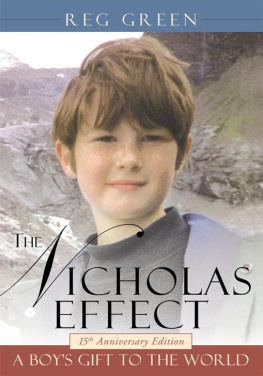

Finding an adjective that has not been used to describe Reg Greens story presents a problem. Superlatives come to mind but, in todays overhyped world, superlatives have been devalued until you dont trust them anymore. Then comes The Nicholas Effect , earning every superlative you care to attach.

Jim Belshaw, Albuquerque Journal

This luminous story of extraordinary people who made a world-changing decision, is filled with grace and, unexpectedly, joy. The Greens have shown us, as they say in baseball, the way to be.

Killian Jordan, Senior Editor, LIFE Magazine.

The Nicholas Effect is the familys latest effort at taking the worst that life has to offer and transforming it into something sweet, noble and lasting.

Richmond Times-Dispatch

Green tells, with the apparent simplicity of a great writer, a story that would put a lump in the most cynical writers throat.

Il Giornale , Italy

A beautifully written book.

San Francisco Examiner Magazine

This book shows the power of transplantation to save lives.

Katie Couric

The Nicholas Effect

A Boys Gift to the World

Reg Green

Booktango

Bloomington

Booktango

1663 Liberty Drive

Bloomington, IN 47403

www.booktango.com

Phone: 877-445-8822

2009 Reg Green. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the written permission of the author.

ISBN: 978-1-4689-0015-6 (ebook)

Contents

The Nicholas Effect was first published by OReilly and Associates of Sebastopol, California in 1999. I want to thank them for that and for their kindness in allowing this new edition to be brought out. It has not been changed in any way, except for the addition of an afterword on page 251. I am taking this opportunity to thank AuthorHouse also for so generously supporting this project throughout.

To Nicholas

for all that he was,

all that he might have become,

and all that he still is

to his family and friends.

ONCE UPON A TIME..

Now lets get this straight, I said to myself. He was a hero, he was a real person, and weve been in places where he lived. But he wasnt American, he wasnt British, not French, not Roman, not Greek. Weve read about him but never met him. Out loud I said what I always regretted. I give up.

Bonnie Prince Charlie, said Nicholas, my son, with quiet satisfaction.

You said he wasnt British.

No, I said he wasnt English. It was true, thats what he had said. I could have kicked myself. It was the last game he ever played. Two hours later he was shot in the head by car robbers on the road to Sicily and never regained conscious ness.

This last win was typical of him. He chose well, answered carefully, and had a lot of fun doing it. He never cheated. He was a joy to play games with.

It seems fitting that this radiant little creature, just seven years old, should have touched the hearts of millions of peo ple all over the world.

A LONG JOURNEY STARTS

THE FOUR-WEEK VACATION , the longest wed ever taken, had been planned for months, a combination of hikes in the Swiss Alps and the color and history of southern Italy. Switzerland was my responsibility and I had a few routes marked out in the guide books. But theres a limit to how much you can anticipate a hike by letting your eyes do the walking.

Not so for the Italian part. Just about every night that summer either Maggie, my wife, or I read stories to Nicholas about the classi cal world, the other parent going through The Tales of Amanda Pig and such with his four-year-old sister, Eleanor. Greek gods, Roman soldiers and ancient buildings, what clothes they wore in Pompeii, how quickly the legions could move, how they kept food cool in hot weather, where they fought, this was the staple fare of those quiet sum mer nigh ts.

Nicholas thrilled to stories of heroes risking their lives for the com mon good, was puzzled by the cheap tricks of gods who ought to have known better, and laughed at Cupids mischief. He was pained by the story of Persephone, imprisoned all winter in the underworld. When the blinded Cyclops ran his hands over the sheep Ulysses and his men were clinging to, I thought hed burst. He seemed to grasp the mean ing underneath the stories: the fatal flaw, the good and bad in us all, lifes fragility, but its higher purposes too.

