L. C. catalog card number: 559290

Sigurd F. Olson, 1956

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

Copyright 1945, 1948, 1951, 1955, 1956 by Sigurd F. Olson. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Manufactured in the United States of America and distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Published April 16, 1956

Reprinted Seventeen Times

eISBN: 978-0-307-81990-1

v3.1

To

those who know and love that rugged wilderness

of rivers and lakes and forests

known as the Quetico-Superior Country

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I AM DEEPLY GRATEFUL FOR the help and encouragement of members of my family, especially that of Elizabeth and Vonnie; for the advice and understanding of friends who have read many of the chapters. I also wish to express my appreciation to Francis Lee Jaques for his superb portrayal of the North Country.

Certain of the chapters in this book previously appeared in magazines, occasionally under different titles. My thanks for permission to reprint them here are due to: North Country, The Living Wilderness, Sports Illustrated, Gentry, National Parks Magazine, Sports Afield, and The Gopher Historian.

Contents

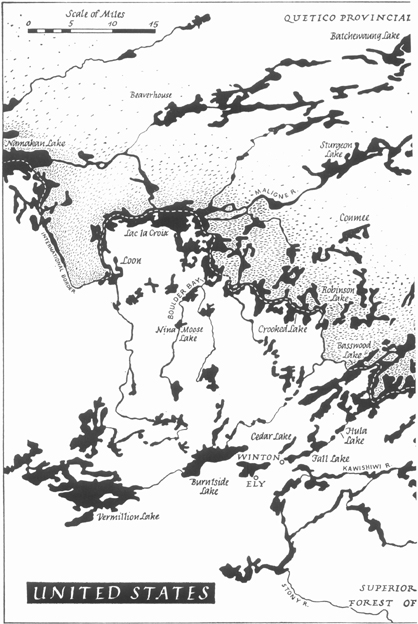

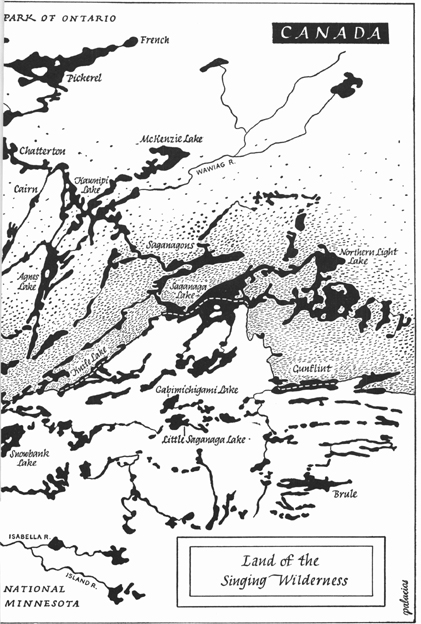

THE SINGING WILDERNESS

THE SINGING WILDERNESST HE singing wilderness has to do with the calling of the loons, northern lights, and the great silences of a land lying northwest of Lake Superior. It is concerned with the simple joys, the timelessness and perspective found in a way of life that is close to the past. I have heard the singing in many places, but I seem to hear it best in the wilderness lake country of the Quetico-Superior, where travel is still by pack and canoe over the ancient trails of the Indians and voyageurs.

I have heard it on misty migration nights when the dark has been alive with the high calling of birds, and in rapids when the air has been full of their rushing thunder. I have caught it at dawn when the mists were moving out of the bays, and on cold winter nights when the stars seemed close enough to touch. But the music can even be heard in the soft guttering of an open fire or in the beat of rain on a tent, and sometimes not until long afterward when, like an echo out of the past, you know it was there in some quiet place or when you were doing some simple thing in the out-of-doors.

I have discovered that I am not alone in my listening; that almost everyone is listening for something, that the search for places where the singing may be heard goes on everywhere. It seems to be part of the hunger that all of us have for a time when we were closer to lakes and rivers, to mountains and meadows and forests, than we are today. Because of our almost forgotten past there is a restlessness within us, an impatience with things as they are, which modern life with its comforts and distractions does not seem to satisfy. We sense intuitively that there must be something more, search for panaceas we hope will give us a sense of reality, fill our days and nights with such activity and our minds with such busyness that there is little time to think. When the pace stops we are often lost, and we plunge once more into the maelstrom hoping that if we move fast enough, somehow we may fill the void within us. We may not know exactly what it is we are listening for, but we hunt as instinctively for opportunities and places to listen as sick animals look for healing herbs.

Even the search is rewarding, for somehow in the process we tap the deep wells of racial experience that gives us a feeling of being part of an existence where life was simple and satisfactions were real. Uncounted centuries of the primitive have left their mark upon us, and civilization has not changed emotional needs that were ours before the dawn of history. That is the reason for the hunger, the listening, and the constant search. Should we actually glimpse the ancient glory or hear the singing wilderness, cities and their confusion become places of quiet, speed and turmoil are slowed to the pace of the seasons, and tensions are replaced with calm.

I remember vividly the first time I heard the music. It was near the tip of a bold peninsula that reached far out into Lake Michigan, and though I was only seven at the time and knew nothing of the need of solitude, or the hunger I have known since, the response was there. The moan of foghorns and the deep-throated whistles of lake boats were part of my childhood dreams. We lived inland, and I used to lie awake at night and listen to them far out in the dark and wonder at the mystery of the night that engulfed them.

The time came when I felt I must go to the lake through the forest that lay between, see for myself the open reaches of water, the ships whose voices I had heard, the waves and cliffs of the coast. One day, all alone, I started out through woods I had never traversed. At that time there were lynx and wildcats there and I had heard gruesome stories of how they lay in wait to pounce on wanderers passing through. I ran most of the long, winding trail, and when I burst at last out of the gloom I was frightened and breathless. Before me were space and a sparkling blue horizon, with no land as far as I could see. An abandoned pier reached out from the shore and I picked my way over the huge blocks of stone to its very end. There I found a deep well of clear water down between them.

A school of perch darted in and out of the rocks. They were green and gold and black, and I was fascinated by their beauty. Seagulls wheeled and cried above me. Waves crashed against the pier. I was alone in a wild and lovely place, part at last of the wind and the water, part of the dark forest through which I had come, and of all the wild sounds and colors and feelings of the place I had found. That day I entered into a life of indescribable beauty and delight. There I believe I heard the singing wilderness for the first time.

I kept the pier a secret and stole away there as often as I could. It was the answer to all of my childish desires, a place of magic and wonder which belonged to me alone. My perceptions were uncluttered, my impressions were pure and uninfluenced, my feelings of closeness to nature and of sympathy with creatures of the wild were true feelings. In them, I know now, was that ancient realization of oneness so hard to know or recognize as life becomes more involved. John Masefield, in speaking of his own first contact with what he called the greater life, said: I believe that life to be the source of all that is of glory and goodness in this world and modern man not knowing that life is dwelling in death.