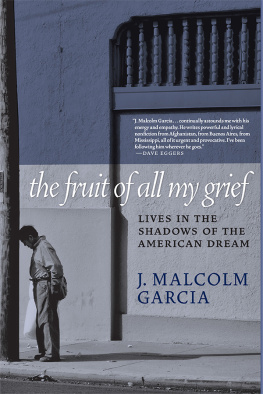

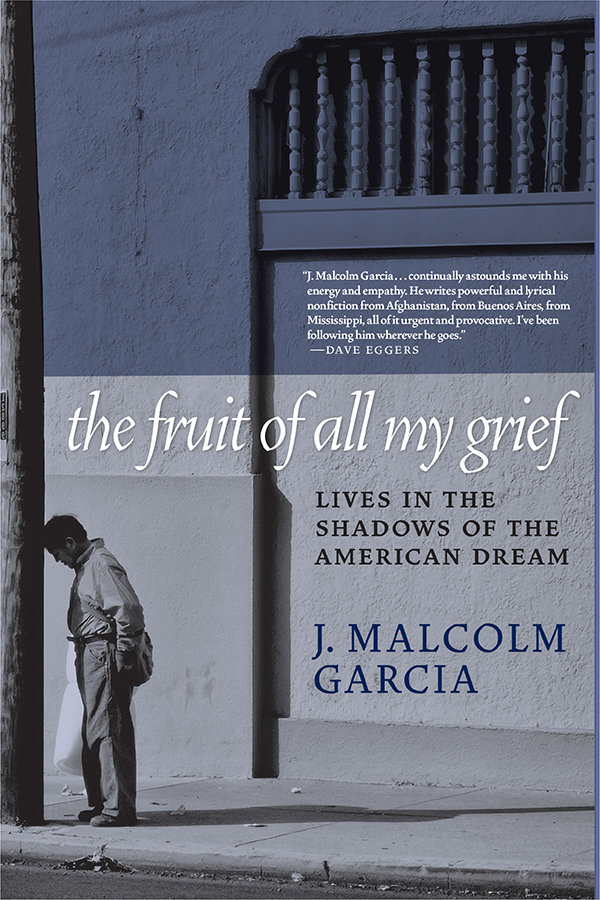

the fruit of all my grief

Lives in the Shadows of the American Dream

J. MALCOLM GARCIA

Seven Stories Press

New York Oakland London

Copyright 2019 by J. Malcolm Garcia

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

www.sevenstories.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Garcia, J. Malcolm, 1957- author.

Title: The fruit of all my grief : lives in the shadows of the American dream / J. Malcolm Garcia.

Description: New York : Seven Stories Press, [2019]

Identifiers: LCCN 2019017120 | ISBN 9781609809539 (paperback) | ISBN 9781609809546 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Social problems--United States. | Marginality, Social--United States. | American Dream. | United States--Social conditions--21st century.

Classification: LCC HN59.2 .G35 2019 | DDC 306.0973--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019017120

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

College professors and high school and middle school teachers may order free examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles. To order, visit www.sevenstories.com, or fax on school letterhead to (212) 226-1411.

These stories appeared, some in different versions, in Guernica: A Magazine of Arts& Politics (Fishing with the King, November 2010; The Life Sentence of Dicky Joe Jackson and His Family, April 2014; Sanctuary, March 2017); The Massachusetts Review (Nothing Went to Waste: Considering the Life of Ben Kennedy, Summer 2012); McSweeneys (What Happens After Sixteen Years in Prison?, January 2013); Oxford American (Smoke Signals, Summer 2011; New Missions, Spring 2012; and Backyard Battlefields, Summer 2012); River Teeth (And the Walls Came Tumbling Down, Fall 2012); Virginia Quarterly Review (A Product of This Town, January 2008); and The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2009 (We Are Not Just Refugees, Summer 2009).

Take from my hand

Put in your hands

The fruit of all my grief

Alabama Shakes

My eyes often open when I see a limping person going down the street.

That persons wrestled with God, I think.

