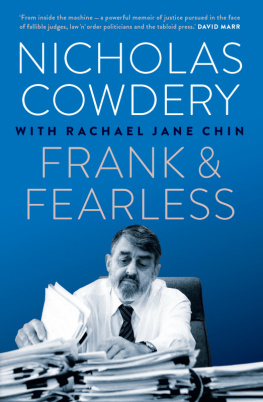

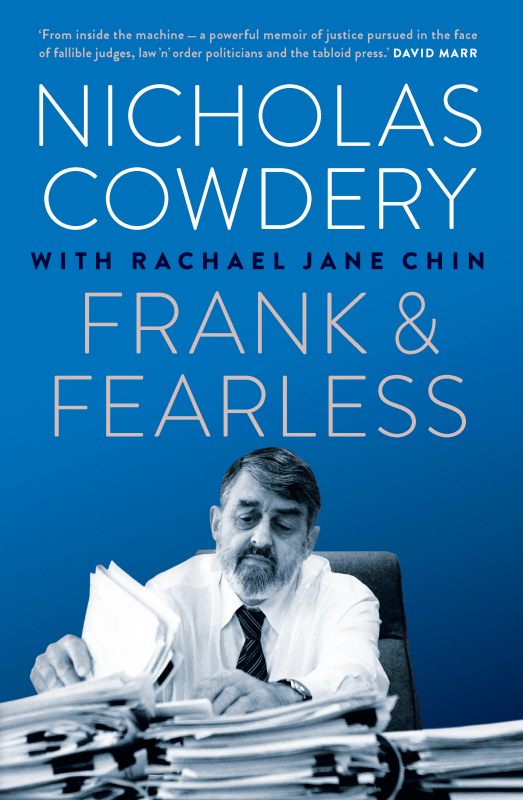

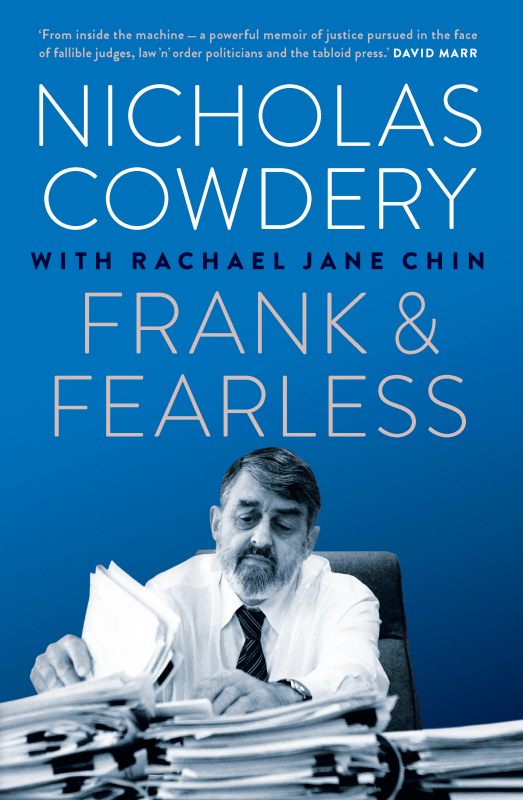

FRANK & FEARLESS

NICHOLAS COWDERY AO QC was the Director of Public Prosecutions for New South Wales (known as the DPP) from 1994 to 2011. Previously he had been a barrister since 1971, working in Papua New Guinea and at the Sydney Bar. Since 2011 he has focused on helping developing countries improve the rule of law and protect human rights, especially through professional prosecution systems, and giving advice on how to maintain the rule of law and improve criminal justice in Australia. One example of this is his work with a number of organisations dedicated to reducing Indigenous over-representation in the criminal justice system. Nick is a University of New South Wales visiting professorial fellow and adjunct professor at the University of Sydney.

