Contents

Guide

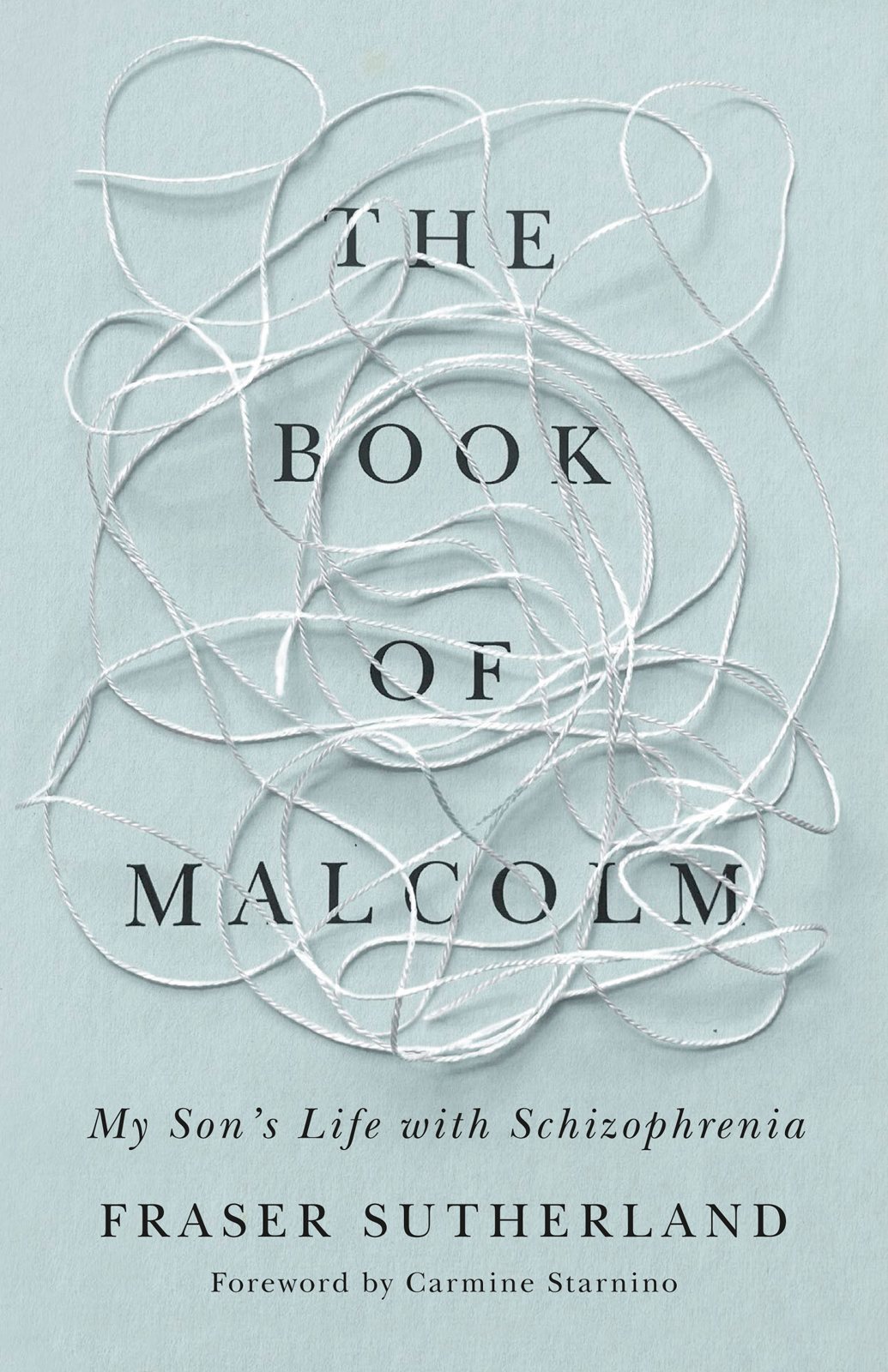

THE BOOK OF MALCOLM

THE BOOK OF MALCOLM

My Sons Life with Schizophrenia

FRASER SUTHERLAND

Foreword by Carmine Starnino

Copyright Fraser Sutherland, 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purpose of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Publisher: Scott Fraser | Acquiring editor: Russell Smith

Cover designer: David Drummond

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: The book of Malcolm : my sons life with schizophrenia / Fraser Sutherland ; foreword by Carmine Starnino.

Names: Sutherland, Fraser, author. | Starnino, Carmine, writer of foreword. Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20210297557 | Canadiana (ebook) 20210297913 |

ISBN 9781459749566 (softcover) | ISBN 9781459749573 (PDF) | ISBN 9781459749580 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Sutherland, Malcolm, -2009. | LCSH: Sutherland, Malcolm, -2009Mental health. | LCSH: SchizophrenicsCanadaBiography. | LCSH: Schizophrenics Family relationshipsCanadaBiography. | LCSH: Sutherland, FraserFamily. | LCSH: Parent and adult childCanada. | CSH: Authors, Canadian (English)Biography. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC RC514 .S88 2022 | DDC 616.89/80092dc23

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Ontario, through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and Ontario Creates, and the Government of Canada.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

The publisher is not responsible for websites or their content unless they are owned by the publisher.

