THE WORLD IN CONFLICT

Over the course of a journalistic career that began in the Middle East, John Andrews became The Economists most experienced foreign correspondent, with postings in Europe, Asia and America. Before joining The Economist, he wrote from and about north Africa and the Middle East for the Guardian and NBC News, interviewing personalities such as Muammar Qaddafi, Yasser Arafat and Ezer Weizman. He is the author of two books on Asia, co-author of a book on Europe and co-editor of Megachange: The World in 2050 (Profile Books, 2012).

THE WORLD IN CONFLICT

Understanding the worlds troublespots

JOHN ANDREWS

The Economist in Association with

Profile Books Ltd. and PublicAffairs

Copyright John Andrews, 2015

First published in 2015 by Profile Books Ltd. in Great Britain.

Published in 2016 in the United States by PublicAffairs, a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

The greatest care has been taken in compiling this book. However, no responsibility can be accepted by the publishers or compilers for the accuracy of the information presented.

Where opinion is expressed it is that of the author and does not necessarily coincide with the editorial views of The Economist Newspaper.

While every effort has been made to contact copyright-holders of material produced or cited in this book, in the case of those it has not been possible to contact successfully, the author and publishers will be glad to make amendments in further editions.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail

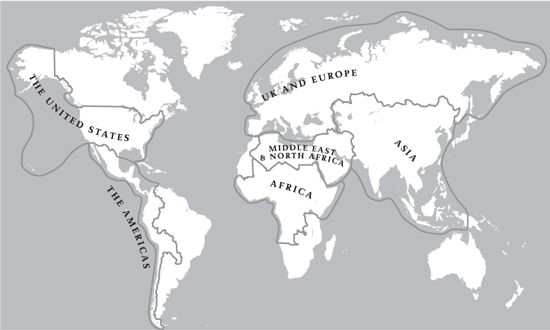

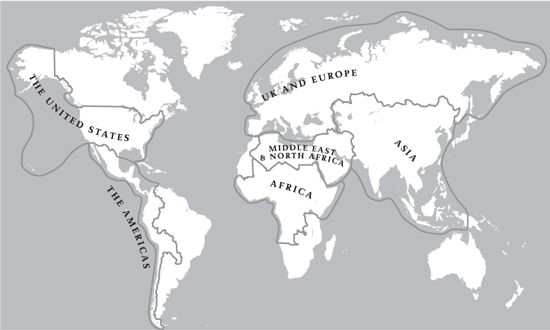

Maps by Martin Lubikowski, ML Design

www.facebook.com/makingmapswork

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015956502

ISBN 978-1-61039-618-9 (EB)

To Mika and Sam, in the vain hope that they will grow up in a world without conflict.

Geographical regions covered by individual chapters

An explanation

THE WORD CONFLICT can be applied to everything from a playground squabble to the second world war. For this book it means a difference of opinion between nations, peoples or political movements that involves the use of deadly violence. My criterion is that the conflict, no matter how distant its origins, should still be happening today (which is why, for example, there is only a passing reference to the wars that broke up Yugoslavia at the end of the last century).

There is a sobering number of conflicts that satisfy my criterion, from the unresolved civil wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to the secessionist violence in India and the Philippines. Does the violence meted out by organised crime meet my criterion? Not when the criminals are the Russian mafia. But in the case of Latin America, conflicts involving the drug cartels threaten the state itself and the violence by both cartels and state is easily extreme enough to qualify.

Nonetheless, on the basis of cause and effect, I have tried to place every conflict in its historical context. I have also tried not to take sides: violent conflicts arouse passions, certainly among the participants and often among outsiders (the ArabIsraeli conflict is an obvious example), but I hope I have been impartial.

As makes clear, conflicts can have many, often overlapping causes, which makes it difficult to catalogue them by categories such as religion, race, territory, resources or ideology. The simplest solution is surely to categorise them by geography and country, even though many conflicts, especially in Africa and the Middle East, cross national boundaries.

The best example of this defiance of national frontiers is the rise of violent Islamism. Much of this can be traced back to the cold-war era in which the West supported Muslim mujahideen from the Arab world in their ultimately successful fight to expel Soviet troops from Afghanistan. As is clear from this books chapters on the Middle East, Africa and Asia, the Islamist movements of today whether in Algeria and Mali or Pakistan and the Philippines often have their roots in the Afghanistan of the 1980s.

Violent Islamism also marks an upward tick in the otherwise downward trend of conflict in the wake of the second world war and, especially, the cold war. As wars between states almost disappear, civil wars and insurgencies many with an Islamist flavour are taking their place and so mocking our recent fantasies of universal peace and the triumph of democracy.

Should we therefore surrender to a fatalistic gloom? This guide to the worlds conflicts may well bring to mind the view of Mahatma Gandhi:

What difference does it make to the dead, the orphans and the homeless, whether the mad destruction is wrought under the name of totalitarianism or in the holy name of liberty or democracy?

But Gandhi was speaking in an age horribly scarred by the first and second world wars. Though his words are still relevant, at least as shows todays many conflicts are creating fewer corpses and fewer orphans.

Lastly, Arabic transliteration is fraught with difficulties (see ). I hope I will not offend purists by frequently deviating from classical correctness.

John Andrews

October 2015

The reason why

IF EVERY EIGHT-YEAR-OLD in the world is taught meditation, we will eliminate violence from the world within one generation. Or so the Dalai Lama has claimed in one of those comforting quotations that go viral in a world of social media. There is, of course, no possibility that His Holinesss condition will be fulfilled. If the present is a guide to the future, it will be one of frequent conflict confirmation that violence is part of the human condition and that men and women will continue to take up arms in pursuit of their goals. As Carl von Clausewitz, a Prussian general with a more realistic view of humanity than the Tibetan leader, put it: War is an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.

The evidence is everywhere. During the 21st century, which is not even two decades old, the US and its allies have invaded Iraq and Afghanistan; Russia has been at war with Georgia; the UK and France have combined to help topple a regime in Libya which then succumbed to fratricidal anarchy. These are just a few of the more bloody conflicts pitting nations against nations. Others are less bloody, but still dangerous: for example, the nervous stand-off between India and Pakistan in Kashmir, where troops from both sides threaten each other occasionally with fatal results across the line of control drawn as long ago as 1972 in the snow-bound Himalayan and Karakoram mountains. In East Asia, North and South Korea may not be in direct conflict, but the nuclear-armed totalitarian north and the capitalist, democratic south have yet to conclude a peace treaty to put a formal end to a war that began in 1950. Elsewhere in the Pacific region, maritime and territorial disputes entangle China, Taiwan, Japan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam and Brunei, and no one can be truly confident that these arguments, over bits of rock or expanses of ocean, will not lead to armed conflict whether by design or by human error.

Next page