RACHAEL JANE CHIN practised as a lawyer before becoming a non-fiction writer. Her first book, Nice Girl: The story of Keli Lane and her missing baby Tegan, was published in 2011. From 2002 to 2004 she was employed as a journalist by the Australian Financial Review. Her website is

NICHOLAS COWDERY

WITH RACHAEL JANE CHIN

FRANK & FEARLESS

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Nicholas Cowdery and Rachael Jane Chin

First published 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

ISBN: 9781742236377 (paperback)

9781742244617 (ebook)

9781742249100 (ePDF)

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Peter Long

Cover image 25 August 2009: Sydney, NSW. Director of Public Prosecutions,

Nicholas Cowdery QC, at his office in Sydney during an interview with The Daily Telegraph. Photograph by Cameron Richardson. Newspix

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The authors welcome information in this regard.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

For 16 and a half years, from 1994 to 2011, I was the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) for New South Wales. The DPP is the chief prosecutor, and a gatekeeper for the criminal justice system. He or she decides if, when and how a police investigation into a serious criminal offence is to be tried in a court of law.

The role of DPP is extremely stressful. In addition to managing an office of hundreds of professionals, it involves being immersed in the very worst and saddest of human behaviour, making sometimes extraordinarily difficult and often unpopular decisions, dealing with a lot of attention from the media, and dealing with pressure from public figures, particularly politicians, that is not usually helpful or necessarily fair.

When I walked through the office door each day, I knew that almost every decision I made would make somebody unhappy. If I decided to prosecute someone, he or she would be unhappy. If I decided not to prosecute, a victim or a police officer or both would be unhappy. If I decided to appeal against an inadequate sentence, the prisoner would be unhappy; if I declined to appeal, the law-and-order brigade would erupt. Almost any decision I made could make the media, a politician, or both, unhappy for a multitude of reasons, or for no good reason at all. Members of the community would express their unhappiness with what I did, individually or in groups. Excessive demands upon staff were always a cause for angst.

This all went with the job, however, and any concerns about such effects had to be suppressed. The DPPs office will always be an unusual working environment and not attractive to many but those who work there render great service to the community. I had chosen to work with them and I thoroughly enjoyed it (for the most part).

In my previous career as a barrister practising largely in crime, I was familiar with the work of the crown prosecutors and the role of the DPP, but I was unprepared for both the managerial role and the level of active outside attention the position attracted. When I was appointed DPP by NSW Premier John Fahey in 1994, I expected the role to be an interesting and stimulating challenge and the high point of my career. I was willing to take on the responsibilities of the office and, if I could, work improvements in the criminal law and its processes. I didnt realise how controversial that modest aim could become. I knew that my predecessor had carried out reforms, but in a style that did not attract public attention. I quickly formed the view that I should do it differently, explaining to the community as I went the reasons why changes should be made for its benefit. I was temporarily blind to the politics of that course.

During my tenure, the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP) had a staff of around 300, rising to over 600. That included the senior crown prosecutor, deputy senior crown prosecutors, crown prosecutors, lawyers and administrative staff located in ten offices around the state. I worked closely with many of the prosecutors, some of whom featured prominently in the media because of the cases they conducted.

In the course of an average year, the ODPP had up to 18 000 cases before the courts and in preparation by the end of my tenure. I was not involved in all of them, but the more serious cases either because of their nature (e.g. involving a death or serious abuse), public profile, legal complexity or contentiousness would all come to me for final decisions at various stages of prosecution. It was always satisfying to have a conviction in a case where I thought that should be the just outcome, according to the law though as this book shows, some cases and convictions did pose larger questions of whether the law needs reform to better serve the interests of justice.

This book shows what the rule of law looks like in the prosecutors office, and describes some of the most significant cases that came across my desk. A properly functioning criminal justice system involves the DPP and having to deal with situations where there are usually no winners and no limits to the awfulness.

Why would anyone in their right mind put themselves through such pain? Former Justice of the High Court Michael Kirby AC CMG once summed up why the criminal justice process appeals to legal professionals:

No other branch of the law is so important. It is where our commitment to fair trial and the rule of law are tested every day, in courts throughout the nation. It is where fear of wrongdoers intersects with respect for basic human rights.

Ever since humans began to live together, we have needed rules for our conduct. Rules allow us to live together harmoniously and to have ways of resolving disputes. Those rules are often enacted in our laws. Inevitably criminal laws intersect with other systems of rules based on morals, ethics, religion and philosophy. Criminal laws apply to all of us they cannot be evaded or applied selectively but those other systems, and even the criminal laws, sometimes require choices to be made in their application.

Next page