Want more from The Economist?

Get sneak peeks, book recommendations, and news about your favorite authors.

Tap here to find your new favorite book.

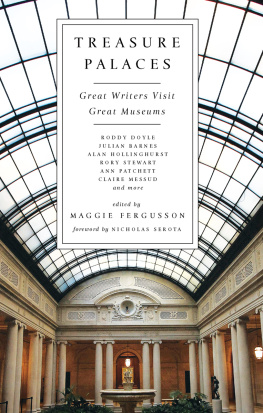

TREASURE PALACES

MAGGIE FERGUSSON was for many years the literary editor of The Economists lifestyle magazine, Intelligent Life, and is author of two biographies, George Mackay Brown: The Life and Michael Morpurgo: War Child to War Horse.

The Economist in Association with Profile Books Ltd. and PublicAffairs

Collection copyright Profile Books Ltd, 2016 Foreword, preface and individual chapters are copyright of the author in each case. Quotation from Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot on page ix reproduced by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd. These articles were originally published in Intelligent Life, the ideas, lifestyle and culture magazine from The Economist Group, which is now known as 1843 magazine.

First published in 2016 by Profile Books Ltd. in Great Britain.

Published in 2016 in the United States by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

The greatest care has been taken in compiling this book. However, no responsibility can be accepted by the publishers or compilers for the accuracy of the information presented.

Where opinion is expressed it is that of the author and does not necessarily coincide with the editorial views of The Economist Newspaper.

While every effort has been made to contact copyright-holders of material produced or cited in this book, in the case of those it has not been possible to contact successfully, the author and publishers will be glad to make amendments in further editions.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at Perseus Books, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com.

Text design by amanda.brookes@brookesforty.com

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016946360

ISBN 978-1-61039-681-3 (EB)

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

E3-20180410-JV-PC

Foreword

M useums are the places in which we can discover the past, reflect on our understanding of the world and gain insights that will guide us into the future. It was T. S. Eliot who reminded us that

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

and that our understanding of the past should be altered by the present, as much as the present is directed by the past.

In the last fifty years, attendance at museums in Europe and America has grown significantly, in part as a consequence of mass tourism. Museums have grown in number and in size and our appetite for spectacle and experience, as well as content, has been fed by dramatic new buildings. Frank Gehrys Guggenheim Museum Bilbao established a new model in 1997 and has since stimulated the ambition of small towns and cities across the world.

And yet, as we learn from the essays in this volume, size is rarely important except in the negative. When the writer Orhan Pamuk created his Museum of Innocence in Istanbul in 2012, following the publication of his novel of the same name in 2008, he wanted to demonstrate his belief that museums should be modest, of human scale, above all personal. In The Innocence of Objects, his manifesto for museums, he wrote:

big museums with their wide doors call upon us to forget our humanity and embrace the state and its human masses. The ordinary everyday stories of individuals are richer, more humane and much more joyful It is imperative that museums become smaller, more individualistic and cheaper. This is the only way that they will ever tell stories on a human scale.

Very few of the writers in this anthology embrace the experience of the large or the encyclopaedic museum. This may reflect the circumstances of an invitation to write a short, personal reflection on museums. However, it undoubtedly also discloses a widespread feeling that the most rewarding museum visit is one which involves communion between the viewer and a single object. When I stand in a room before a sculpture made in the fifth century BC, a painting made 500 years ago or a film installation by a living artist, nothing stands between me and the original maker. I feel the form and weight of the object in a shared space, the vibration of colours on the canvas, the sweep of the brush, or the contour of the line on the sheet of paper. These are objects made by another human being, recording his or her perception or sensation of the world, his or her beliefs, transmuted into our own time. It is this intensity, not available through the internet (even though Googles large magnifications of the details of great masterpieces have undoubted allure), that drives us to become a witness to human creation in the museum. The experience of observing and sometimes even holding an object is visceral, haptic and spatial. We situate ourselves in space and in time through the vision of another creative being. Cumulatively, museums offer thousands of small and large epiphanies.

We may also observe that few writers here have chosen to write about the most celebrated museums in large cities. The act of seeking out a distant, small museum can heighten the appetite and the experience in a form of pilgrimage. Small museums are frequently places in which we can withdraw from the pace of everyday life to examine ourselves, or explore the vision of others. They both demand and afford time for reflection and contemplation. In a world dominated by commerce and commodity, by fashion and novelty, museums have become places where values endure. In a society in which a sense of community or common space is now more rare, they provide a location for shared experience. The museum can be a platform for the expression of views and can offer insights into the way in which culture both responds and contributes to changes in society. In the twenty-first century the best museums will create space for conversation, debate and the exchange of ideas, as well as for instruction. Like universities, they can test hypotheses, but they can also attract the kind of broad public that generates a sense of trust and community rare in academic institutions.

It is perhaps surprising that so few of the essays here focus on the experience of the building itself, given the attention paid to museums by leading architects in the nineteenth and in the late twentieth centuries. Alan Hollinghursts visit to the Thorvaldsensmuseum in Copenhagen is an exception, but in general writers record their relationship with objects rather than with buildings themselves. Nevertheless, as museums become places of congregation as well as places of contemplation, the form of buildings will inevitably evolve. There will be a shift in the balance between space for looking and space for social engagement. In the past 50 years we have already seen significant change through the introduction of classrooms and lecture theatres and later of large shops, restaurants, cafs and event spaces. In the next 20 years, there will be a demand for rooms in which seminars, debates, conversation and practical work can occur. Learning will not be confined to the classroom or the auditorium, but will take place throughout the building, moving us forward from palace to forum: a democratic arena in which we can all learn from each other, from our present and from our past. That said, the unique experience of viewing objects and works of art in close proximity will remain the touchstone of museums. It is this experience which fuels the imagination of so many writers, and it is our privilege to share their insights on the pages that follow.