Contents

Guide

Copyright 2022 The Estate of Cookie Mueller

This edition Semiotext(e) 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Semiotext(e)

PO BOX 629, South Pasadena, CA 91031

www.semiotexte.com

Special thanks to Mallory Curley, Robert Dewhurst, Raymond Foye, Nan Goldin, Chlo Griffin, Gracie Hadland, Max Mueller, Bradford Nordeen, and Janique Vigier.

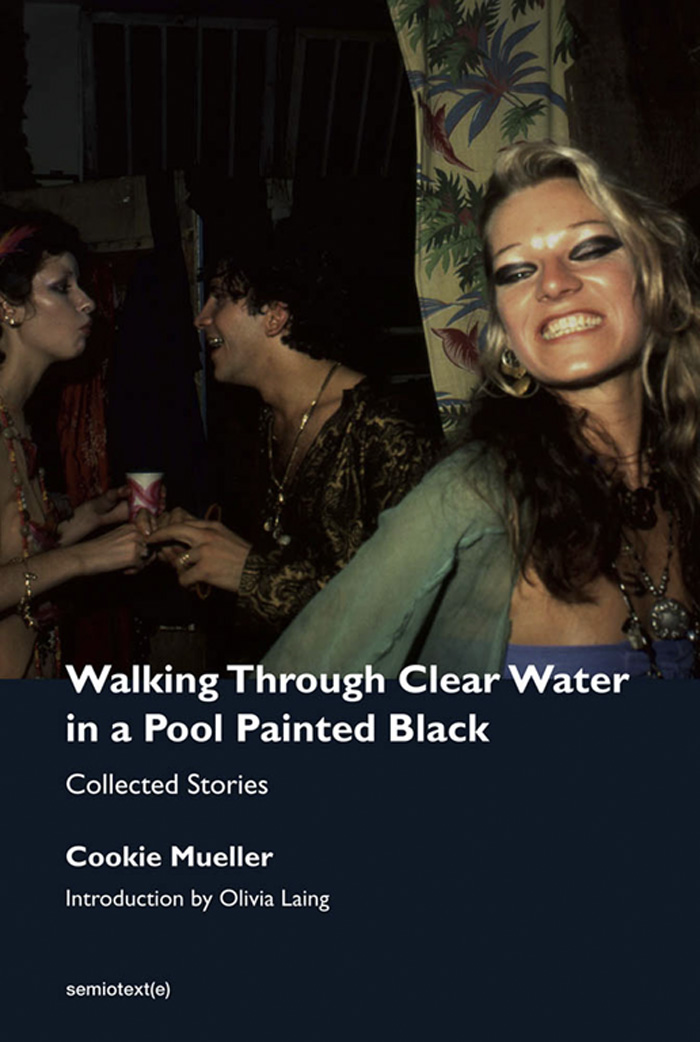

Cover Art: Nan Goldin, Cookie at Sharon's birthday party with Lisette and Genaro, Provincetown, 1976. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.

Design: Hedi El Kholti

ISBN: 978-1-63590-166-5

Distributed by The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London, England

d_r1

Introduction by Olivia Laing

Cookie

In my favorite photograph of Cookie Mueller, by her friend Nan Goldin, she has one hand on her heart, one on a wall, and is laughing so hard she might fall over. Her wrists, fingers, ears are crammed with jewellery, her head's flung back and her enormous bleached lion's mane is damp with sweat. She looks a riot, like the most fun you could possibly have, the walking epitome of downtown style.

She was born in Maryland in 1949 and christened Dorothy. Somehow, she explains in My BioNotes on an American Childhood, I got the name Cookie before I could walk, a nickname from her brother Michael, who died in a climbing accident when he was fourteen. As a teenager she dropped out of high school, hit the road, and did a hairy stint in the acid-fuelled Oz of San Francisco before crash-landing back in Baltimore, where at the age of twenty she met the wizard in the diminutive, moustached form of John Waters. Their first encounter, at the screening of his debut Mondo Trash, so enchanted him that she starred in his next five movies.

Actress and kohl-eyed muse in a monkey fur jacket, sure, but her strongest suit was as a writer. In 1976 she moved to New York, where alongside raising her son Max, dealing coke, and hosting parties, she wrote poetry, had a regular no holds barred advice column for East Village Eye, and did a stint as art critic for Details. In one column she jokingly predicted that in the future art history students would take modules on the painters of the East Village, as indeed they do; another reflects on the recent death of Basquiat, one of the world's citizens who was translating the universe on a canvas. There's also a lot of gossip, grouching about gentrification and off the wall riffing, much of it enviably quotable.

