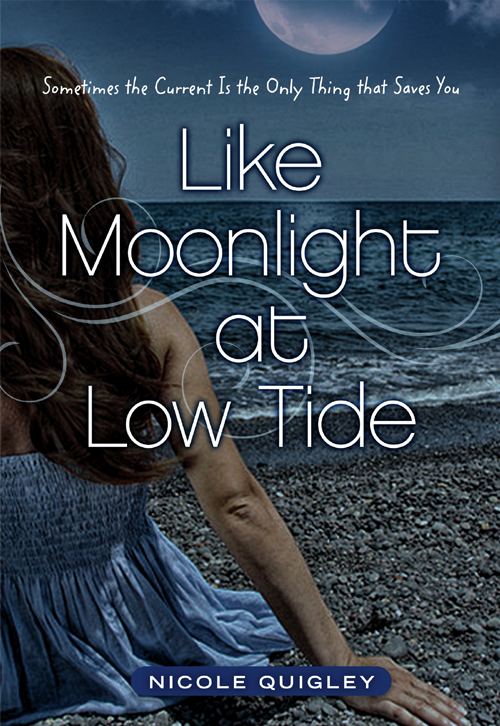

P eople never ask me the right question when they ask me what happened the beginning of my senior year. They always ask what his last words were. They figure he would have had great ones, the kind that would haunt a girl and echo off of empty lockers long after graduation. They wait breathlessly for me to describe the moment he jumped off the boat and into the glass-topped Gulf, cutting the ribbon of moonlight on the surface with the white of his arms.

Surely he was trying to kill himself, theyd say. Why else would he leap into the water without the hope of rescue?

And so I tell them what they earnestly hope to hear. How I searched desperately for the bob of his head in the water. How I jumped in myself, swimming fifteen feet until I felt the absence of the boat behind me, the vessel leaning away from the edge of the bay and into the dark, magnetic waters of the deep. They want to hear how hard it was to make my way back to the boat, and how, by then, the storm was beginning to unleash its rage. They want to hear how I scoured the cabinets for a radio and failed. How I searched for a flare gun but found no rescue.

And when I tell them of all of these things, they never askand I never mentionthat I did all of them in complete silence.

The truth is, he said nothing before he jumped. And I never called his name, not once. I knew that he had plunged into that water so that he could not be found.

When the sheriff pulled his boat next to mine, he spoke the first words I had heard in hours. He lifted me from beneath the captains console, where I had waited with my knees tucked under my chin. That was the evening Hurricane Paul swept through our state.

This story is not about suicide. But you should know that when I was seventeen, the only boy who ever called me by my full name took his own life. It was the first time I ever saw a mistake that was permanent, that couldnt be undone with whiteout or atoned for with an after-school detention. Nothing else I do for the rest of my life will ever be able to change this fact.

This story is actually about three boys. One who loved me. One who couldnt. And one who didnt know how.

My name is Melissa Keiser, and I was raised on Anna Maria Island, Florida.

The best description of the place I can provide you is a temperature: eighty degrees. It is not always eighty degrees on the island, but the humidity looming off the white foam of the Gulf of Mexico combined with the faint, sickly sweet emission from the orange juice factory always seems to make the place feel like its been wrapped in a warm blanket, just soft enough to make you feel safe or sleepy, but always feel slow if you tried to move too much within its folds. In truth, it is the most beautiful beach town I have ever seen. And then the breeze comes and reality finds you hiding behind a sand dune.

The Anna Maria Im writing of is not the same island that you would see if you went online and searched the images posted by Yankee tourists and gray-haired Canadians. Those visitors love the island as much as anyone who has never suffered here can. They post pictures of things like starfish and sandcastles and pelicans at sunset. They marvel at the brightly colored flowers that seem to grow from the ditches like weeds, and the waist-high herons, and the restaurants grilling grouper underneath tin-roofed sun decks. This is, after all, a place overflowing with such abundant beauty that its residents actually chased off native, jewel-colored peacocks to the neighboring cities because it deemed them a nuisance. Only an island sure of its place among beach towns could afford to do such a thing without regret.

But pictures of these things dont show what life was like for me or for the others who walked these streets that year. To the tourists, we are points of curiosity. They wonder what it would be like to raise their children in a place where the speed limit is twenty-five and the town shuts down for the high school football game. And we oblige to tell them and show them how to pick up crabs with their bare hands. This is what happens when youre surrounded by people who visit for two weeks at a time, intent on happiness, always reminding us of how wonderful the island is compared to where they live, because where they live is lucky to have a city park and a tree that has kept its leaves. But when the conversation ends, we never make it into their pictures.

In the time since I was a child, those tourists have slowly razed the neighborhoods of my youth, house by house, in order to build pink, tall homes in their place that people like my family could never afford to rent. But that was never the point. Now, their new winter domains sit empty six months out of the year, while locals move to the concrete mainland in search of cheaper rent. It is an odd thing, to love these visitors and to depend on them for supper, while at the same time knowing the more who come will mean less room for us.

But I am writing of the island not pictured on Google, the one that still harbors the necessary number of the working class who have found a way to make a home on a seven-mile stretch of paradise without the rich folks noticing.

When my mother moved us back in the winter of my junior year after spending three years up north, it felt like a flood was coming and I had forgotten how to swim.

When are you coming home? I regretted my tone instantly because I knew exactly what it was going to get me.

Its none of your business, Denise shouted into the phone to mask the sound of the band starting up in the background. I left ten dollars on the kitchen table. Go to the store and buy some subs for you and your sister. My mother was certain that ten dollars could solve most of my complaints, whatever they were. She never used the same tactic with Robby. My older brother never had to babysit, and he was never home long enough for us to consider that he would.

I dont want to have to be here all night, Mom.

You dont have a choice, Missy. I gotta go. The band started its rowdy thump in the background as the phone clicked off. Maybe tips at the restaurant would be good tonight.

I turned to my sister in resignation. Its you and me again, Crystal. Put on your shoes. Were going to get some dinner.

She struggled with the strap of her sandal until I squatted down and gently brushed her hands away. These things were always easier when I fixed them myself. She was too small to help with much of anything, and I was certain she wouldnt be growing anytime soon. She hadnt grown in a year. This would be alarming to a doctor, if we could afford one, considering she was only seven.

Wrong way, I said, quietly. I tugged her hand in the other direction so we would walk down Gulf Drive instead of our neighborhood road, where Tanya Maldonado would have surely spotted me from inside her climate-controlled home. I hadnt seen Tanya since middle school, since before my mother made us chase her boyfriend Doug to the gray hills of Pennsylvania.

And even though I had been gone for three years, I knew she would be waiting for me as if I hadnt missed a day. In middle school, she had found everything I did to be endlessly fascinating.