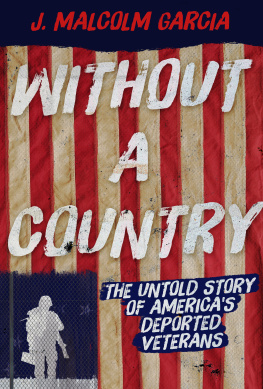

Copyright 2014 by J. Malcolm Garcia

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved

5 4 3 2 1 18 17 16 15 14

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8262-2021-9

ISBN 978-0-8262-7326-0 (ebook)

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

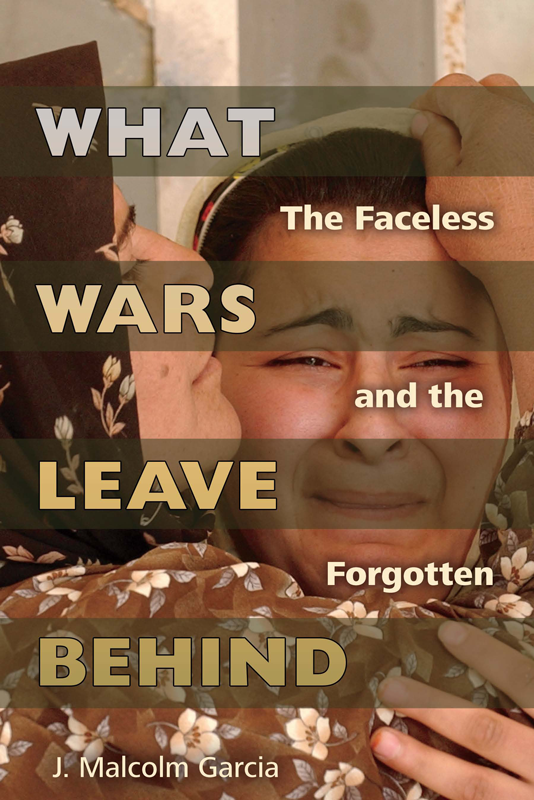

Jacket design: Kristie Lee

Interior design and composition: Bruce Leckie

Typefaces: Alia JY, Myriad Pro

Acknowledgments

My deepest thanks to the editors of Ascent Magazine, Guernica: A Magazine of Art & Politics, McSweeneys, New Letters, Southampton Review, Superstition Review, Vice Magazine, and Virginia Quarterly Review for first publishing these stories.

Jesse Barker, Scott Canon, Heather World, Doug Worgul, Chuck Murphy, Leonore Dvorkin, and Lucian Truscott IV all read early drafts of these stories and often read them more times than any one person should. I cannot thank all of you enough for your critiques. And no, Im sorry to say, my spelling and punctuation has not improved despite your best efforts.

Everyone at University of Missouri Press has made this a wonderful writing experience, especially Clair Willcox, Sara Davis, Kristi Henson, and others whose names I do not know but who also put their time into the making of this book.

I especially want to thank Polly Kummel for her insightful copy edits line by line, paragraph by paragraph, page by page. I learned from you and am a better writer for it.

As always, thanks to Stella Ferrer, David Littlejohn, Dale Maharidge, and Scott Olsen for their encouragement and Molly Giles for her patience with my first strained efforts at storytelling.

Finally, I want to thank my former colleagues at the Ozanam Center and Hospitality House in San Francisco and the homeless men and women I once worked with there. All of you supported my first hesitant steps toward journalism. I wont forget you.

Introduction

I slipped, fell, and started sliding off the rock ledge. I reached for a sapling, roots, anything, waving my arms until finally I seized the prosthetic leg of the man behind me as I passed him. He clung to the arm of a man ahead of him, and together they pulled me up. Shaken, I sat beside him on the ledge fronting the entrance to his cave.

You dont look too good, but your leg is strong, an old man said to the man who helped me.

The three of us laughed. The year was 2002. July. I was filing a story from the Afghan city of Bamiyan, about a ten-hour drive north of Kabul and known best for the Buddha statues that had been carved into the cliffs in the sixth century. They were destroyed in March 2001 after the Taliban government declared they were idols and therefore sacrilegious.

