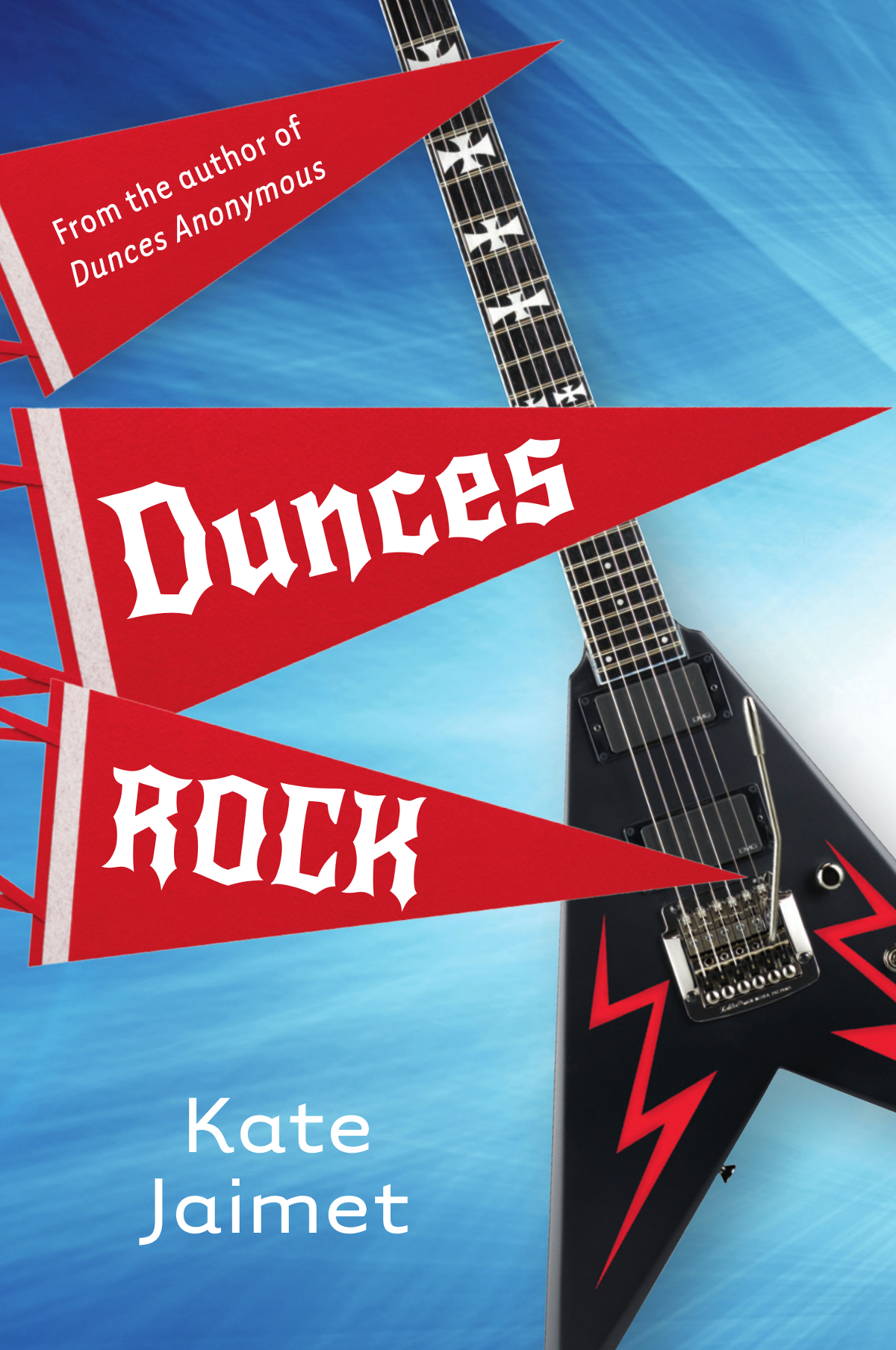

The electric guitar sat on a lopsided orange-and-gold sofa on the curb at the end of someones driveway. Its glossy body gleamed in the wintry late-afternoon suna jet-black arrowhead blazing with two red thunderbolts. In the cold January light, its six silver tuning pegs winked like the crystals in the snow that covered the front lawn. Maybe it was a signa signalto Wilmot Binkle as he trudged down the sidewalk on his way home from school.

Wilmot was walking home alone, as usual. He was dragging his feet, as usual, because he knew that when he opened the front door, there would be a long list of mathematical problems waiting for him to solve before his father got home from teaching at the university.

A kid should get a break between school and homework, Wilmot thought. He kicked a chunk of ice down the sidewalk. There should be a law or something.

At that moment, the guitar leaped into view, and the sight of it ripped through Wilmots gloom like the opening chord of a rock-and-roll anthem.

An electric guitar.

