Table of Contents

A Life with Wildlife

From Princely India to the Present

M.K. RANJITSINH

Dedicated with affection,

To

Kalpana Kumari, Meenal and Radhika.

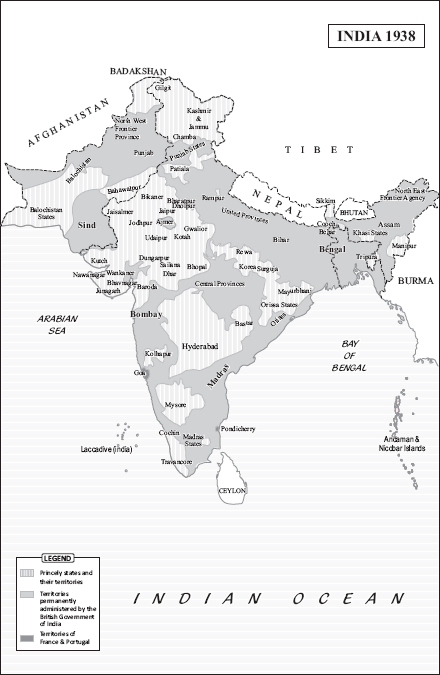

Cartographer: Nitendra B. Srivastava

Contents

B eing a student of history and fascinated by nature and wildlife since childhood, I have been attracted to legends and facts associating history, especially my family history, with wildlife. In circa 1077 CE, when Harpaldev Makwana the founder of our lineage lost his father and the kingdom of Kerantigarh, in modern-day southern Sindh, Pakistan, as a result of internecine warfare so common amongst Rajput princes, he sought refuge at the court of his cousin Karan Solanki, the ruler of Patan in north Gujarat. Patan today is famous for Rani-ni-vav, the most exquisitely carved step well in the world. In Mughal times it was famous as one of the principal sites for the capture of cheetah for royal sport (Habib 1982). Mirat-i-Ahmadi, a contemporary account of the Mughal period, goes on to say that the cheetah of this region (north Gujarat) is better and superior in relation to those available in other places (cited in Divyabhanusinh 1999). Why was it so? Was it because the cheetah here had to tackle the robust wild ass and the numerous nilgai, amongst the largest to be found in India? Wild asses ranged wide and have never been an object of the hunters pursuit, except for an interlude. Mughal emperor Babur (r. 152630 CE), an inveterate hunter who mentions all animals he killed and ate, from a rhinoceros to the quail, does not mention the wild ass (Babur Nama 1921). Yet his great-grandson Jahangir killed wild asses as far north as Lahore (Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri 1978). Slaying of the ghorkhar (wild ass) with swords from horseback was the privilege of the Persian nobility, in which Humayun partook whilst he sought refuge with the Shah of Persia after being ousted from India by Sher Shah Suri. When he returned to India and reclaimed his lost empire, he and his successors continued with this sport. India owes the origin of the Mughal style of painting and the adoption of Persian as the court language, which persisted till its substitution with English and contributed to the evolution of the Urdu language, to Humayuns exile in Persia. Can the beginning of the decline of the wild ass also be attributed to this Persian sojourn?

Legend has it that in Patan, Harpaldev married Goddess Shakti, after being subjected to a stern test, and that while she would appear before Harpaldev as a woman, to others she would appear to be lioness (Shukla, undated). Harpaldev acquired his own kingdom and established Patdi as his capital, at the edge of the Little Rann of Kutch. There, in the palace jharokha, or balcony, as Shakti sat combing her tresses, she saw an elephant that had escaped from the royal stables, bearing down upon her three children playing below. Shakti stretched her arms supernaturally, caught her children and lifted them to safety. Thereby the Makwanas came to be called Jhalas jhallya being the Gujarati word for caught. So my family name owes its origins to an elephant mad or in musth.

The tryst with animals continues. When Mohammad Begda, the ablest and the most ruthless of the sultans of Gujarat invaded northern Saurashtra, still referred to as Jhalawad, the Jhalas had to move westwards. In 1488 CE, whilst out hunting, Jhala ruler Rajodharjis horse flushed a desert hare (Lepus nigiricollis dayanus). Instead of fleeing, the hare stood its ground. Attributing the hares plucky behaviour to the quality of the soil and water of the place, Rajodharji built his capital there. Halvad remained the political capital of the Jhalas for three centuries and remains their spiritual capital till this day.