She wrote her first book aged eleven, making a cover out of beer case cardboard and Saran Wrap and filing it on the shelves at her local library. This lost juvenilia (321 pages!) was followed by several collections of her writing, including the epistolary novella Fan Mail, Frank Letters and Crank Calls (1989) and the Waters-era memoir Garden of Ashes (1990).

The first I came across was Walking through Clear Water In a Pool Painted Black, published shortly after Cookie's death of AIDS-related pneumonia on 10 November 1989. I was given it a couple of years later, a precocious fifteenth birthday gift from an older cousin. Sarah had taken it upon herself to oversee my countercultural education, and Cookie was a must. The syllabus also included Stripping by Pagan Kennedy, My Education: A Book of Dreams by William Burroughs, and Safe in Heaven Dead, a Hanuman paperback by Jack Kerouac that fitted pleasingly in the pocket of my then-uniform, a man's suit jacket, on the back of which I'd scrawled in lipstick Get Out of My Church.

All of those books left a mark, but Cookie Mueller was next level: a how-to manual for a life ricocheting joyously off the rails. It provided an introduction to the avant garde delights of John Waters and Fassbinder, but more importantly it was a primer for an outlaw way of life, in which every crisis or devastation was merely an opportunity to demonstrate unflappable worldliness and grace. Cookie careened through terrifying situations abduction, rape, boat wrecks, car wrecks, house fires, a friend ODingwith languid ease, a good witch on bad drugs. Her style was neither macho nor touristy. She was merely reporting, hilariously, on the world as she saw it. As she said to an employer trying to inveigle her into an unwanted threesome: Why does everybody think I'm so wild. I'm not wild. I happen to stumble onto wildness. It gets in my path.

This collection, first pieced together by Amy Scholder in 1997 as Ask Dr Mueller and now reissued in chronological order, represents the whole kit and caboodle of the Mueller oeuvre, complete with tales of piss queens and chicken-fucking, as well as advice on syphilis, loneliness, lactose intolerance and what to cut cocaine with (inositol). A monumental amount of drugs are consumed. In one single day, the young Cookie meets the Manson Family girls (like ducks quacking over corn), attends an LSD capping party, rides with the Grateful Dead to San Quentin prison for a concert, has a brief rest with some heroin, goes to a peyote ceremony, meets a Satanist who summons a footman of Beelzebub on top of Mount Tamalpais, escapes over a dissolving Golden Gate bridge, takes a bath, goes to a Jim Morrison concert, gets raped by a stranger, escapes again, and ends the night talking about aesthetics, Eastern philosophy, Mu, Atlantis, and the coming of the apocalypse, this time on cocaine mixed with crystal meth. Other days were less eventful, but not by much.

Experience is a badge of pride. It matters to stay afloat, live on your nerves, keep smiling. The signature Cookie phrases are too bad and oh well, the textual equivalent of a shrug. It's not that she thinks nothing matters or anything goes (rapists, she comments at one point, ought to have red hot pokers rammed up their wee wees); more that it's a point of dignity to poke fun at the terrors, to be able to metabolise whatever life throws at you, just as she casts aspersion on a boyfriend for sweating out his drugs.

I wonder at that tone now. Before rereading, I might have called it hardboiled or affectless, but that's not quite right. There is a great art to handling losses with nonchalance, she observes. Some things, especially pain, don't need to be spelled out, but rather defanged, the raconteur's survival strategy, alchemised into material for a comic story, a transaction she once described as sublime. What comes off these pages now is in no way anaesthetised or anhedonic, but rather a deep relish for adventure, a powerful, vibrating pleasure at the oddness of people, and the capacity of language to freeze even the most plainly terrifying or distressing material, to make it something that can be appreciated and shared, a communal pleasure rather than a private humiliation. It goes without saying that this is not the dominant style right now, which for this reader at least makes it all the more desirable.

It strikes me too that Cookie's world of happenstance and chance encounter has been obliterated by the internet, gone without trace. She never seems to pack a suitcase, let alone book a ticket or plan an itinerary. Her life is wide open, revelling in unscripted, unscreened contact and surprise. It's high risk, high reward. Getting a ride with a stranger might result in a gunpoint abduction, but her idiosyncratic approach to travel also generates new friendships, lovers, parties to attend, places to stay. I used to know a lot of people like that, in my own dropout days, but I can't think of anyone now who doesn't use Google as a prophylactic against the unexpected, a charm against getting lost that comes at a higher price than might have been predicted.