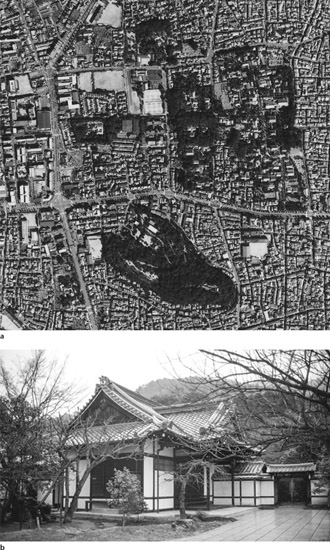

Figure 1.1a, b and c Aerial view of the Mt. Funaoka Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto (a), Japans capital from 794 ce until 1868. Wooded areas in the image generally mark the locations of Kyotos 198 noted historic buildings and gardens, thirty-eight of which are designated National Treasures and 160 are Important Cultural Properties. The seventeenth century imperial convent of Reikanji (b) represents one of Kyotos several Buddhist monastic structures and the Kinkakuji (Temple of the Golden Pavilion) (c) represents a secular structure. Clad in gold leaf, the Kinkakuji originally dating from the 1390s as a retirement villa for Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu. Destroyed by fire in 1950 and it was faithfully reconstructed in 1955. Its gold leaf exterior finishes were restored in 1987.

Architecture on a monumental scale first appeared in Japan with the construction of earthworks and religious buildings, during the early first millennium CE . The Kofun period (250 to 538 CE ) and the Asuka period (592 to 710 CE ) witnessed the construction of hundreds of large earthworks. The key-shaped burial mounds ( kofun ) can be found almost everywhere in Japan, especially on its western coast, and are famous particularly in the Osaka and Nara areas, where they symbolize the Yamato court. This tradition disappeared with the arrival of Buddhism and the reorganization of the Yamato court in Nara in the mid-seventh century CE . This period saw greater contact with China and incorporation into Japanese building styles of the architectural vocabulary of stupas and temples.

The early imperial court in Japan relocated after the death of each successive emperor, meaning that there was not one permanent site on which a multi-generational capital could be constructed. However in 710 ce, influenced by contact with the Chinese court in Changan, the imperial court began constructing a palace complex in what is now Nara. Nara contains a number of buildings that have survived from this time, the Asuka period, including the Hry-ji temple complex that houses possibly the worlds oldest surviving wooden structures likely dating from 670 CE .

After a brief stop in Nagaoka-ky, the imperial court moved to Heian-ky (present day Kyoto) in 794 CE . Kyoto would be the seat of imperial power for over 1,000 years, until 1869. and the extraordinary Ninomaru Palace in Kyotos Nij Castle.

A long tradition of moving buildings exists in Japan, as can be seen in the practice of an emperor or member of his family donating parts of their palace for integration into a monastery or convent. The inherent capacity of wooden architecture to be easily dismantled and rebuilt made moving and rebuilding structures commonplace. and the specific requirements of maintenance through repair and rebuilding of wooden artifacts have heavily informed the specialized heritage conservation ethos in Japan.

To some extent, the prevailing conservation attitudes in Japan have set it apart from the larger global architectural conservation community. For instance, Japan did not adopt the ICOMOS Venice Charter in 1964 for several reasons. While the charter was recognized and most of its tenets have been respected, it was perceived by Japan and some other non-European countries from the onset that the monuments-centric assumptions of the Venice Charter could not readily be applied to building typologies such as wooden religious buildings and the countrys less durable wooden vernacular buildings. Such buildings require more frequent maintenance and repair, including occasional replacement of whole parts, a type of conservation intervention that counters notions of conserving material authenticity. This practical reality plus the fact that Japan has maintained a continuity of traditional building skills and methods has helped distinguish Japanese architectural conservation as being in a category of its own. Of importance as well is the other practical reality that the Venice Charter was not an international convention that could be adopted at the intergovernmental level. Thus it could never have been more than only acknowledged, respected and complied with as much as possible. Preserving the historic building fabric comprising many of Japans monumental structures in honor of its age, patina and authenticity is practiced, in spite of the relative impermanence of traditional Japanese building materials. This is especially true of elaborate wood joinery, fine temple fittings, furnishings and statuary, as seen in some of Japans earliest temples, shrines and museum collections at heritage sites in Kyoto, Nara and elsewhere. Thus, generalizations about Japanese architectural restorers and preservationists never caring about preserving authenticity are not well founded.