Table of Contents

Guide

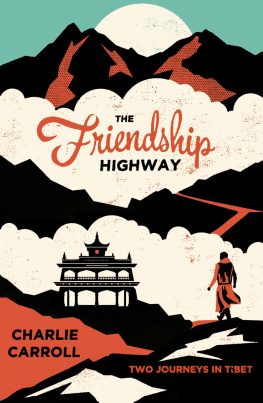

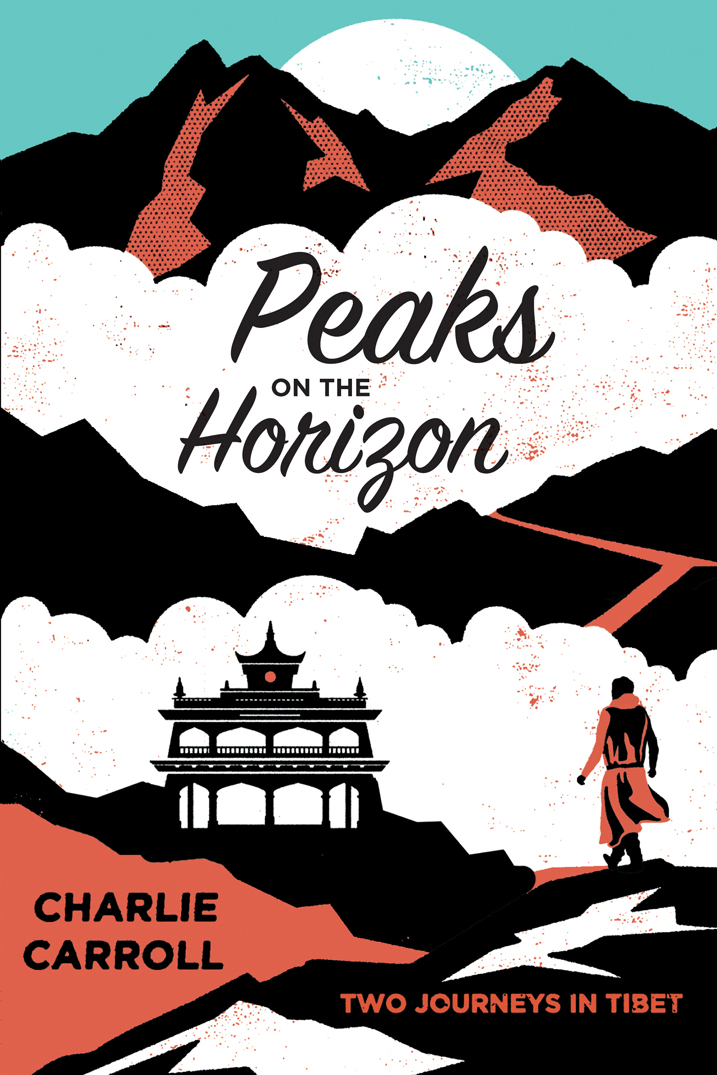

Copyright 2015 Charlie Carroll

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Is Available

Soft Skull Press

An Imprint of COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.softskull.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

e-book ISBN 978-1-61902-517-2

For my father

Barrie

Note from the Author

To protect the identities of all the Tibetans and Chinese who candidly spoke to me during my journey, and to prevent any possible incarceration which could result from their admissions to a writer, all names in this book have been changed.

At the time of my journey, 1 was worth approximately 10 yuan.

The Tibetan chapter titles are simply the phonetic spelling of the numbers one to fifteen ascending in the Tibetan language.

Contents

Lobsang felt his mothers fingers curl around his skinny bicep as she gently shook his arm. He kept his eyes closed. It was customary for her to wake him for school in this way each morning, and customary for him to pretend he was still asleep. The rules of the game stated that his mother would shake him four times, repeat his name twice and then walk away from his bed to shout: Father! Our Lobsang has died in the night. We had better get a new Lobsang. This was the childs cue to fling back his yak-hair blanket, leap to his feet and announce: I fooled you! Then his mother would kiss him, the game would be over, and the new day would begin.

Once, he jumped from his bed and said: I fooled you! But get the new Lobsang so he can go to school for me. His mother did not kiss him that morning, and he understood that he had broken the games rules. From then on, he stuck to them religiously.

This time, it was his mother who was breaking the rules. She had shaken his arm a full eight times and repeated his name at least five. Then she said something unexpected: Lobsang, you must open your eyes, Lobsang.

This he did, if only to reprimand her over her disrespect for their morning ritual, but the words stuck in his throat when he felt the cold outside his blanket. It was still early March, he knew that, but this was not a morning temperature. This cold meant something was wrong. Instead of reproaching his mother, he asked a simple: Why?

Later, his mother said, stroking his forehead. Now, you must do what I say. No complaints.

