All rights reserved.

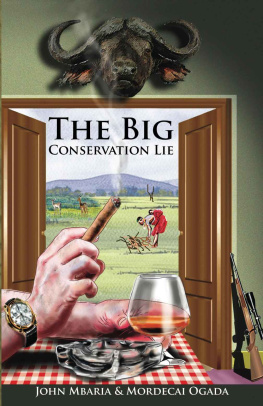

To our Ancestors, who lived with, used, and conserved our biodiversity without being paid crumbs to do so.

To those of us who struggle today to wrest this most precious resource from the grip of an avaricious elite.

And to our children and the unborn who, we hope, will appreciate this bounty and never forget that it is their birthright.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book has been a very long time in the making, not because of the time taken to write it, but the combined years of experience in different fields that yielded this collection of thoughts. We would like to sincerely thank all those who crossed our paths and nourished us intellectually. We would like to mention the following, Dorothy Wanja Nyingi, Joyce Nyairo, Michela Wrong, Wanjiku Kiambo, Andy Hill, Laurence Frank, the late Anthony King, and William Pike.

There are others who took us through lifes lessons, whipped us into line, and enabled us to eventually realize this and other dreams. With fond memories, we mention Francis Mbaria, Mary Waithera, the late Evans Kamau (a former English teacher of Kibubuti Primary School), Mwalimu Bulderick Ogange, Purity Kendi, and Ali Nadim Zaidi. We specially thank Ambassador Nehamiah Rotich for ably demonstrating that local talent and professionalism is what is needed to effectively manage the Kenya Wildlife Service.

This book has been a journey in discovery of our country, our society, our traditions, our weaknesses, and our strengths. In the discussions we had on social media, there were so many friends who shared insights, thoughts, and encouragement that made us see the value of this work, long before it was complete. David T. Mbogori, Loiuza Kabiru, Said Wabera, Koikai Oliotiptip, Mali Ole Kaunga, Dennis Morton, Kiama Kaara, Alexia Trombas, Franky Kago, Noni Mbatia, Gichena Chacha, Salisha Chandra, Kipruto Kertiony, Kariuki Kiragu, Pieter Kat, Hawi Odingo, Mutemi wa Kiama, Njenga Kahiro, Elizabeth Wamba, Mike Mills, Nelson ole Reiyia, Leonard Lenina Mpoke, Leonard Omullo, Munene Kilongi, and Geoffrey Kamadi

Last but not least, Skeeter Wilson, for believing in our work, and Trevor O'Hara, John Nyagah, and Eddie Obinju for your respective roles in making this a reality.

Our sincere gratitude to you all.

The Epiphany

John Mbarias Encounter With Unseen Injustice

S he was an unmistakable image of deprivation. The emaciated Samburu woman had thrown across her left shoulder a torn shuka , which left parts of her body exposed. She had braved the sweltering Samburu sun that baked the entire place bringing into being mirages of promise that failed to deliver more than that. As she advanced to the river, the woman attempted an upright position. But her stooped frame refused to yield. Nevertheless, this enabled me to peer into her cracked, multilined face. Her look was distant. Her thin hands held onto a cord with which she had strapped the empty twenty-litre water jerrican. Her entire frame talked of many struggles and probably as many defeats. The woman had emerged from a thick bush across the river, itself part of a natural spread dotted here and there by short, sturdy trees and broken, now and then, by awkward-looking hills. Some of the outcrops had been whitened by excrement from birds of prey. The vast, monotonous terrain extended into the distant horizon, giving packs, herds and flocks, and other residents a veritable abode. Some did not just live and let live; they visited local peoples homesteads with danger and intent. Across the river was a scene removed from the reality of this unforgiving landscape. Under the watchful eyes of armed rangers, a group of us were happily and noisily climbing a rocky landform that formed part of the rivers embankment.

This was in 2001, and most of us were young, joyful journalists. We had been sponsored to the Shaba Game Reserve, 314 kilometres northeast of Nairobi, by the Sarova Group of Hotels, one of Kenyas most prominent hotel chains with eight hotelsmany of which are carefully stashed in some of Kenyas most spectacular, most pristine pieces of wilderness. Located in Eastern Kenya, Shaba is where the popular reality TV adventure series Survivor III was shot in August 2001. Before that, the game reserve hosted Joy and George Adamson, the romantic conservationists who gave the world a reality show of life in the bush before they were tragically murdered. Together with its sister reserve, Buffalo Springs, Shaba boasts of seventeen springs that sojourn along subterranean courses from Mount Kenyaone hundred or so kilometres awayand which gush out there to convert part of this dry wasteland into a veritable oasis. Along its northern boundary flows the Ewaso Nyiro River that, together with the springs, has made the entire place a magnet for gerenuks, Grevys zebras, reticulated giraffes, lions, leopards, and hundreds of bird species that live side by side with the Samburu people. We were taken there to savour the unmitigated joy of spending time in a purely wild area. We were expected to reciprocate by meeting our briefflowery feature stories embellished into captivating narratives that could attract and keep guests visiting the hotel and the reserve. Many of us were poorly paid cub reporters who could hardly afford the European cuisine on offer or the joys of partaking of a game drive atop four-wheel-drive fuel guzzlers. With a monthly pay that either equaled or was slightly more than the cost of spending a night in the extremely comfortable and luxurious hotel, we could not but agree to be spoiled for three days and be blinded by freebies. We roamed the area in vans packed with bites, booze, and soda. For lunch and dinner, three-course meals of continental dishes awaiteda veritable feeding frenzy ensued.

While on game drives, we hoped to spot elephants, dung beetles, and everything in between. Part of our exclusive experience included climbing a rocky landform close to the crocodile-infested Ewaso Nyiro River. It was while doing so that I spotted the elderly Samburu woman. Silentlyalmost in mimeand removed from my world, she was to take me through a host of lessons that dramatically altered my entire outlook on the grand wildlife conservation program Kenya and other countries in Africa have adopted since the dawn of colonialism.