To my wife

PEGGY

the sure shield; the strong right arm; who never flinched even in the Darkest Hours

Contents

Not many people survive an air crash. I was one of the lucky ones who did. So were Sir Matt Busby and Bobby Charlton.

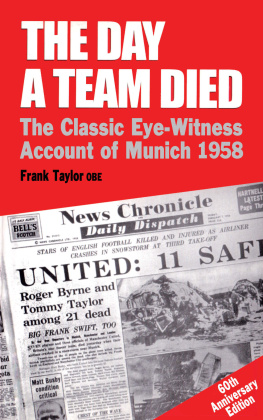

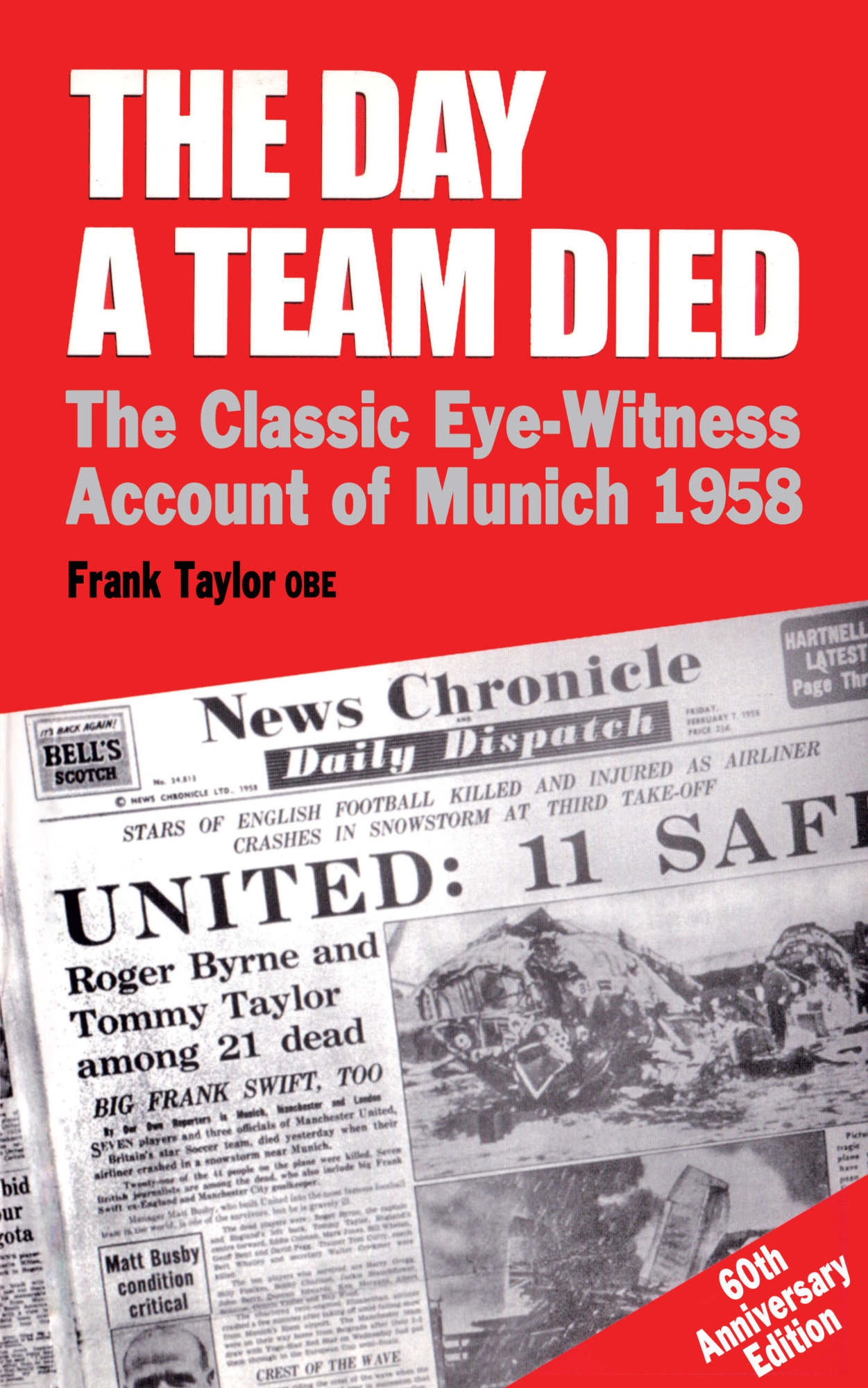

Twenty-five years have now passed since Manchester Uniteds young football team, returning in triumph from a European Cup tie in Belgrade, crashed at the end of the runway on Munich Riem airport, shortly after three oclock on the snowy afternoon of Thursday, February 6th, 1958.

Those of us who survived need no calendar to remind us of that tragic day, the saddest ever in British sport. The memories are inscribed upon our minds until the day we die.

I have been asked many, many times why it was that, after two attempts to take off had failed, we all trooped back on to that airliner without any signs of panic or protest, for that third fatal take-off attempt.

The answer is very simple. We were all anxious to get home to Manchester, and as everyone must know, pilots do not take any risks because their lives are just as much in peril as their passengers.