Those cliffs then housed about 200 mostly ethnic Hazara families. Desperation drove them there. It was windy. It was boiling hot in the summer, frigid in the winter. It was hard to reach. It was easy to slip on the loose gravel and narrow footpaths. A mans prosthetic leg had just saved me from tumbling down a mountain. I was alive, sitting outside a remote cave with destitute war survivors and dying for an ice-cold glass of water. Instead I got what I came for: a story.

The man with the prosthetic leg told me that in 1994 he had stood here and watched the Taliban battle their way into Bamiyan. He saw men and women killed by machine guns and mortar fire. He left and walked to Kabul. He stepped on a mine and lost his leg. He had only recently returned. Before, he said, he had a home. Now he had a cave.

The Hazara are the dominant ethnic group in Bamiyan and date to Genghis Khans warriors. In the late 1990s reports of Taliban fighters massacring Hazara men, women, and children in northern and central Afghanistan were common. The Taliban ransacked and destroyed homes.

After the Taliban were routed by the American-led international military coalition that invaded Afghanistan a little more than a month after the World Trade Center fell, Hazara families returned to villages that had been reduced to rubble. So they resorted to the caves, an uneven patchwork of openings across wind-chiseled rock. The caves interconnect like a beehive above the ruined city.

When I arrived in Kabul in November 2001 on my first overseas assignment, I knew little about Bamiyan and the slaughter of the Hazara and even less about Afghanistan. I knew social work because thats what I did until I was forty, when I decided to break into journalism. At the time, 1997, I was more than a little worried that, to follow a new calling, that of the wandering scribe, I had just thrown away a successful fourteen-year career helping homeless people.

Four years later I got my first glimpse of the consequences of war. Kabuls downtown was a giant rock pile of bomb-blasted buildings destroyed during decades of wars. Men with turbans and thick beards wandered the streets in frayed sandals. Donkeys pulled carts. Women drifted by in billowing body-length veils. Boys pushed wheelbarrows filled with grinning goat heads. Older boys shouldered Kalashnikovs. The broken streets teemed with commotion and dust and the shouts of vendors and the supplications of beggars. Makeshift camps without water or plumbing overflowed with refugees.

I returned to the States three months later and felt lost. I couldnt stop thinking about Afghanistan and the vacant stares I had absorbed from people who had lost everything. So I put them out of my mind by returning to Kabul again and again to be among them. No longer were they memories trapped inside my head but real people I lived with and who told me their stories. I also became acquainted with photographers from Europe, Asia, and South America. They pitched editors story ideas they had for Pakistan, the Middle East, and Africa. We hooked up, and I began writing about the poor and forgotten families I encountered along the way.

The people I have met and continue to meet in my travels across the globe move me, and I am angry that their suffering so easily falls beneath the radar of news coverage. I write about them because their anguish is what wars leave behind, what corruption and ineptitude and sheer meanness leave behind. I am drawn by the detritus of human upheavalthe prosthetic leg that may have saved my lifenot the thrill of the kill.

I wrote the stories in this collection between 2004 and 2013. They take place in Kosovo, Chad, Egypt, Syria, and Afghanistan and Pakistan; the last two countries are where I have spent most of my time overseas and where American policy has played a large role. The stories reflect my interest in people who face problems I find hard to imagine: a mother seeking the release of her imprisoned son in Cairo, American soldiers on patrol in Kabul, Syrian children surviving as refugees. These people and others live in a universe parallel to the one the rest of us take for granted, with a roof over our heads, meals on our tables, the noise of children playing, the humdrum security of our lives. Yet we are not that far removed from the forgotten and overlooked. An unanticipated event such as the recent recession can devastate our lives in a flash and turn a comfortable dinner at home into a trip to the soup kitchen and a soiled mat on a gymnasium floor.

Reporting helps keep the world real for me, making it a tangible place where people live, breathe, survive, and occasionally triumph in ways that may seem dwarfed by their circumstances. I thrive by going to places Ive never been and relying on instinct to ferret out the people stories lurking below the surface of the news.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.