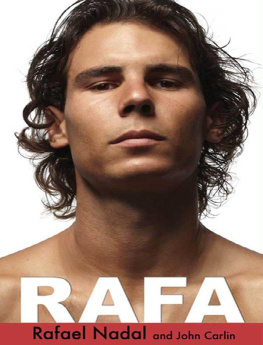

Copyright 2022 by Rafael Agustin

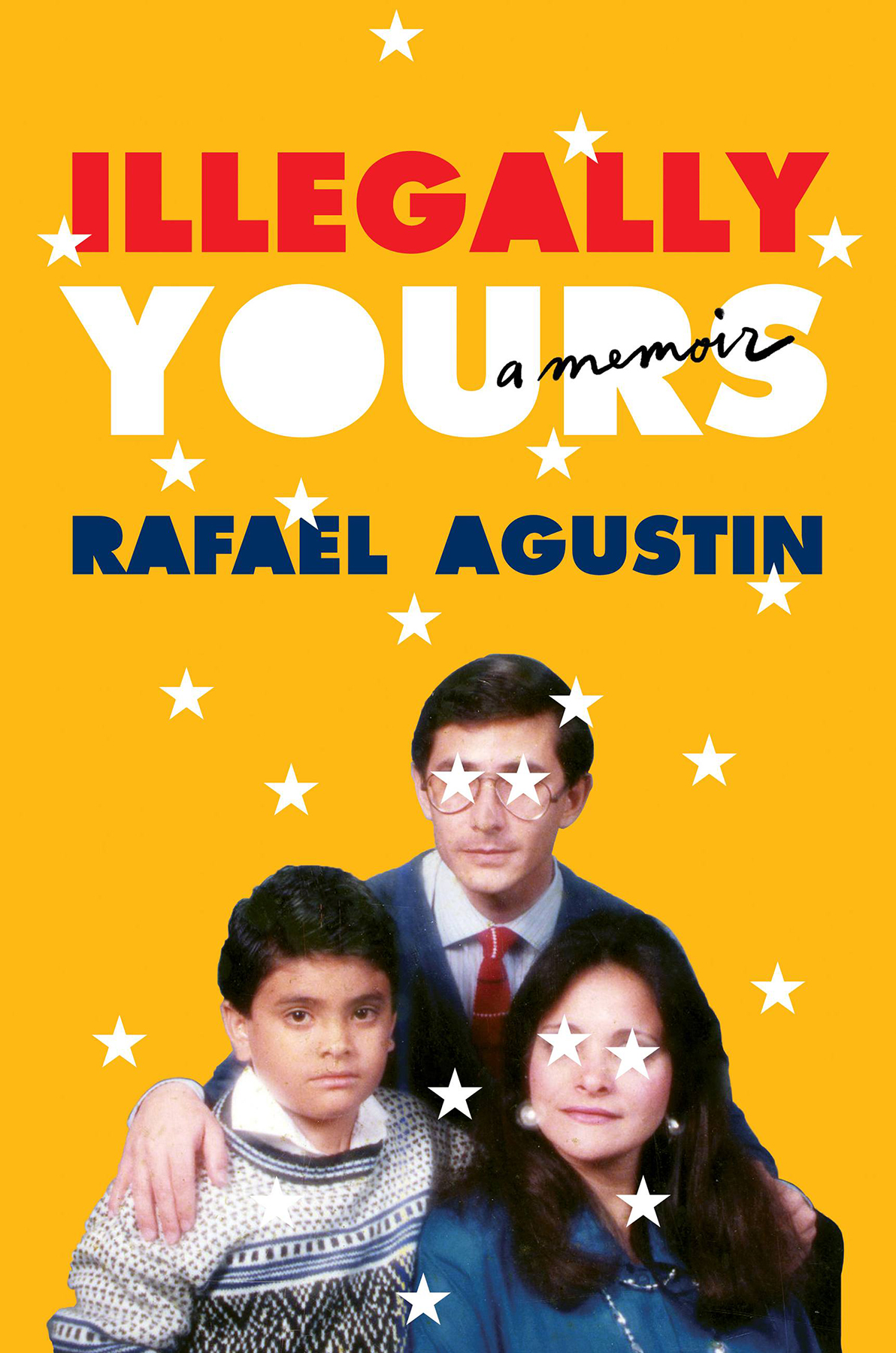

Cover design by Henry Sene Yee

Cover photograph courtesy of the author

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas,

New York, NY 10104

grandcentralpublishing.com

twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First edition: July 2022

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Agustin, Rafael, author.

Title: Illegally yours : a memoir / Rafael Agustin.

Description: First edition. | New York : Grand Central Publishing, 2022.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022004300 | ISBN 9781538705940 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781538705964 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Agustin, Rafael. | Ecuadorian AmericansBiography. | NoncitizensUnited StatesBiography. | Illegal immigrationUnited States.