From Halvad two significant exoduses occurred, when the rightful heirs were denied the throne by palace coups. In the first instance, the ousted Ajoji, with his brother Sajoji, sought service with the Maharana of Mewar at Chittor, fought under his leadership against the Mughal emperor Babur at Khanwa, in 1527 CE, and when the redoubtable Maharana Sanga fell in battle, Ajoji led the Rajput confederacy till he himself was killed. Ajojis descendant, Jhala Rana Mansingh, saved the life of Maharana Pratap at the battle of Haldighati against Akbar.

The other instance of exile was that of the brothers Surtanji and Rajoji a century later. Surtanji founded the state of Wankaner, Rajoji that of Wadhwan, now Surendranagar.

C.E. Walker, the vice principal of St Stephens College, Delhi, once gave us a very sane piece of advice. One retires from one job or task to another, he said, but one retires from life only when one is dead or a dummy.

Many of my colleagues in the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) got busy writing their memoirs after retirement, and when I completed my service, well-wishers advised me to do the same. My father suggested that I write not just my life story, but about my times, of the transition of wildlife from princely and British India to the present, since he said, I had been a part of this change. However, I chose to continue with my interest in conservation and for viewing wildlife in as many parts of the world as possible. Recently, my daughters Meenal and Radhika and friends once again urged that I write, and after crossing the age of seventy-five, I realized that I do not have much time left. Hence, this text, before memory fades.

T he nine decades from 1857 to 1947 were, politically, the period of Pax Britannica and Indias growing aspirations to freedom. From the standpoint of natural history, it was the era of the breech-loading gun and the evolution of the hunting ethos; of Darwinism and the discovery of new species; and, finally, a nascent consciousness of the need to conserve nature, in India and the world over.

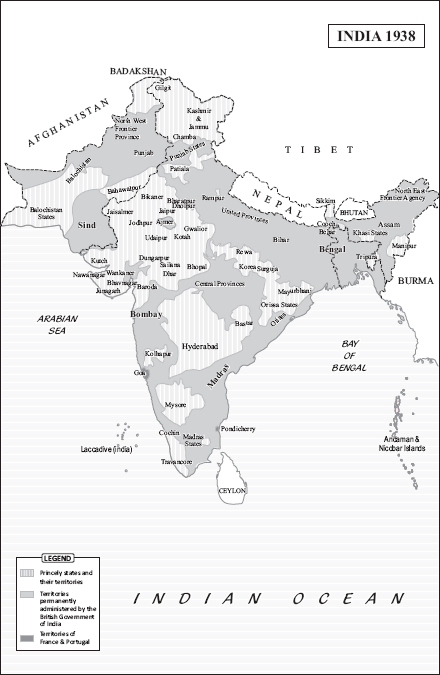

Some 60 km south of Halvad and 40 km north of the city of Rajkot, lies Wankaner, in the north-central part of the Saurashtra peninsula of Gujarat. Though recognized as a first-class princely state with a gun salute, Wankaner was small in comparison to the territories of other princely states. The premier states of Saurashtra (or Kathiawad as it was then called) were Junagadh, Jamnagar, Bhavnagar, Porbandar, Gondal and Dhrangadhra, in the last of which Halvad was situated.

In 1881, Banesinhji, the ruler of Wankaner, died and was succeeded by his two-year-old son Amarsinhji, my grandfather. Amarsinhji was the thirteenth descendant of Surtanji, the founder of Wankaner, and the forty-first after Harpaldev, the first Makwana-Jhala ruler. Banesinhji brought over from Porbandar state its deputy diwan, Karamchand Gandhi, and appointed him the diwan or prime minister of Wankaner. The child Mohandas, the future Mahatma, spent seven years in Wankaner before his father moved to Rajkot, where again he served as diwan.

In 1899, at the age of twenty, Amarsinhji was vested with full powers as the ruler of Wankaner. He inherited an almost empty treasury along with the worst famine in a century. Famine management, by way of irrigation tanks, was started with borrowed money and to supervise them he had to ride up to about 50 km a day, changing horses en route. In the next forty-nine years of his rule, Raj Amarsinhji left his mark on every square kilometre of Wankaner. He ruled personally, and not through a diwan.