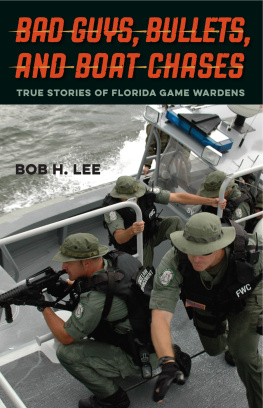

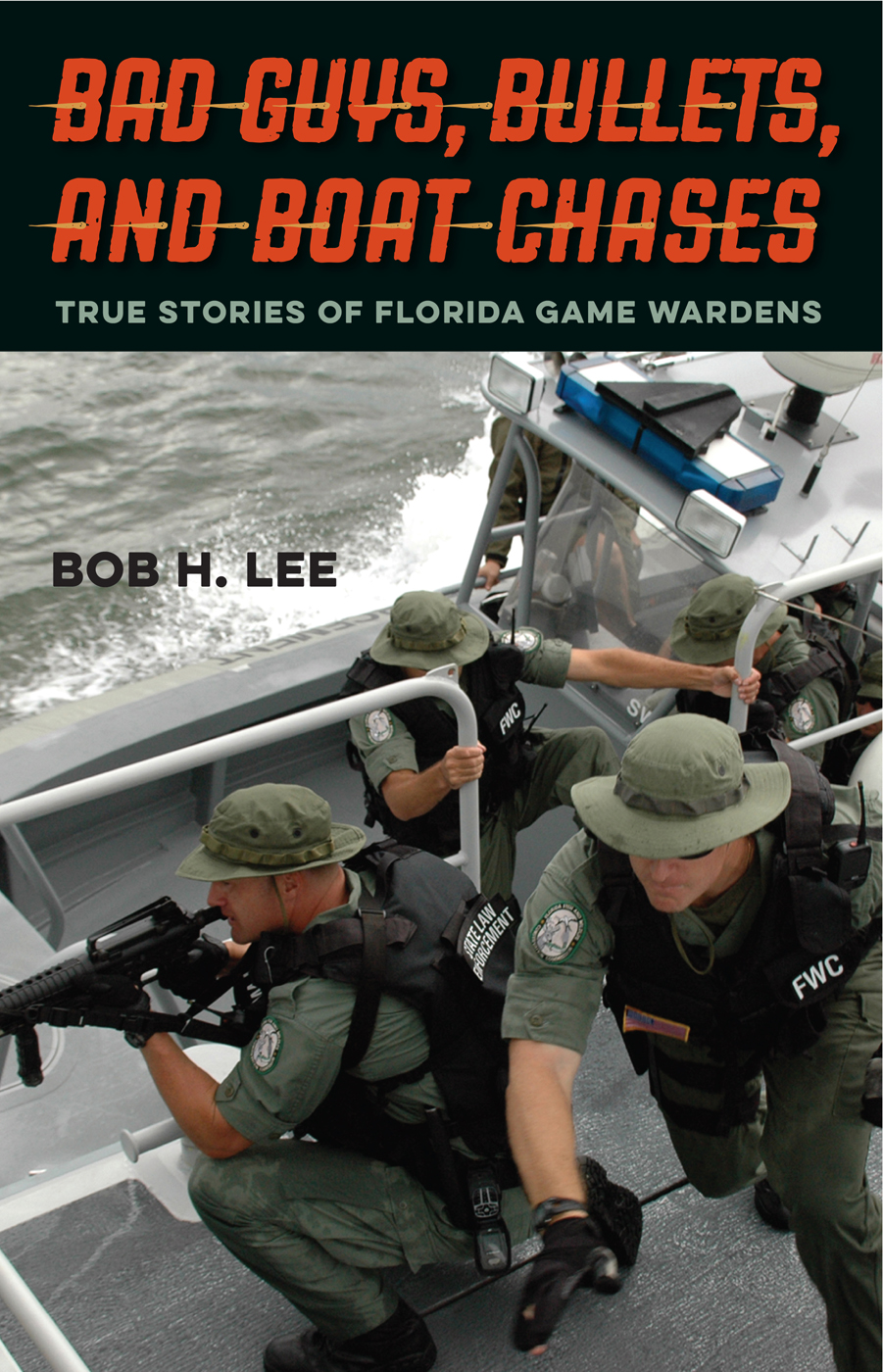

Bad Guys, Bullets, and Boat Chases

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF FLORIDA

Florida A&M University, Tallahassee

Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton

Florida Gulf Coast University, Ft. Myers

Florida International University, Miami

Florida State University, Tallahassee

New College of Florida, Sarasota

University of Central Florida, Orlando

University of Florida, Gainesville

University of North Florida, Jacksonville

University of South Florida, Tampa

University of West Florida, Pensacola

BAD GUYS, BULLETS, AND BOAT CHASES

TRUE STORIES OF FLORIDA GAME WARDENS

BOB H. LEE

University Press of Florida

Gainesville Tallahassee Tampa Boca Raton

Pensacola Orlando Miami Jacksonville Ft. Myers Sarasota

Copyright 2017 by Bob H. Lee

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America. This book is printed on Glatfelter Natures Book, a paper certified under the standards of the Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC). It is a recycled stock that contains 30 percent post-consumer waste and is acid free.