William Goyen

Contents

Preface

The first story in this collection, Sanctuary, came about as I followed news accounts of President Trumps initial crackdown on undocumented people in 2017. I contacted organizations that worked with immigrants and learned about a Mexican man, Sixto Paz, who had taken refuge in a Phoenix, Arizona, church for almost a year. I wondered, Who is this guy and others like him? Beyond the one or two quotes attributed to them in news stories, who are they, really? What are their dreams, ambitions, their disappointments? They are statistics. What else are they? What is our breathless, twenty-four-hour news cycle missing about them? I had to find out. I contacted the church and arranged to meet Sixto.

I often find my stories through the news and in chance encounters. In 2005, I was reporting from Port-au-Prince, Haiti, when I met a man by the name of Michael from Texas who housed homeless teenage boys. We spent no more than an hour together, if that. Five years later, after a catastrophic earthquake struck Haiti and killed thousands of people, I thought of Michael and wondered if he and the boys he sheltered survived. I tracked Michael down and then flew to Port-au-Prince and spent ten days with him as he tried to rebuild his shelter, his life, and the lives of the children he cared for.

Sixto, Michael, and the others profiled in this collection survived their ordeals. Their struggles changed and defined them, as do our own. They give meaning to our lives. They are our history and often reflect the times in which we live. They are worth telling and retelling and remembering.

The lives lurking beneath the surface of the everyday continue to intrigue me. My initial judgment of someone I dont know, based on the slimmest of informationtheir appearance, the sound of their voice, their expressionsdoes not satisfy.

We will continue to make assumptions about strangers through the impressions made by the briefest of encounters. No matter how flawed those conclusions, no matter how different we may think we are from them, most of us share a common routine. We get up each morning. We make it through each day. We sleep at night and ready ourselves for the next day without knowing what it may hold, what challenges well have to surmount, and how others will judge us.

We persevere.

J. Malcolm Garcia

San Diego, February 2019

Sanctuary

Sixto Paz opens a door and shows me the music room. He sleeps on a bed across from a piano, sheets neatly tucked, a rack of clothes on hangers beside it. Shelves of books. A whiteboard. A table, some chairs, and a well-thumbed Bible open to the Book of Genesis. Sixto crashes out at about midnight and wakes up at four. He has trouble sleeping.

His last night in his Lexington Avenue place. Well... he hadnt known it was his last night at home in Phoenix. He knew he might have to leave, adapt to something not his home, to this church, but when? He had tried not to think about it. Leave family, leave work, leave his life, and come here and do nothing but wait for people he did not know to decide his fate. No, he would put that thought off as long as he could.

Sixto is forty-eight. He moved to the States from Mexico at the same time the Reagan administrations 1986 immigration law passed Congress. Among other things, the law admitted undocumented laborers for temporary and in some cases permanent residence. Sixto worked and traveled freely and legally in and out of the country. For more than twenty-five years, he built a life in Phoenix. He fathered a family, two daughters and a son, all U.S. citizens. He has no criminal record. But in2002 the Department of Homeland Security refused to renew his work permit, which had given him authorization to work as a nonimmigrant. Sixto blames the decision on changing immigration laws fueled by a populist backlash that accused immigrants of taking jobs from American citizens.

Seven years later, in 2009, he was stopped at a checkpoint near Yuma, Arizona. He was charged with remaining in the United States longer than his work permit allowed and held at a service processing center near Phoenix. He spent the next seven years fighting deportation in court. His attorney, Jose Pealosa, told me that he always knew the court might rule against Sixto. He had heard that Shadow Rock United Church of Christ in North Phoenix offered sanctuary to undocumented migrants. Federal immigration and border authorities in most cases avoid detaining people who are staying in churches, schools, and hospitalssensitive locations, according to a 2011 Immigration and Customs Enforcement memo.

Pealosa presented Sixtos situation to the church board in April 2016, and the board agreed to offer sanctuary. Then, in May, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals lifted a stay of removal, paving the way for Sixtos deportation.

Pealosa called Sixto. Its time to go into sanctuary, Sixto recalls him saying.

Sixto was installing a roof. He didnt know anything about roofing when he started in the early 1990s. Now he does. He can shape any piece of metal, any kind of material. Just ask him and hell do it. Hes worked with Mexican tile, Eagle tile, clay tile. He has done roofs on army bases and schools and in residential neighborhoods. Hell build you a roof from scratch, if you want.