What was it doing there, perched on the tattered upholstery of that ugly, three-legged sofa? Was it possiblecould it even be possiblethat someone had thrown the guitar into the trash? Though still half a block away, Wilmot was drawn to it by an inexorable force.

Creeping closer, Wilmot feared that at any moment the guitar might vanish, might turn out to be nothing more than a figment of his imagination. But no, it was real. As he approached it, Wilmot could see that the guitar had been played by someone until it was almost worn out. Five of its six strings were gone, and the black lacquer of its body was scratched and chipped.

I can replace the strings, Wilmot thought. I can fixthe scratches with a little bit of black paint. If only theguitar could be mine.

Wriggling his right hand out of its woolen mitten, which stayed stuck in his jacket pocket, Wilmot reached out to touch the instrument. His fingers stroked the cold, shiny surface. He plucked the one remaining string.

Hey, little dude!

Wilmot jumped. He spun around, stumbled backward, fell over the arm of the sofa and landed on the frozen sidewalk, on top of his enormous backpack filled with heavy textbooks.

Im sorry, I didnt mean to, Im really sorry! Wilmot spluttered. Above him loomed a tall long-haired teenager.

The teenager reached down and yanked Wilmot to his feet.

Chill, he said. I didnt mean to scare you.

Despite the cold, Wilmot felt the palm of his hand breaking into a sweat. He yanked it out of the teenagers grip and stuffed it in his pocket. His eyes turned toward the guitar.

Is itis it yours? he gasped out.

That old guitar aint mine to keep, little dude, said the teenager. It was mine to play for a while. Yknow?

Wilmot didnt know. But he didnt want to admit that he didnt know. He wasnt sure whether the teenager was mad at him. The guy didnt look mad, but it was hard to tellhe had metal piercings sticking out of his nose and eyebrows, and he was wearing a T-shirt with the word Megadeth on it. Wilmot didnt want to take any chances.

I thought someone put it in the trash, he said.

Not the trash, little dude. I put it out so someone would find it. A rebel vigilante. A midnight rambler. A jukebox hero. Now do you get it?

Wilmot still didnt totally get it. But he grasped the part about someone else finding it. Someone elsemaybe himself.

Could Icould I have it?

Little dude! said the teenager. Thats what Im trying to tell you.

The teenager picked up the guitar and held it out to Wilmot. Wilmots fingers curled around the cold fretboard. He cradled the body in the crook of his right arm. The guitar felt as though it belonged thereas though it had always belonged there.

He looked up at the pierced face of the teenager.

Now that he wasnt so nervous, Wilmot thought he recognized him.

Lester?

Shh! The teenager glanced up and down the street.

Wilmot lowered his voice. Werent you mybabysitter? Like, when I was a little kid?

Yeah. That was before I got thishe pointed to the spike in his eyebrowand thishe touched the ring in his noseand thishe stuck out his tongue and waggled the metal stud pierced through it. And I changed my name to Headcase.

Oh. Good name, said Wilmot. He was pretty sure his dad would disown him if he ever changed his name to Headcase. And thanks for the guitar. Butwhy?

Come with me, little dude, said Headcase. Ill show you.

He turned and loped down the driveway toward a tall red-brick house. Wilmot followed him, excited and nervous. He climbed the stairs of the rickety front porch, past a snow-dusted bicycle chained to the wooden railing, and watched as Headcase opened the front door, took a key out of his pocket and opened a second, inner door marked Apartment 1-A.

Headcase stepped inside. Grasping the guitar, Wilmot followed him.

The front hallway of Apartment 1-A smelled of stinky running shoes, old wallpaper and Kraft Dinner. To the right, a doorway opened into a large room with a fireplace in it, which looked like it was supposed to be a living room. The room was bare except for a mattress on the floor and a pile of dirty laundry, and some bedsheets hung over the windows instead of curtains. The teenager kicked aside a pile of junk mail from the hallway floor, opened a door to the left and led the way down a narrow flight of stairs to the basement.

Wilmot followed.

The basement smelled of even stinkier running shoes, mixed with greasy pizza boxes and grungy carpeting. But in an instant, Wilmot forgot about the odor. For in front of him stood the most amazing array of rock n roll gear that he had ever set eyes on.

Wow! he breathed. What is all this stuff?

Harmon Kardon receiver, authentic 1974 Pioneer turntable with diamond-tipped needlemy dad gave me thatsix-CD changer, equalizer, reverberator, subwoofer, JBL speakers, Hackintosh computerI built it from scratch from parts I got off the Internetwebcam and MIDI keyboard. And thisHeadcase turned to a wall lined with plastic milk crates, stacked sideways and crammed with hundreds of CDs and vinyl recordsis my awesome collection of Rock Through the Ages. Everything from Chuck Berry to Green Day and beyond. I got it all right here, little dude. But what you really came to see is this.