Photographs have been reproduced by permission of John Delzell (page 43); Lance Ham (page 73); Donnie Hudson (pages 59, 77, 81, 85, 87, and 88); Gray Leonhard (page 2); Curtis Lucas (page 112); Dwain Mobley (page 188); Jon Proctor (page 4); Vann Streety (page 230); and Mike Thomas (pages 97 and 108).

This book may be available in an electronic edition.

22 21 20 19 18 17 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016948258

ISBN 978-0-8130-6244-0

The University Press of Florida is the scholarly publishing agency for the State University System of Florida, comprising Florida A&M University, Florida Atlantic University, Florida Gulf Coast University, Florida International University, Florida State University, New College of Florida, University of Central Florida, University of Florida, University of North Florida, University of South Florida, and University of West Florida.

| University Press of Florida 15 Northwest 15th Street Gainesville, FL 32611-2079 http://upress.ufl.edu |

To all Florida game wardens, before, now, and after

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

Many years ago, a young hippie gal sidled up to me in a convenience store. Clad in an ankle-length cotton skirt, barefoot, with a disheveled mop of waist-length blond hair, she fixed me with a glazed stare and asked, Who do you kill?

I thought Id have a little fun with her and replied in my best deadpan, We dont kill anyone unless they need killing.

But, why, she said, clearly not seeing the gallows humor in my remark, would you need to kill anyone if all you do is check fishing licenses?

Indeed.

There are times when a job description cannot be summed up in a fifteen-second sound bite. In this book, I aim to dispel the notion that game wardens are mere license checkers. Too many times in my thirty-year career as a conservation lawman have I been approached by folks who ask what it is that we do. Rarely would a city cop, sheriffs deputy, or state trooper be on the receiving end of that kind of question.

After an adrenaline-fueled, high-speed nighttime boat chase on the St. Johns River, I first came to realize why what we do is often not grasped by the general populace. It was during the fall of 1978, my first full year as a rookie game warden in northeast Florida. I was alone, without backup, stuck with a clunker radio whose dependability relied more on whimsy than sound construction.

The bad guys were running blacked-out and took it to another level of danger when they set a suicide course dead center into an unlit channel marker. With only a few feet to spare, they whipped around the rusty steel I-beam support and quickly swung back onto their original course. It was a trick, a setup, to sucker me into crashing. You see, my headlamp bulb had blown, and for the moment I was running with only the faint glow of starlight to guide me. I did take comfort, however, in the guttural roar emitted by my 200 HP Johnson. It held a distinct speed advantage over the 90 HP Mercury strapped to the transom of the fleeing boat. Not being able to see where I was going was my main problem of the moment.

The race continued across a shallow sandbar and into a narrow gap between two islands. I stood up and finally managed to wrestle a flashlight from the storage compartment beneath my seat. I accelerated, hopped over their trailing wake, and brought my patrol boat alongside. I thought wed both had enough fun for one night and decided to end the chase. I began crowding them, gunwale to gunwale, fiberglass crunching on fiberglass, gradually forcing them toward shore. In the bottom of their boat lay a pile of dead raccoons theyd taken illegally with a gun and light, my initial reason to attempt a stop.

The fleeing vessel was a sixteen-foot commercial fishing skiff occupied by a driver and a passenger who was seated amidships. Over the high-pitched whine of raging outboards, I shouted for the passenger to place his hands on top of his head. He complied, briefly. Then he reached for a 12-gauge pump shotgun lying next to him on a flat-board wooden seat. At the same time, I warily kept track of another gun, a shiny, big-barreled revolver sliding around on the blood-splattered deck near the drivers feet.

I was in a real pickle. I had to steer the boat with one hand and hold a flashlight in the other. I desperately needed a third hand to hold my service revolver.

Necessity, as they say, is the mother of invention.

I dropped my left elbow down onto the narrow rim of the steering wheel, using the soft indentation of my funny bone to guide it, while precariously holding the flashlight in my left hand. I drew my .357 Magnum Smith & Wesson with my right hand and placed the barrel right behind the passengers head as the two boats flew through the night. I shouted a stream of blue-black expletives that ended with his brains being blown out if he didnt comply.

Ignoring my commands, he dropped his hands toward the gun.

I began to take up slack on the trigger.

At two oclock in the morning, moisture in the form of dew coats every conceivable surface on the interior of a vessel. My left elbows purchase on the steering wheel was already tenuous when it slipped, casting the flashlight beam into the sky for just a millisecond, before I could illuminate the suspect again.

In that brief moment, hed managed to knock the gun into the drink. It was close. The closest I have ever come to shooting someone. But once I got them stopped, and secured the handgun and offenders, I took a moment to look around. There was no one there, just the twinkling of distant house lights from across the river at Browns Landing Boat Ramp, three miles south of Palatka. No newspaper reporters, television crews, or documentary filmmakers were present to witness the event. And that tends to be the way it is with a lot of game and fish cases: just you and the suspects alone in the dark, in the middle of nowhere, with some who would cheerfully kill you if they thought they could get away with it.

In the seventeen chapters chronicled in this book, I pull the curtain back to give a behind-the-scenes look at the often misunderstood world of conservation law enforcement. Four of the stories involve me, but the majority of the chapters are told in the third person and are based on dozens of recorded interviews with game wardens, as well as the examination of criminal case files that include written statements, digital recordings, videotaped interviews, video surveillance tapes, and newspaper articles. Whenever possible, I tried to visit the scene to get a feel for the terrain.

Next page