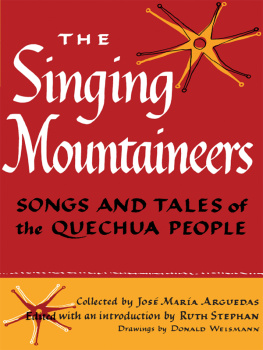

COLLECTED BY

JOS MARA ARGUEDAS

EDITED AND WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

RUTH STEPHAN

DRAWINGS BY DONALD WEISMANN

THE SINGING MOUNTAINEERS

Songs and Tales of the Quechua People

The Quechua Songs were collected by JOS MARA ARGUEDAS, taken down while they were sung in Quechua, then later translated into Spanish by him.

The Threshing Songs of Angasmayo were collected in the same way by MARA LOURDES VALLADRES, and translated by her from Huanca, a dialect of Quechua, into Spanish.

The Quechua tales were collected by FATHER JORGE A. LIRA, and were translated into Spanish by JOS MARA ARGUEDAS.

The tales were translated from the Spanish into English by KATE AND ANGEL FLORES.

The songs and the essays were translated from the Spanish into English by RUTH STEPHAN.

AUSTIN UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

Copyright 1957 by Ruth Stephan

Copyright renewed 1985

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

Library of Congress Catalog Number 57-008825

Library ebook ISBN: 978-0-292-76225-1

Individual ebook ISBN: 978-0-292-79220-3

DOI: 10.7560/701267

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Editor is grateful to the Peruvian poets Emilio Westphalen and Manuel Moreno Jimeno and to the Peruvian artist Judith Westphalen for checking the consistency of the English translations of the songs with their Peruvian nature.

Appreciation is due, too, for assistance and for the use of books in the following libraries: Yale University Library, The Hispanic Foundation and the Music Reading Room in the Library of Congress, the Library of the Pan American Union in Washington, D.C., the Latin-American Collection of the University of Texas, the American History Room in the New York Public Library, Columbia University Library, and the Greenwich Public Library in Greenwich, Connecticut.

CONTENTS

TO READ these songs and tales only as living folklore would be to lose a good part of the excitement of their presentation, charming as they are within themselves, for in their background, like brilliant steady stars, or, perhaps, like the mountains the Quechua people live upon, are the centuries of civilizations from which they have emerged, civilizations which were among the highest Indian cultures on the American continents. One of the greatest of these was the Inca, and, although the Incas are renowned for the highly organized administration of their vast mountainous empire, for the engineering of their roads and architecture, for their genius in agriculture, for the opulence of their art in ceramics and weaving, an art that contemporary artists still copy, they are distinguished, too, in our wonder at their history because they had no written language. To us, the heirs of a civilization with a passion for naming, for listing, and for preserving facts and fancies in writing, the circumstance that the Incas did not develop a written language is astonishing, nor would it be so astonishing if they had not excelled intellectually in other ways. When we remember their schools and widespread teaching with no textbooks other than the quipus whose knotted strings recorded numbers, we must respect the exact memories demanded and the flexible libraries their minds had to become.

Andean Indian legend has an answer for this. The seventeenth century Spanish historian Fernando Montesinos recounts as history the story of how the knowledge of letters was lost in Peru and why it never was recovered. He had it, he claimed, from the amantas, or learned men, whom he met during his travels in Peru, but it is more probable he read it in the library of the college at La Paz in the manuscript of Bias Valera, the sixteenth century Jesuit priest whose words, said Garcilaso de la Vega, were pearls and precious stones. Since Bias Valera was half Peruvian and spoke Quechua as his native tongue, he would have been able to collect a great deal of valuable information on the living habits, legends, poetry, all that had preceded, and it is a misfortune that his writings disappeared long ago, making it impossible for modern historians to read and evaluate his records.

According to Montesinos, in pre-Inc times, over a thousand years ago by our calculations, confusion was caused in Cuzco by the entrance of strange peoples in Peru, and when the King, Tito Yupanqui, was killed in battle by the ferocious enemies, the government of the Peruvian monarchy was lost and destroyed. It did not come into its own for four hundred years, and the knowledge of letters was lost. There must have been a resurgence of some kind of letters, however, for several pages and several kings later, Montesinos tells about the troubled King, Tupac Couri Pachacuti, who came to believe that communication in writing was the source of the pestilences, superstitions, and vices spreading among his people. The use of quilcos, parchments or leaves of trees with writing on them, was banned effectively by a death penalty, and the law became so ingrained in the nature of the land that many years afterwards when an amauta again invented written characters he was burned alive.

This, of course, is legend, even, some say, a fancy by Montesinos, not proved history, and it is assumed that neither the Incas nor the tribes preceding them ever conceived of the art of writing. The people of the Peruvian Andes have lived by oral traditions from earliest known times to the present day, through the long glory of the Inca reign, and the four hundred years since the Spanish conquered the country and began to impress their customs, their religion, and their language upon it. They have persisted in their traditions, moreover, in spite of the attempts of the Spaniards to substitute their own, and in spite of the changing culture of the coastal cities and plains just over the seaward ridges of their mountains, even after Peru became an independent nation. This deep adherence to their own ways is appreciated by anyone who becomes intimate with the conventions of the Andean Indians, seeing how many of them maintain ancient practices of magic in the seclusion of their houses and in mountain retreats, how they have kept their own religions within the cloak of Spanish Catholicism, joyously celebrating the Catholic ceremonies which fall so conveniently close to the agricultural rituals of the Inca calendar, letting their early religious festivals exist in modem Indian games.

Further, the Quechua language, which derives from the court language of the Incas, is spoken more extensively now than at the end of the Inca reign in the sixteenth century. The Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, one of the fortunate products of the Spanish conquest, his father a Spanish captain and his mother an Inca princess bequeathing to him the passions and intelligences of each side, urged the Spaniards, in his interesting history,

![Robert Choi - Korean Folk Songs: Stars in the Sky and Dreams in Our Hearts [14 Sing Along Songs with the Downloadable Audio included]](/uploads/posts/book/423508/thumbs/robert-choi-korean-folk-songs-stars-in-the-sky.jpg)