All this was his way of life. His core games were dressing up and doing great deeds as St. George of England, a pioneer on the Oregon Trail, or his most enduring role, Robin Hood. All were supported by the props that imagination and needle and thread could supply. The broom handle was the quarterstaff, the sign of Ye Olde Blue Boar Inn was tacked to the bedroom door, the longbow came from Kmart. Then Robin and Maid Mariansometimes two Maids Marianand a pickup group of merry men would set off to conquer evil, often squab bling among themselves about what they would do with it when they met it.

At parties we held, he would put on his best clothesblue blazer, light-colored shirt, clip-on bow tieand with a small pad of paper and stumpy pencil take drink orders in illegible writing. On hikes near our home in Bodega Bay, California, we would keep one eye open for sneak attacks by the enemy army or, on the beach, their navy.

Our local library allows thirty books for each card and we had three cards. My memory of the first days of the summer of 1994 is of Maggie bumping up against the borrowing limit with every possible variation on the Italian scene. I was allowed one novel and she got one of those pulp love stories. (Doesnt she get enough romance at home?) For Nicholas and Eleanor, there were a few books like Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs, a story about a town whose food comes with the weatherovercooked broccoli one day, a record-breaking fall of pasta another. But the rest of them were Greek myths for children, Roman history for children, maps of the ancient world for children, junior ver sions of the Odyssey and the Aeneid, stories of travels in Sicily, archae ological digs, famous buildings, and picture books of modern Rome.

Maggie found a Roman cookbook and we planned a banquet, but none us could stomach the fish with honey dish. Nicholas only con sented to eat at all that night when we told him spaghetti was Julius Caesars favorite meal. My main concern was overdue fines: think of ninety times twenty-five cents a day. The reading itself was a delight. We read to the children, read to ourselves, swapped tales over meals. On one long car journey we took that year, Nicholas wanted so many stories read to him from DAulaires Book of Greek Myths that my spells as a passenger in the back seat with him are a complete haze. But not, as it happens, to him. Weeks afterward he would remind me, for example, that the echo we heard was a girl who had talked too much and been punished by only being able to repeat other peoples words.

We all loved traveling. Ive done a lot on my own, and as a family wed walked on volcanic craters in California and the Icefields Park way in Alberta, seen waterfalls as different as Niagara and Frank Lloyd Wrights Fallingwater, canoed in Canada and rafted in Idaho, seen Indian rain dances in New Mexico and immigrants toys on Ellis Island, and spent long, sticky days in both Disney World and Disney land. In Europe, Nicholas had stormed the invasion beaches in Nor mandy, hiked on the shoulder of the Matterhorn, visited Sleeping Beautys Castle in the Loire Valley, and climbed with us (when no one was looking) to the top of the lighthouse on the extreme northwest tip of Scotland, the area where my mothers ancestors, the McKays, have lived since the Middle Ages.

But of all places abroad, he liked Italy bestthe theatricality of the settings, its exuberance, and its uninhibited love of children. For his age, hed seen a lot of it. Hed splashed in the sea at Portofino, taken walks around the melodramatic peaks of the Dolomites, and got his socks wet in Lake Maggiore. Hed tramped around Pisa and Florence and Verona. Wed all been together in Asolo, the hill town where Browning wrote Gods in his Heaven, alls right with the world, and Id say that for us, sitting under the awning of a restaurant on that hot, still day, and chatting quietly amongst ourselves, it was the literal truth. Hed marched around the giant chessboard in the town square at Marostica, where people dress sumptuously as knights and castles and pawns to reenact classic games. At six years old, he was silenced by the power of the mosaics in Ravenna. He always said his favorite city was Veniceafter Bodega Bay. But this was the first time he had been as far south as Rome, and with a mind crammed with gods and heroes, he was on edge to see it all.

Next page