Prominent clocks at Greenwich and other observatories count the hours, minutes, and secondsonce determined with an astronomers eye on a telescope in a nearby dome, now transmitted from a physicists atomic clock in a laboratory.

Prime Meridian line at Royal Greenwich Observatory near London.

Sundial in the Smithsonians Enid Haupt Garden made by William David Todd for the latitude of Washington, D.C.

Over the centuries, clocks changed from luxuries to necessities and from rarities to ever-present machines. They also became more accurate. Mechanical clocks, invented in Europe just before 1300, were the basic timekeeping instruments until the twentieth century, when quartz and atomic clocks were invented. Requirements for navigation often stimulated improvements in timekeeping. Roughly speaking, the more accurate the clock, the better the positioning: In the eighteenth century, accuracy was measured in nautical miles, while in the twenty-first century it is measured in centimeters.

Information about time and place has played a crucial role in international politics. In their competition for empire, Western Europes maritime nations recognized early the importance of technical control of time as a means of determining place. Beginning at the end of the sixteenth century, their generous cash prizes stimulated solutions to the problem of measuring longitude at sea. The hot and cold wars of the twentieth century likewise spurred nations to fund new navigation solutions that could work at all times and in all conditions. Governments around the world continue to devote huge sums to develop and deploy space-based systems for providing regional- and global-scale navigation services.

In concert with all these developments, the role of the navigator has dramatically changed through history. In the past, navigators served as elite practitioners with specialized equipment and training. In recent years, professional navigators have almost entirely disappeared from many fields, replaced by black boxes receiving ground- and space-based signals. The widespread availability of navigation services from orbiting satellites, however, has made it simple for ordinary people to determine position and obtain updated digital maps. Navigation has become more of a global utility than a specialized art.

This book explores these themes through history in different environments. It offers an illustrated history of how scientists and explorers invented a style of navigationthe process of getting from here to therethat combined timekeepers with other instruments and techniques for wayfinding. It explores the changing role of the professional navigator, relates improvements in timekeeping to the demands of navigation, and reveals how and why national interests have stimulated improvements in navigation.

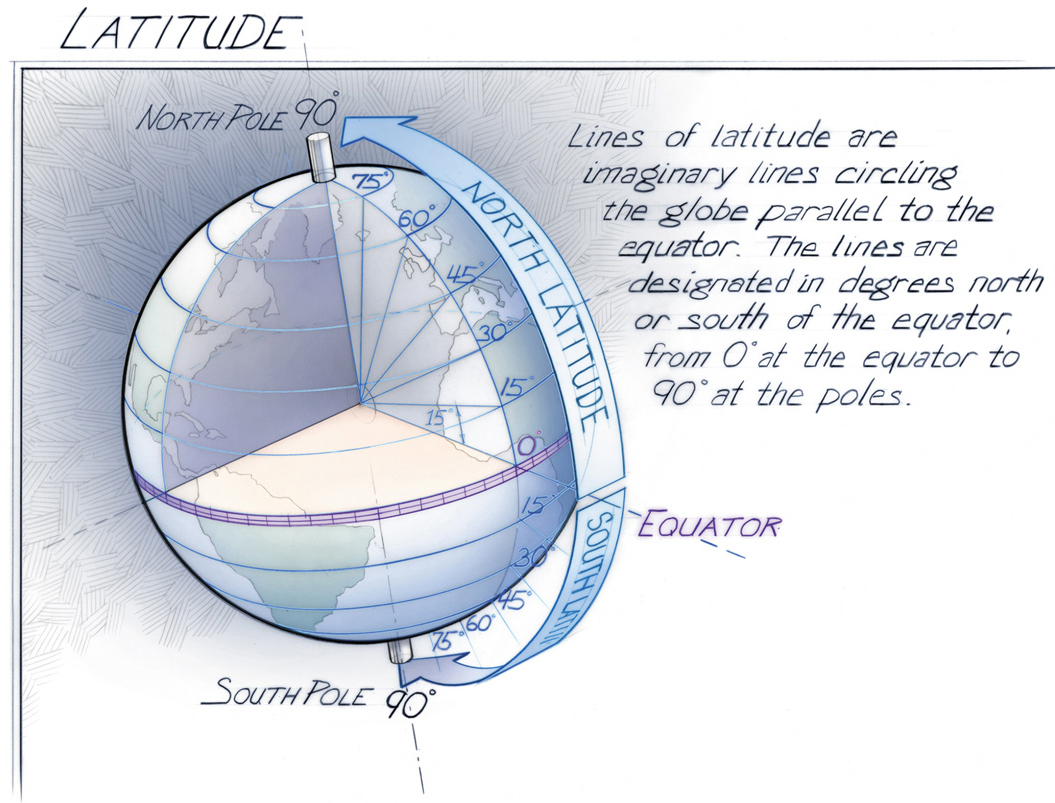

Lines of latitude have been used for thousands of years to define positions north and south, based on angles measured from the center of the earth. Lines of latitude circle the globe perpendicular to the axis of rotation.