So we went back on board, the engines roared into life, and in 54 seconds 23 people had been killed and the football legend of the Busby Babes was destroyed for ever.

Yet it was not only Manchester United who suffered in this tragedy. Newspapers suffered, with eight of the best sports writers I have ever known killed. They were my friends, and I learned so much from them that I have tried to carry on their style and tradition.

Some present-day colleagues may think that I overstate the brilliance of the Babes because I was emotionally involved. Of course they are entitled to hold that view, although personally I do not think English football has ever completely recovered from the Munich Air Crash.

Walter Winterbottom, who was manager of the England team at that time, is still convinced England had the team to win the World Cup in 1958.

He has told me many times: You can never be completely sure of course, but I am in no doubt we had the players and the team spirit to win the World Cup in Sweden in 1958. We lost three key players in Roger Byrne, Duncan Edwards and Tommy Taylor in the Munich Air Disaster, and no international team can lose players of that calibre It was just a tragedy for English football.

Instead, the 1958 World Cup series brought glory to Brazil, and a 17-year-old wonder man named Pele. But I often wonder, would it have been a different story for Brazil, and especially for Pele, had he been playing against our superstar Duncan Edwards, who was himself only 21 but already an established international?

Years, they say, lend enchantment, but I am in no doubt that Duncan Edwards was the best English player since the end of World War II. It is a view shared by the former England captain Billy Wright. And I can think of no better way of describing the impact Edwards had on a game than Bobby Charltons summing up:

Compared to Duncan, the rest of us are just like pygmies. He had the lot

There is no doubt that the English game was never quite the same after Munich. The Babes were brash, brilliant, and attack-minded. Their obliteration coincided with a dramatic change in tactics, with almost every team playing a largely defensive game, so that young people now watching the game have never known anything different.

I hope young football fans of today may find something of interest in this book. I started to write it from my hospital bed in Munich, typing laboriously with one hand, because I wanted to leave some kind of lasting memorial to the Babes and my newspaper colleagues, and also because most of my life has been spent in front of a typewriter, and this was wonderful therapy.

Now, 25 years later, I have changed some parts of the original manuscript to bring the story up to date, although I saw no reason to change those parts of the narrative dealing with the air crash itself, because those words were written when every aspect and nuance of the tragedy was still fresh in my mind.

It is a story not exclusively about a football team, because this air crash went deeper than that. I wanted to pay tribute to the dedicated doctors, nurses and staff at three hospitals the Rechts der Isar in Munich, the London Clinic, and Park Hospital Davyhulme. Without them, all would have been lost.

I doubt whether anybody could have been more squeamish than I was about having an operation. I hope those who feel the same way will gain in confidence from this story of how the medical teams managed to get us survivors back on our feet. We should marvel, and be forever grateful for those people who dedicate their lives to working with the sick and the maimed and the injured. Theirs is a calling which has uplifted mankind throughout the ages, with the flame of human kindness, in carrying out duties which cause the lesser among us to turn away from the often gruesome sights they see, and the deeds they are asked to perform in hospitals and casualty stations.

Those of us who were saved can never repay the debts we owe to so many people. This book is just one small way of saying thank you, to my wife, brothers, sisters and close family, but also to the doctors and nurses who not only helped me to get well again, but also to laugh again, just as we did in that Elizabethan airliner carrying the Manchester United party as she rode high in the skies over Central Europe on the afternoon of February 6th, 1958.

COME SIT WITH ME

About 90 minutes after leaving Belgrade airport I was beginning to feel a trifle restless. It was not that I was nervous about the flight, but I was beginning to feel bored. There I was sitting alone, towards the front of the aeroplane, in a seat facing the rear. All my newspaper friends were sitting at the back, and I was feeling a little annoyed with myself for refusing to sit beside Frank Swift in the tail of the plane and insisting on moving to the front, simply because I could see there was more room up there in a group of seats facing the rear.

In Belgrade it had been a crisp cold morning: blue sky, a slight hint of sunshine and white snow on the ground. Not a lot. Just enough to make it look a Christmassy scene.

As we boarded our Elizabethan airliner, Frank Swift was already fastening his safety belt. When he saw me he waved and pointed to the empty place next to him.

Cmon, Dad, he shouted, Ive kept this seat especially for you. Right back here in the tail which is the safest place.

Swifty always said that, because in World War II so many tail gunners had been thrown clear and survived when their bombers crash-landed.

I shook my head: No thanks, Frank. Theres a lot of space in those rearward facing seats up front, I said.

Be like that, Dad, said Frank, laughing out loud. Whats the matter, are you too good for the rest of us?

I never did find out why Swifty always referred to me as Dad, although he was several years older than me. In fact, while I was still at school he had been one of my sporting heroes. I got to know him really well when he retired as Englands and Manchester Citys goalkeeper to write about soccer for the News of the World. I enjoyed his company, and the previous evening we had had a few convivial drinks together, so I was really looking forward to having a few more laughs with him on the flight home.

To this day, I dont know what caused me to refuse his kind offer to join him at the back of the aeroplane, except that I had once read that, in a terrible air crash, the only person to survive had been in a seat facing the rear of the plane.

Next page