Sarah A. Corbet ScD

S.M.Walters, ScD, VMH

Prof. Richard West, ScD, FRS, FGS

David Streeter, FIBiol

Derek A. Ratcliffe

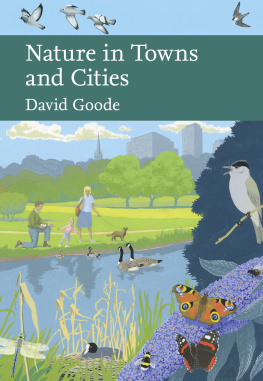

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists. The editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native flora and fauna, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research.

Dedicated to Derek Ratcliffe for reminding us that means should have ends, and that behind the posturing it is wildlife that matters

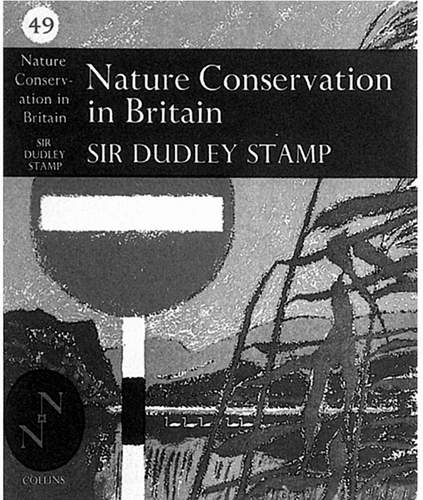

It is 32 years since Dudley Stamps New Naturalist on Nature Conservation in Britain appeared. Published posthumously, it summarised events and progress up to 1965, concentrating on the dominant role of the official Nature Conservancy. Since then, nature conservation has become much more fraught and politicised. It is in continual conflict with the forces of modern progress, in the increasing demands made on the natural environment by agriculture, forestry, mineral extraction, water use, energy supply, transport, urban development, recreation and defence. The voluntary bodies for nature conservation have also grown to rival the official side in importance. These massive shifts require a completely new book that takes over the story where Dudley Stamp left off.

Peter Marren is the acclaimed author of the 50th anniversary volume, The New Naturalists (1995), whose earlier career was in the Nature Conservancy Council. As a regional staff member in Scotland and later England, he saw things from the front line of nature conservation. His later role, in compiling its Annual Report, gave him an overview of the whole wide field of activities and issues in which the NCC became involved, and an insight into the frequently political nature of skirmishes with opposing vested interests. Then the NCC was devolved, and Peter found himself in English Nature, with a much reduced geographical remit and a new management-cum-public relations style. Unable to stand the combination of internal regimentation and external timidity, he resigned, to start a new career as a freelance writer on wildlife and its conservation. To this he brought a distinctive style, of fluent prose allied to sardonic wit, winning many fans who relish the appearance of his next work.

Peters perceptive eye has ranged over an astonishingly broad field in this new book, and he has told its complicated story with his usual flair. This is an honest appraisal of the net results of all the years of striving on behalf of wild nature in Britain an assessment of the balance between success and failure. He puts all aspects of the business under the microscope: the organisations concerned, the threats to nature, the measures for dealing with these, the politics involved, and the outcomes on the ground. The book is analytical as well as factual, but enlivened by its authors characteristic flashes of humour. This re-evaluation shows that, despite many successes in saving important wild places, plants and animals, losses have also continued on an unacceptable scale. Nature reserves do, at least, give us some tangible reward for all the effort, but the results from the persuasion approach are often more difficult to measure. In giving us this invaluable reference work, Peter Marren has also conveyed the richness and splendour of our national capital of wild nature, and its importance to our cultural heritage. Its defenders also have sombre lessons to learn from this synthesis if they are to improve their performance during this new millennium.

This is the first New Naturalist book on nature conservation since 1969. Its predecessor was written by Dudley Stamp, a geography professor and an influential voice in rural planning matters in the 1940s and 1950s. He was well qualified to report the early development of nature conservation in Britain, having been a long-time Board member of the Nature Conservancy, the original wildlife agency which he helped to set up in 1949. Stamp was also a well-practised writer of textbooks on geography and land use, and had contributed no fewer than four volumes to the New Naturalist library, including the outstandingly successful Britains Structure and Scenery. Nature Conservation in Britain was his last book, published after Stamps untimely death in 1966. It was a mellow look back at the past, broadly successful, quarter-century, in which conservation had developed from the hopes of a few naturalists to a broad-based going concern with its own mini-department in government. It was a relatively short book, concentrating on the work of the Nature Conservancy and the county wildlife trusts, and listing nearly all the nature reserves existing at that time.

Thirty years on, that world has changed utterly. Conservation has become a much more pluralist activity involving many sectors of society, both official and voluntary. It has broadened out from its original base in natural history to address fundamental issues like the future of the countryside and the claims of the urban majority on how land is used, and whether we should be allowed open access to it. It has become ever more difficult to say where nature conservation ends and concern about our own futures begins. Indeed, the very phrase nature conservation means something different today. It is now shot through with fashionable concerns like sustainability, animal rights and habitat creation, some of which might have baffled the conservationists of the 1960s, whose perceptions were rooted more in natural sciences and the development of institutions.

Nature Conservation in Britain (1969). The dust jacket designed by Clifford and Rosemary Ellis was inspired by the Abbotsbury swannery in Dorset, Britains oldest bird sanctuary.

Even so, many of the things Dudley Stamp was writing about are still with us. We still conserve wildlife by setting up nature reserves, or designating private land as Sites of Special Scientific Interest. What has changed more is the scale of the resources brought to bear on protecting nature. Bodies like the RSPB and National Trust have more members than any of the political parties or trades unions. Money has flowed into the business (as it has become) from the Heritage Lottery Fund, tax credits and the EU LIFE fund. We stand on the verge of a major shift of agricultural subsidies from food production to sustainable land use. If I was writing this book from the perspective of conservation bodies, that is, in terms of wealth and influence, it would be a story of unalloyed success. Instead, I have chosen to write it, as far as possible, from the more awkward perspective of wildlife. I try to assess to what extent all this power and money has benefited British wildlife, and how far the undoubtedly frenetic activity of the recent past has translated into policies that improve the lot of rare and declining species and wild places. Is the countryside in better shape today than in 1969? Do we have more wildlife now than we had then? Perhaps we should have. The population has hardly grown in that time, and the polluting industries of the 1960s have either cleaned up their acts or disappeared. Persistent pesticides are no longer widely used. And yet the statistics show a steady loss of habitats and species. Although in some ways land use has become more environment-friendly, a short walk with open eyes almost anywhere in Britain is a good antidote to the wilder claims of the prophets of the Things are Much Better Now school.