Classification: LCC E184.E28 A48 2022 | DDC 973/.0468866dc23/eng/20220307

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022004300

ISBNs: 9781538705940 (hardcover), 9781538705964 (ebook)

E3-20220511-JV-NF-ORI

To my two Violetas

T he metal bars slammed frighteningly close to my face. I stared at the immigration official on the other side of the cell, wide-eyed. I could not believe what was happening. The nightmare Id feared as a child was now becoming a reality. I was being deported. Granted, it was not at all how Id worried it would come to pass. There were no kids. There were no cages. I was being detained in a Spanish jail inside an airport. I didnt even know they had jails inside airports!

I had just flown cross-country from Los Angeles to New York, and then caught a late-night international flight across the Atlantic to Spain. When I exited the plane and walked up to the customs kiosk, the Spanish officer asked for my immigration papers. He was shocked to see my Ecuadorian passport.

What is this? he exclaimed.

I said that was my Ecuadorian passport, but not to worry. I was a resident of the United States of America now, and quickly flashed my brand-new, shiny green card. Frustrated, the Spanish officer said, That doesnt matter. Ecuadorians, Colombians, and Cubans are not allowed in Spain without a special visa. Waitwhat?

Since when? I demanded to know.

Since last month, said the stone-faced customs official.

I didnt know it at the time, but Spain had just passed a draconian law trying to cut off immigration from certain South American countries, as well as other economically struggling nations, such as Morocco and Poland. Spain opened their borders when they needed cheap labor, and then closed them just as quickly when the work dried up. It dawned on me then that all immigration policy around the world was used the same way by every country: to control labor. But I was not there to work or give a lecture about immigration policy. This was my first trip to Europe and I wanted to wild out like any young, beautiful, reckless American.

I was rushed over to an immigration officer standing nearby, who then marched me over to a hidden office at the airport. The Spanish were so secretive. A new disheveled immigration official arrived, but he refused to speak to me until a lawyer was present to inform me of my rights. A clumsy Spanish lawyer, juggling his coffee and briefcase in the same hand, showed up half an hour later. At least the Spanish legal system was serious about everyone having legal counsel. The lawyer briefly said hi before launching straight into a rapid-fire, legal language exchange in Spanishlisp and all! I tried to follow along, but it was very difficult to make out. This was not the type of Spanish Id grown up accustomed to in Southern California. Nodding his head, my lawyer agreed with something the official said, and then the two Madrileos turned to me.

Why didnt you get a special visa to come? asked my newly appointed attorney.

Quick on my feet, I replied, Why the hell did the airline let me fly without me having one?

The two men launched into another comedic-sounding, rapid-fire legal language exchange in Spanish and then nodded to each other once more. The immigration official picked up the phone, let out one final machine-gun-sounding Spanish exchange over the landline, and then slammed his phone shut.

Continental Airlines has just been fined five thousand dollars for letting you fly, the official said matter-of-factly.

What? No! Thats not what I wanted to do, I said, suddenly more concerned about the airlines well-being than my own. My lawyer chimed in and tried to explain once more that I was not allowed to be in Spain without a special visa. Annoyed, I snapped and said, Fine, just send me back home. By home, I clarified, I meant the United Statesjust in case they wanted to send me back on a cheaper flight to South America.

As brave as I sounded on the outside, I was actually starting to panic on the inside. This was my greatest fear personified. In all my years in the United States as an undocumented immigrant, I dreaded one thing and one thing only: deportation. The official stated, We have no choice but to send you back to the United States. Fine, I barked back. I didnt care anymore. The excitement to explore the Spanish countryside rocking my George Clooney Caesar haircut completely left my body. This experience could not get any worse. Unfortunately, added the official, the next flight doesnt depart until twenty-four hours from now. It was presently 10:30 a.m. in Madrid.

Okay, I said, finally giving up. Are you putting me up in a hotel?

The immigration official gave me a worried look and then stated, Well its not quite a hotel.

Moments later, I glared at the immigration official from the other side of the cell I was locked inside of. To be honest, I was madder at myself. I had hidden my immigration status from American authorities for so long, yet let my guard down on my first trip to Europe. Not that long ago, this would have been a real problem

T he first time I heard the word America was as a small child when my mom, grandma, and I took my moms youngest brother, my uncle Andres, to the Jos Joaqun de Olmedo International Airport in Guayaquil, Ecuador. My uncle was going to visit family in the United States. I watched him lovingly hug my mom and grandma good-bye.

May God protect your path every step of the way, said my grandma in Spanish.

My uncle waved at us as he boarded his plane, and we watched the warm headwind help lift that aircraft off into the bright blue tropical sky. I tugged on my moms dress and asked, Wheres Uncle Andres going?