Rare Machines, an imprint of Dundurn Press

1382 Queen Street East

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4L 1C9

dundurn.com, @dundurnpress

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Carmine Starnino

A S A WOLFISH young critic, hungry to offend, I loved Fraser Sutherlands thought crimes. Margaret Atwoods famous critical study Survival was the most misleading thematic summary ever perpetrated against a gullible public. Anne Carson, for all her international laurels, was a poet of distracting academic archness and clutter. Jack Hodginss celebrated fiction was tiresomely ramified melodrama. Sheila Watsons classic novel Double Hook surely rivals Leonard Cohens Beautiful Losers for unreadability (a lovely, and rare, trick of the double takedown).

Fraser was, no denying it, a tough customer. He reviewed books mostly for the Globe and Mail, and in interviews he seemed toughest on colleagues willing to give everything a free pass a club I was determined not to join. (Im dismayed, he once said, at how little independence and real dissent gets expressed.) But what also caught my eye when reading him were the parts of his writing that caught my ear. The man could turn a phrase. What went into that phrase-turning was a lifetime revelling in language. Fraser earned his living as a freelancer, where fluency is currency. Starting out as a reporter and staff writer in 1970s, he transformed himself into a formidable literary journalist. A self-taught lexicographer, he edited and wrote definitions for dictionaries. Sometime in the 2000s, he set up a side hustle as a brand-name consultant, coining names for companies and products. Frasers appreciation of words as physical items with weight and volume, drag and propulsion led to a style that joined precision and plain sense a style that, as I learned when we became friends, extended to his personality.

Fraser was rarely over-awed; rather, he was tetchy. He was also funny in a way that wasnt always funny, but wary. He had a wit that kept everything down to earth. He was a useful corrective, always subtly right-sizing the few enthusiasms I allowed myself. You are especially generous to the young and starting-out, he warned me in an email, who of course should be discouraged as much as possible. He had lived all over the country Halifax, Ottawa, Montreal, and Nelson, B.C., before settling in Toronto with his wife and son and picked up an alarming store of literary gossip, the most damning from the late 1960s and 70s. Watching him, over a pint, drop a tell-all anecdote about a Famous Canadian Writer wasnt just entertaining: it helped strip away any illusion about reputations. Its hard to believe in the showbiz version of CanLit when you know a bit about the quasi-incestuous pile-on of its early days.

There was something wonderfully ad hoc and unsystematic about Frasers mind. He once described himself as a displaced, unreconstructed Nova Scotian farm boy, and the breadth of subjects he followed (and reviewed, with authority) showed that he put no restraints on his enthusiasms. Sutherland was also obsessive. A natural researcher, the fear of excluding a detail often overtook him. His book-length poem, Jonestown, took fifteen years to complete; his biography of poet Edward Lacey, twelve.

Frasers insights felt hard-won. They also, I wager, came at a cost. There was a sadness to him the sadness of a man who tried hard to tell the truth; the kind of truth that was always unfashionable. Fraser often seemed alone, even among friends (and sometimes especially). That sadness got into his poems, which explored ideas of exile and self-isolation, and which seemed written (at least to me) in his darker hours. Connecting with the other, he once said, is a way of connecting with the otherness within myself. Frasers activities as a literary arbiter and self-declared counterpuncher so coloured his career that it could be surprising to see what his poems were up to. The close-at-hand observations (I awoke this morning to a solitary chainsaw / cracking and ripping the country air), the head-clearing insights (These are days when I would want to begin again / in some stranger-city), the raw moments remembered and reflected on (First I was lonely / Then I was depressed.) While he sometimes tried out more bardic tones, his voice had little of the ego-posturing he loathed in contemporary poetry. In fact, the curmudgeon could be downright disarming:

When we talk, youll notice

I do not look directly

at you but downward or ahead, my good ear

inclined toward your words, now

and then glancing briefly at you to affirm

I am still listening, still there.

Those lines, which open Looking Away, show no trace of the self-important demands of a busy career as an editor and critic. They are not the lines of someone who wants to win over juries or who is fighting to stay in the swim of a literary scene (If the trappings of public success, however welcome, began to descend on me, he said in an interview, Id start to suspect myself). They belong to a man who wants to say a few meaningful words about being in the world. The best of Frasers poems are quiet dramas of distress. You wouldnt call them candid; they are vulnerable, unsentimental, confiding as if unwittingly / hes strayed into a life. They take on modest, uninflated forms, finding the truth a foot in front of me.