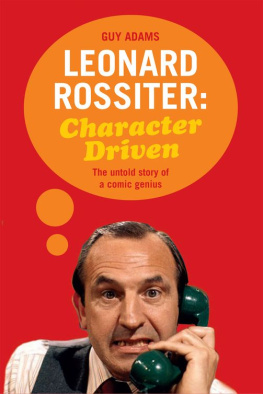

I would like to thank all the people who took the time to discuss their memories of Leonard Rossiter. Particularly: David Nobbs for his kindness and wit, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson for their coffee and voluminous sofa, Don Warrington for his stunning voice and profundity with regards to the business and Joe McGrath for his jolly frankness. This would be a much thinner book without all their contributions.

Special thanks are due to Camilla Rossiter. She had a difficult task in balancing her fathers wish for privacy and yet also wanting to see a book in print that celebrated his life. I can only hope that I have trodden a respectful line and that she is pleased with the result. I respectfully dedicate this book to her daughter Zoe.

I would also like to express my appreciation to those who went before me, in particular Robert Tanitch and Richard Webber, whose interviews with those who knew and worked with Leonard Rossiter were invaluable in building a full picture of his life. A list of the books and other sources I have used is given on pages 2913.

Thanks to Stuart and the rest of the team at Aurum for their hard work and support and to the marvellous Jane Donovan for dotting my Is, crossing my ts and generally making it look like I can string a sentence together.

Finally, thanks to Leonard Rossiter for being good enough to merit the intrusion. He was one of our very best and if this book whets the readers appetite for a repeat viewing of his many performances then I consider it a success.

When approaching the life of an actor one is faced with multiplicity from the off: most of us are able to separate ourselves into the working us and the one at rest. For an actor that distinction is never so simple. After all, actors are masked at the best of times its what theyve trained for. They have the interchangeable faces of the characters they create, the face they use to talk to their audience or press, the one they share with their family and friends

In some cases they even forget which face serves which purpose, becoming lost beneath a stack of peeled personalities. Peter Sellers was once asked to record a religious reading for an album of such things. After agreeing to this, he soon came unstuck. He tried it first in the crusty voice of an archdeacon but that wouldnt do Then a soft Welsh lilt perhaps thoughts of Neddie Seagoon, the Goon Show character, came to mind then a thick Yiddish accent No, no, the recording engineer didnt like that. Couldnt he just record the piece in his own voice? Sellers crumbled at the thought, utterly lost. Theres no such thing, he replied.

Then again some actors, and Leonard Rossiter was one of them, have no such mental frailty: they see acting as a job, as solid and practical as bookkeeping or car mechanics. They can analyse the business of performance unlike the frequently confused folk to whom it comes only too naturally. These performers are often unsung, the sheer technical proficiency of how they approach their work overshadowed by bigger, more eccentric personalities.

When speaking to actor, James Grout in one of the many interviews conducted for this book, he started the conversation by stating: There are some actors who gather amusing anecdotes at every step of their career, one can think of many Ive worked with over the years then there are those who simply dont. Len was one of the latter. (And no, this wasnt the most disheartening thing I heard during an interview: that would have been the actor whose name I shant mention for the sake of sparing blushes who, on being asked when they had first met Leonard, replied: Oh nineteen erm nineteen Oh dear, nineteen something! I couldnt be more specific, really.)

So no amusing anecdotes here then? Well no, quite a few actually. But its true Leonard was a simple, workmanlike man which I mean in a complimentary sense and his home life really no different to anyone elses. When recalling her father, Camilla Rossiter brings to mind the hardworking man, buried in scripts and learning lines, or the caring father, who took her to the park or local swimming pool. It is not a childhood of glitzy celebrity parties and shocking revelations.

Actress Margaret Courtenay who worked alongside Rossiter as part of the Bristol Old Vic company in the 1960s once observed: Len did not seem like an actor at all. Off-stage, he might have been an accountant or bank clerk.

So, what makes Leonard Rossiter a man, when not working, so utterly normal that he might have been mistaken for a bank clerk worthy of a book? Quite simply: his work. Not many actors create such an utterly iconic character that they will forever be remembered, performances repeated and discussed ad nauseam on the 100 Best shows that certain channels like to fill their schedules with. Leonard did it twice, concurrently, in Rupert Rigsby and Reginald Perrin. Even that frankly astounding achievement underplays the true weight of his career indeed, it was merely five years worth of performances while his career stretched for thirty.

A lot of people think of him purely as a comic actor, says Camilla, they will always say, Oh, I remember your dad, he was so funny I suppose its because of those two series that people particularly remember but of course he did lots of work that wasnt comic, lots of different roles. I think, like with anyone in that profession, he would have wanted to be remembered as an actor across the board, someone who could play the whole range. But thats the way it goes, I suppose. Lets be honest, an actor is glad to be remembered for anything!

As director, and close friend of Leonards, Joe McGrath says: At the end of the day, its the work thats important, nothing else matters at all. Certainly, Rossiter always thought so he had no interest in sharing the details of his home life, nor by all accounts were they, for the most part, unusual enough to be worth sharing; he had the roles that he played, from fascist dictators to seedy landlords, neurotic businessmen to escaped convicts That is where the story of Leonard Rossiter lies: in his journey to achieve the best work of which he, or for that matter anyone else, was capable.

This book looks at his life through the context of those roles, how he developed the characters and how they, in turn, may have developed him.

Things that make me laugh are black jokes, which some people find distasteful. I like the story about Arthur Lucan who was, of course, Old Mother Riley. Hed been doing pantomime for about ten weeks, with the audience full of kids screaming his name. He goes off to his dressing room. Then theres a call for him, and he doesnt answer. The theatre manager has to go onstage and break the news. And he says, Please could I have your attention? Kiddies, shush, please! I have some very sad news: Old Mother Riley is dead. And someone from the back shouts, Oh no, she isnt!

Leonard Rossiter, Live from Two, 1980

Its the spring of 1984 and Leonard Rossiter has just finished filming both a new ITV sitcom, Trippers Day, and the lead role in The Lifeand Death of King John, part of the BBCs ambitious plan to adapt the entire works of Shakespeare for the small screen. The former will receive distinctly mixed reviews, the latter fares better.

But that lies in the future. For now, Leonard is back where he is most comfortable: the theatre. While there can be no doubt that it is television that has made him a household name, theatre is where his heart lies. Theatre offers actors the opportunity to refine a performance over an extended period and to feed off the audience as they ply their trade. It is an immediate medium, uncluttered by the complications of camera angles, lighting rigs and a performance broken up into bite-size pieces for shooting. The drama is cleanly and consecutively told no altering the script to make an easy shooting order here, a process rather like asking a pianist to start in the middle and then bash out all the loud notes first, filling in the rest later. In theatre, actors tell their story: its as simple, and potentially transcendental, as that.