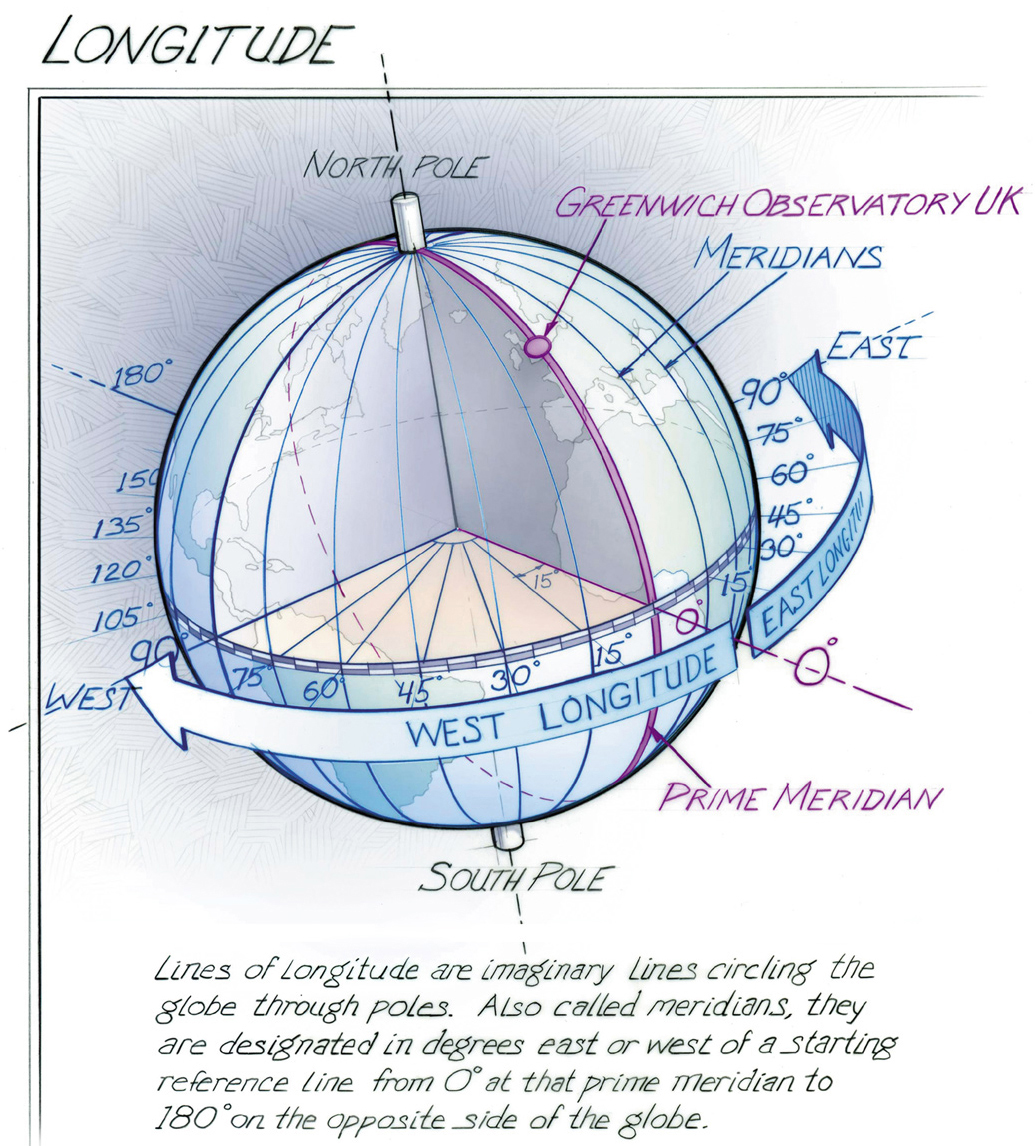

Lines of longitude, measuring position east or west, are designated in degrees east or west of a 0 line called a prime meridian. In contrast to latitude, the placement of the 0 longitude line is not determined by the orientation of Earths rotational axis. It could theoretically be placed anywhere east or west on the roughly spherical Earth. Greenwich became the most commonly used prime meridian, and eventually the international standard. Because Earth rotates 360 degrees around in twenty-four hours, or 15 degrees per hour, the sun appears to move in the sky by 15 degrees longitude every hour. This connection between time and place allows anyone to determine their longitude on Earthif they have an accurate time reference, that is.