OK! he grinned, suddenly excited because he knew what his mother was up to. He leapt from the bed and performed a little dance on the floor to make his mother smile. She did not.

Not so loud! she whispered.

With pantomime-steps, he tiptoed across the room. Not so loud! he whispered back, giggling at his impression and at his mother for trying to surprise him in this way. It was all too obvious. He grabbed at her hand and pulled her ear down towards his mouth. Are we going on a pilgrimage? he breathed.

Lobsangs mother smiled at her youngest son. Yes, she said. Were going on the best kind of pilgrimage. Were going to see Dorje.

Dorje! For all Lobsangs guesswork, he had never supposed a visit to his eldest brother would be the surprise. He adored Dorje and had thrown tantrum after tantrum when his brother had left over a year ago. When the outbursts had not worked, Lobsang came to understand that he could only bring Dorje back by being good. And this he had been really good for a whole year. Now he was going to get his reward.

His mother led him out of their small house. A gigantic truck sat on the street with its lights off but its engine running. Following his mothers gestures, Lobsang climbed into the back of the truck and picked his way through the crates, boxes and bags to find in a corner his sister, Jamyang, and his brother, Chogyal. Jamyang held out her arms and Lobsang tripped into them.

Were going on a pilgrimage to see Dorje! he said.

I know, Jamyang replied, but she did not smile.

Chogyal said nothing and did not look at Lobsang as their mother and father climbed into the truck and sat with them. Their father took a thin but large cotton sheet from one of the crates and pulled it over them all. Lobsang felt disappointed that his father was coming on the pilgrimage (he had often wished that Dorje was his real father), but he at least seemed to know how to get the truck to start and stop. One bang of his fist on the wall behind them was enough to get the truck rolling; another brought it to a quick halt.

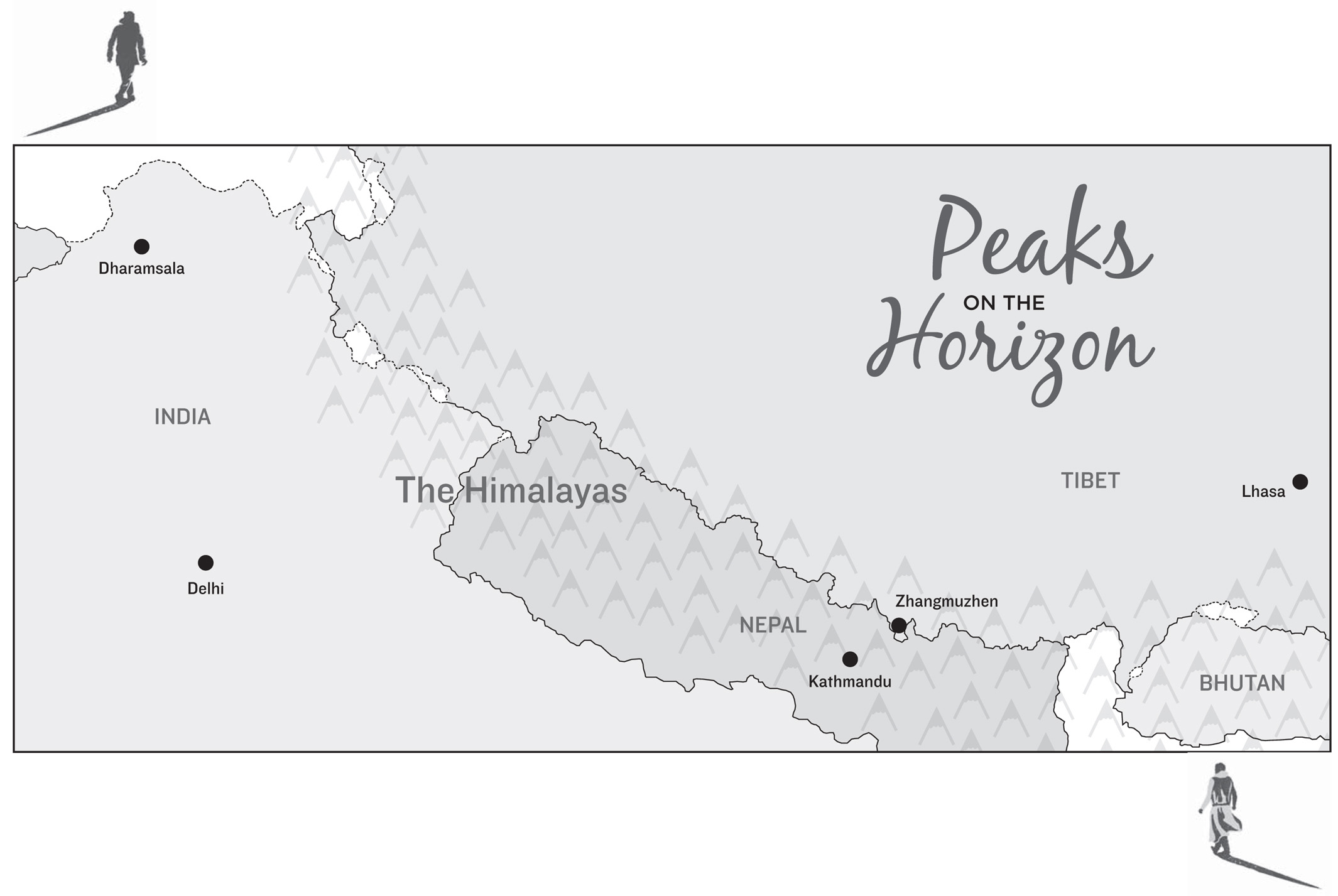

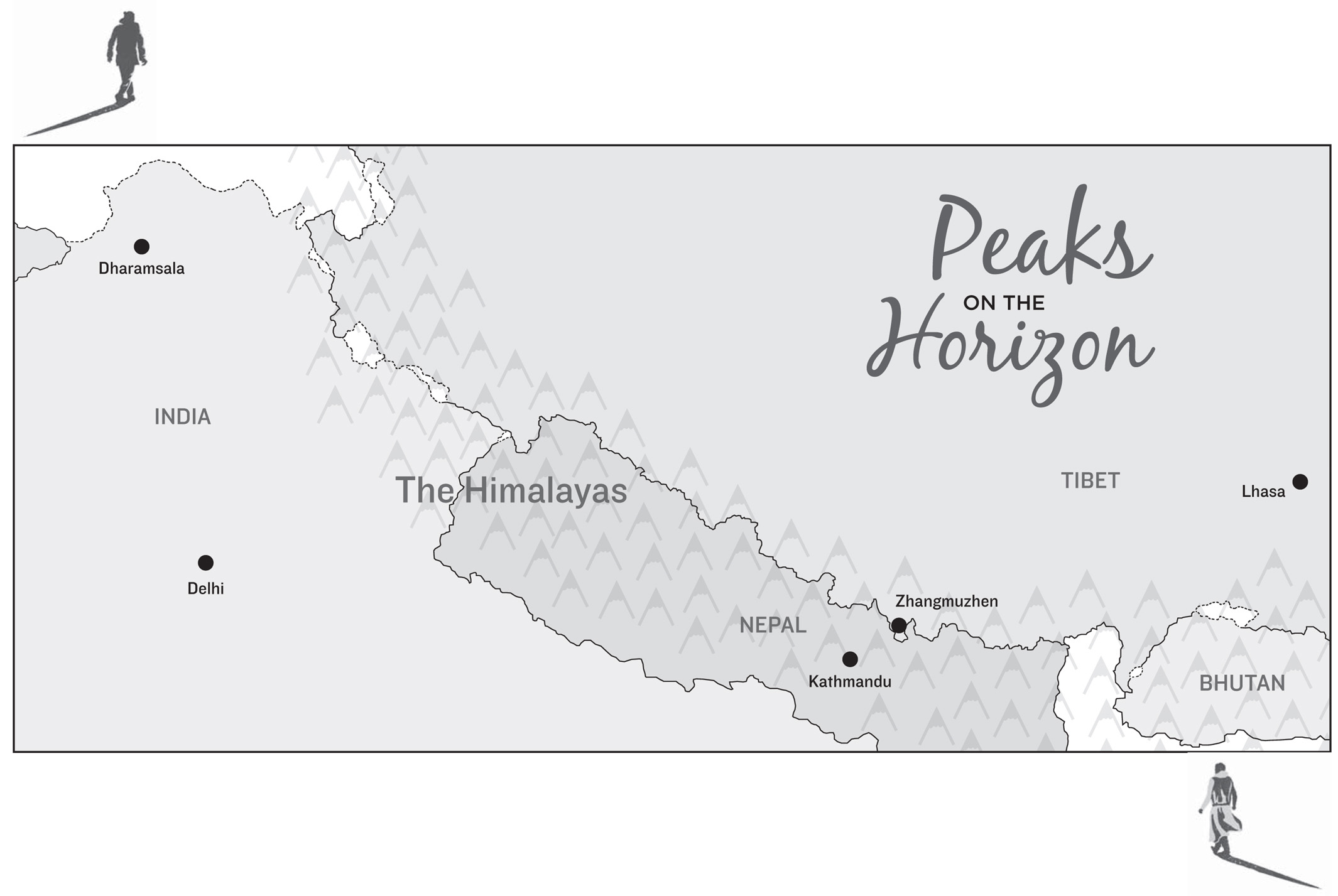

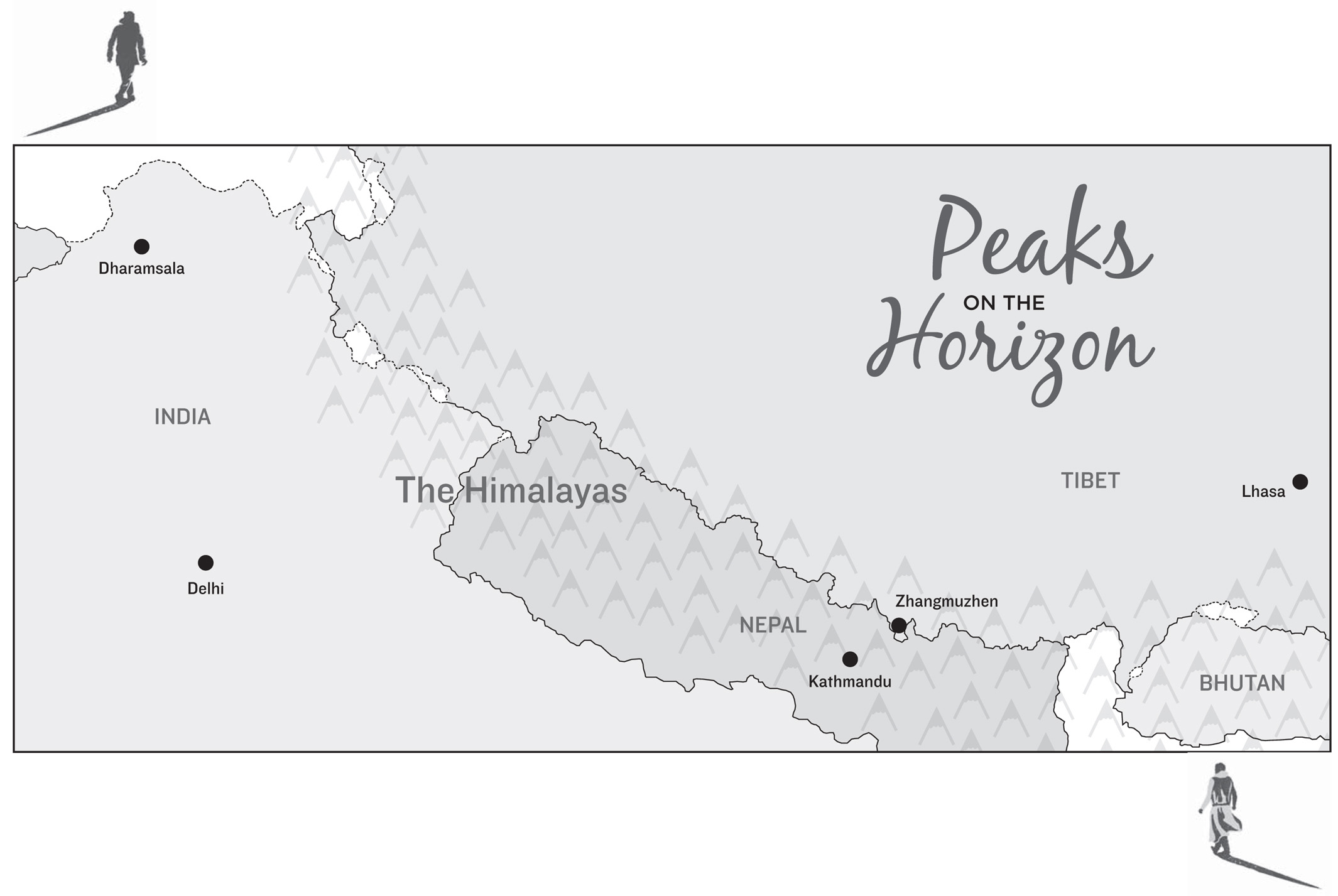

Remember, his mother told him as they bumped slowly out and along the streets of Lhasa. You must do what I say.

Lobsang pressed his hands together in a gesture of prayer, bowed his head, and grinned. What must I do, mother? he called above the roar of the engine.

She smiled back at him, reached out one hand and stroked his forehead. For now? Sleep.

He felt aggrieved. Sleep? He had just woken up!

The more you sleep, his mother remonstrated, the quicker time will pass, and youll get to see Dorje sooner than if you stay awake the whole time.

Such logic had an immediate effect, and Lobsang closed his eyes without another word.

Though the truck bounced and its interior fluctuated between searing heat and numbing cold, Lobsang slept, and, when he didnt, he pretended he did. Sometimes, his mother or Jamyang nudged him and told him to eat. He would groan and mutter I am asleep, though he made sure to chew on the tsampa or the cubes of cheese gently nudged between his lips. He opened his eyes to greedily accept any offer of sweet, milky tea, but made sure they remained shut and his mouth remained mute whenever yak-butter tea took its place. He had never liked yak-butter tea, and never would, even though years later he would drink at least five cups a day and proclaim its benefits to anyone listening.