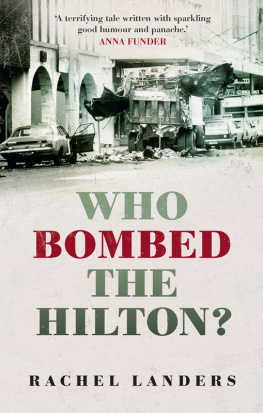

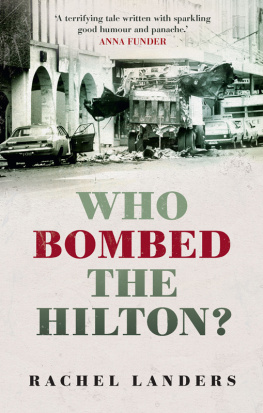

THE HILTON

BOMBING

EVAN PEDERICK AND THE ANANDA MARGA

IMRE SALUSINSZKY

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2019

Text Imre Salusinszky, 2019

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Lyric excerpt from Absolutely Sweet Marie by Bob Dylan. Copyright 1966 by Dwarf Music; renewed 1994 by Dwarf Music. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. Reprinted by permission.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Typeset in 12/15pt Bembo by Cannon Typesetting

Cover design by Philip Campbell Design

Cover images: Evan Pederick courtesy Frances Andrijich, and the

Hilton Bombing courtesy Fairfax Media.

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

9780522875492 (paperback)

9780522875508 (ebook)

For Charlotte and Alistair

CONTENTS

Part I

LOSING THE SELF

To live outside the law, you must be honest.

Bob Dylan

LIVING IN THE SEVENTIES

The Lord be with you, says the priest. He has a close-cropped moustache and goatee; hes neither fat nor thin, neither tall nor short, pleasant in appearance rather than striking. His manner is mild. There is nothing ingratiating or needy about himquite the contrary: he is slightly reservedbut even in his flowing white robes, he seems approachable. He is standing in a modest cream-brick church at Cannington, a blue-collar suburb in the south of Perth.

And also with you, respond his listeners. There are about twenty-five among the Anglican congregation at St Michael and All Angels this February Sunday morningthe first Sunday of Lent, 2012. Its a multicultural group that reflects the strong Philippine, African and Islander communities in the area. There is a majority of older faces in the pews. Soon, the priest will leave the altar and bring the blessed sacrament to one elderly man where he sits in his wheelchair.

In this season of penitence, waiting and hope: Lord, have mercy, says the minister. Penance, repentance, self-denial, wandering in the desert: these are the themes of the Lenten observance. Christ, have mercy, replies the congregation. Hear the commandments which God gave to Israel, says the priest.

Later, in his sermon, he will strike a literary note. As an example of what the desert means to Australians, hell talk about Patrick Whites novel Voss, telling his listeners that What makes the novel so powerful is its exploration of the role that the desert plays in the Australian psycheas a force to be reckoned with, an obstacle to be crossed and tamed, a void filled with fantasised treasure to be exploited, but also as an emptiness of almost mystical dimensions that both fascinated and horrified colonial society. He adds that the desert works as a sort of blank canvas that reveals most of all the unexplored depths of the human mind and soul.

The congregation may know a bit about Patrick White, or not. But how much do they know about their priest? Do they understand that many years ago he attached himself to beliefs that are the antithesis of the mild and moderate Anglicanism they are celebrating this Sunday morning?

Do they know the priest has broken the sixth and most dire of the commandments he invokes to them: You shall not murder? Do they know that he spent ten years wandering in a desert of his own guilt and self-loathing? Do they know this was followed by another decade locked up in jailwhen he was deemed too dangerous to be part of any normal communityon the other side of Australia?

The answer to these questions is, most probably, yes. The priest sometimes says hes glad of the internet, because he can assume that his flock has googled him and discovered that for three years in the late 1970s, he was an indoctrinated member of a group that committed acts of violence around the world. Hes glad this kind of research is available because he is not interested in concealing his past, and it relieves him of any periodic rite of disclosure.

If those in the church do know these facts, they dont appear discomfited. The priest seems to have an easy, relaxed relationship with his parishioners. In a few minutes, some will approach him for counsel. But now, as the service draws to a close, he reminds them of upcoming social events, asks for volunteers in various roles. These sausage sizzles and quiz nights may seem trivial alongside the existential themes of Lent, with its trials and tribulations in the desert. They seem even more so set against the absolutist themes that drove this mans life all those years ago, and that convinced him it was necessary and right to take the lives of innocent people.

Yet these social rituals are peculiarly comforting things, signs that one is a member of a normal community. After awful acts, though, can that ever happen? How far can you transgress normal social boundaries, then cross them again in the other direction, back to the fold? Christianity appears to set no limits on the journey back. The little booklet accompanying todays service quotes Psalm 25: Remember not the sins of my youth, nor my transgressions: but according to your mercy think on me.

Even so, a listener this Sunday, an outsider to Cannington and Christianity too, reflects that it must have tested the limits of the Church not just to forgive this lost sheep, but to make him a leader of his flock. Did they consider it risky? Or might they have concluded that such a mans experiences, for all the suffering they brought, have also brought him ways of responding to the wanderings and tribulations of others? Those experiences surely add some depth, today, when he talks to his parishioners.

In the desert, he tells them, everything that is non-essential gets stripped away and discarded. To survive in the desert, you need to get back to the basics of who you are and what youre about.

Early on the morning of Thursday, 16 February 1978, three days after the Hilton bombing, I stood on a street corner in the Melbourne CBD, awaiting a motorcade. Late the previous evening, on the Wednesday, Id been at work as the duty cadet at The Age when we heard the Indian prime minister, Morarji Desai, would be flying to Melbourne to visit the ailing former prime minister Sir Robert Menzies. The chief of staff, Neil Mitchell, called me over from the photo desk, where I was trying to keep a low profile, and told me to be on deck exactly seven hours later.

Given Desai was already assumed to have been the target of the bombingcorrectly, as it turned outhis sudden unannounced visit to Melbourne was a big story.

Deadlines were much later in those pre-digital daysdespite the fact that every page of the newspaper had to be set up using blocks of metal typeand we had no problem splashing Thursdays paper with the news, just as wed managed to get the bombing itself, which had occurred at 12.42 a.m., into Monday mornings paper. For some reason Ive never forgotten the stark headline that appeared above Michelle Grattans front-page story: Desai for Melbourne. Her copy captured the feel of that weeka security panic unleashed by the bombing that would leave Australia forever changed: