I have great gratitude to the estate of James M. Cain via Folio Management to quote from Cains works and letters.

C AIN, YOURE TWENTY-TWO YEARS OLD, YOUVE JUST QUIT YOUR FIFTH job, your wish to become a great opera singer will never come true. So how do you intend to spend the rest of your life? he said to himself, sitting on a Lafayette Park bench in the fall of 1914, the White House at his back.

Youre going to be a writer, said a voice out of the blue.

Was he about to take another preposterous plunge, as he had when he set out to become an opera singer? Or were there discernible forces that brought him to this seemingly gratuitous decision? Taking stock was a habit. Though he looked Jewish, only Irish blood ran in his veins, so he might assume a likely propensity for talking well and telling stories effectively. But only his reports for the Maryland Road Commission suggested he could write effectively.

As president of Washington College, his father had proven how charmingly he could talk. His mother, trained to sing opera, had inspired his own ambition. She had also taught him how to speak and write with clarity, correct grammar, and brevity. Of his three sisters, only Virginia showed any literary talent. His brother Edward was the familys bright star, athletic, handsome, and charming, like his father, good at everything his father understood and admired, and a proficient musician, like his mother.

Neither his father nor his mother seemed to think Jamie would amount to much.

But from early years to this moment of decision, he had developed a prospective writers background in reading. Literature was his favorite

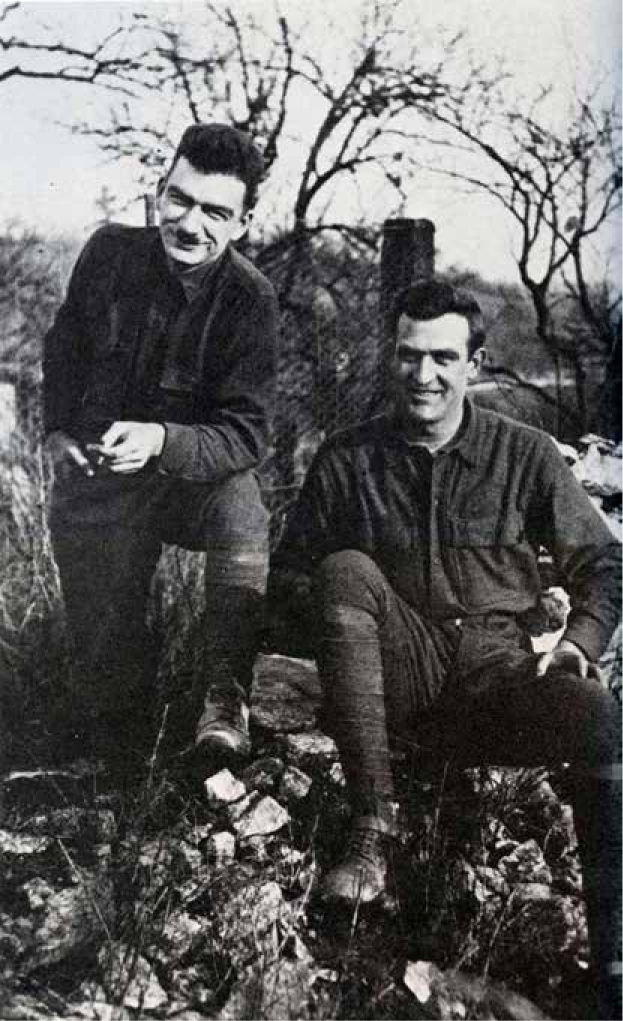

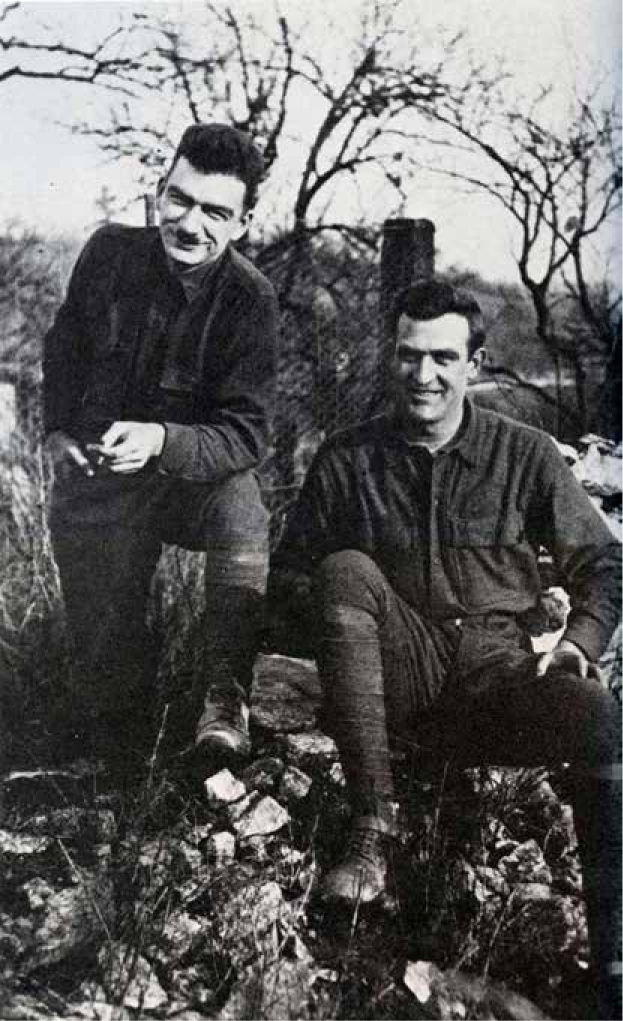

James M. Cain and Gilbert Malcolm in uniform. PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

subject. His favorite work of fiction was Alice in Wonderland. Other favorite books were The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, The Last of the Mohi-cans, The Virginian, Vanity Fair, Treasure Island, The Three Musketeers (hed taught himself French so he could read Dumas The Black Tulip in the original)and Whos Who in America.

During the uneventful first twelve years of his life in Annapolis and the next six across Chesapeake Bay in Chestertown, he had produced no dramatic evidence of an inclination toward writing. Rebellion, especially against religion, might be considered a telling factor in the background of a writer. At thirteen, when he realized he was faking it, he had broken with the Catholic Church, which was a hick operation in Chestertown. Writers usually had memories of interesting characters and buddies from their childhoods. He had Ike Newton, town storyteller, and boyhood friend Bushrod Howard, rebel against authority. As superintendent of Annapolis schools, his father had unwisely honored his request that he skip from third to fifth grade, making him ever-after a midget among giants in school.

As a precocious fifteen-year-old student at Washington College, he had taken no part in athletic or other extracurricular activities, belonged to no organizations, held no jobs, and declined to edit the campus magazine. His father had looked with wholehearted disapproval upon his complete indifference to campus affairs. When he graduated in 1910 at eighteen without distinction, he knew he had already failed to live up to his fathers expectations.

After graduation, the realization hit him that, contrary to the atmosphere of the grand style in which he had been raised, life was hard, that work was every mans daily lot. Growing up, hed had no idea at all that a man was supposed to do something with his life. Having assessed the visible choices, he didnt want to do anything, though he had a vague intention of becoming somebody and showing up in Whos Who.

His high-toned college girlfriend, Mary Clough, who was teaching school, treated him now with a lofty disdain.

It pained him now to look back over four years on a series of jobs whose only object was to make a living. The mumps had released him from a six-month stretch with Consolidated Gas and Light of Baltimore, secured through his fathers connections, performing hateful routine tasks with ledgers. Inspecting roads and writing reports for the Maryland Road Commission had been enjoyable, but getting laid off was humiliating. As principal of the high school in the little village of Vienna, Maryland, on the Eastern Shore, hed learned a few things about teaching.

When he suddenly decided to quit to take singing lessons, his mother was shocked. You have no voice, no looks, no stage personality. You have some musical sense, but its not enough. What he did have was the first big decision hed made on his own, and hed gone ahead with it. To make a living while taking lessons from a teacher who seemed to share his mothers assessment, he tried to sell insurance. He failed. Facing the fact that his singing talent was minimal, that his enthusiasm for practicing was faint, he quituated.

Kanns department store hired him to sell Victor records and Victrolas. Meeting some of the fine singers who came to Washington was exciting, but he had to have a raise. Kanns disagreed.

He had discovered that he had a certain incompetence in several fields of work. The only one who lacked the Cain-Mallahan good looks, physically weak and uncoordinated, he was unsuccessful in love and lust. But the lunge at music had been at least an action in the right direction, for his mind was mainly aesthetic. And singing, which his gifted mother had given up for marriage, had been a rebellion against his father, who saw a law career for him. He had failed to win his fathers approval and so to remove the barrier between them. He had even failed to impress his mother, to whom he had always felt very close. Sitting on the bench, he had the feeling hed just awarded himself a consolation prize for his failure to become an opera singer. But the years of indecisiveness, of searching, were past, now that God had made up his mind for him.

Some things were over now. He had, in a way, come through.

Expecting to astonish his parents with his firm resolve, they astonished him by seeing it as the wish most likely to come true for James Mallahan Cain, their firstborn.

He went down to Richmond to seek the advice of his favorite living writer, Henry Sydnor Harrison, author of the bestseller Queed, but he was not at home.

Living with his parents in Chestertown, he secretly wrote short stories, mainly out of a desire to project local color and background. Passages memorized from Harrisons highly successful novels provided stylistic models: his tongue un-locked and he began to speak his heart. It was not speech as he had always known speech. In all his wonderful array of terminology there were no words fitted to this undreamed need. He had to discover the words somehow, by main strength make them up for himself. They came out stammering, hard-wrung, bearing new upon their rough faces the mint-mark of his own heart. Perhaps she did not prize them any the less on that account. As his stories came back from the magazines, he suspected that they lacked narrative thrust. At least, he was learning to type, practicing on the machine in his fathers office at the college. The look of x-outs made him feel uneasy, so the method he developed was to type neat copies of all drafts after the first. But even as he set about working out his self-assigned destiny, his father drew him into another in that series of interim jobs.

When his father asked him to fill in for a teacher who was ill, he accepted the offer. The classes were in English and mathematics in the preparatory school across the road from the college. Although he had taught a year in high school, he now became even more convinced that teaching was mainly a matter of preparation, of knowing what you intend to try to teach today. The only way he could face those boys was to become an expert on grammar, syntax, rhetoric, and especially punctuation. He performed so well that when the instructor took a job elsewhere, his father asked him to manage the entire preparatory department. That meant that he had to live in the dormitory and discipline the boys.