A s the convoy of limousines drove toward Viennas Schnbrunn Palace on June 4, 1961, thousands of Austrian citizens thronged the streets. They cheered till they were hoarse, jubilant that their country had been chosen to play a part in what many were predicting to be the end of the cold war. It was the most exciting thing to happen to their country since the Anschluss.

But it wasnt their peripheral role in hosting the potentially history-changing Vienna Summit between the United States and the Soviet Union that had attracted most of the screaming onlookers that afternoon. It was a chance to glimpse the exciting new American president, John F. Kennedy, and his glamorous wife, Jackie.

Like most of the rest of the world, Austrians were captivated by the charisma and youthful hopefulness of the handsome president, who promised a new era in international relations.

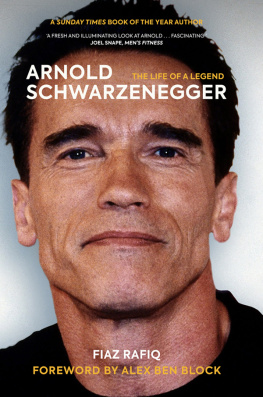

As the thirteen-year-old Arnold Schwarzenegger listened with his family to news of the meetings 125 miles away and the adulation being poured on Kennedy, he was swept up by the excitement. Even his normally reserved mother, Aurelia, could barely contain her enthusiasm for the youthful president.

For days leading up to the summit, the Austrian media had gushed with stories about Kennedy and his exciting background, portraying him as the American equivalent of royalty and describing his aristocratic upbringing, his world travels, his beautiful and accomplished wife, his rapid ascension to power.

To many a young boy in a similar situation, raised in a small provincial town, under the thumb of an overbearing father, with no apparent way out, Kennedys life might seem like a fairy tale.

But as a young Arnold Schwarzenegger took in the scene that day, he vowed to himself that one day his countrymen would cheer for him the way they did for Kennedy.

A LMOST HALF A CENTURY AFTER John F. Kennedy s starring role at the Vienna Summit, I landed in the Austrian capital searching for clues to help explain how Schwarzenegger achieved a dream that at the time seemed impossible.

My guidebook was his 1977 autobiography Arnold: Education of a Bodybuilder. This was written long before most of the world had ever heard of him; still, reading the bookwhich is closer to a weight-training manual than a memoirmakes it obvious that he was confident even then.

It is a two-hour drive to Thal, the pastoral village where Schwarzenegger was born in July 1947 to Gustav and Aurelia Schwarzenegger.

Thal, it turns out, is a suburb of Graz, the capital of the Styrian region. In advance of my trip, I had been told by an Austrian friend that Styrians are considered the hicks of Austria, though this may reflect the snobbishness of the cosmopolitan Viennese more than a fair assessment of Styrias people. Still, the region is often mocked for its lack of sophistication, its conservative moral values, and its lack of worldliness. And while I had always assumed that Schwarzeneggers much-parodied thick accent is simply a product of his foreign upbringing, it seems that it is in fact a characteristic of the Styrian way of talkinga dialect commonly known as High German.

In this tiny village of about 2,000 inhabitantsunlike Vienna, where many people spoke Englishit was very difficult to find anybody who could speak more than a few English words. And when people did speak English, their thick accent made it difficult to understand what they were saying. My first destination was Schwarzeneggers birthplace at Thal Linak 145. After asking directions of three people who spoke only German, I finally said to a woman on a bike, Schwarzenegger house. She smiled and pointed the way.

When I reached the large two-story house, there was nobody at home. A sign indicated that the Anderwalt family lived here now, and I remembered that Frau Anderwalt had given a newspaper interview a few years earlier, explaining that she and her husband had bought the house in 1979. She mentioned that whenever Schwarzenegger visited the village, he always brought a camera crew to accompany him to his boyhood home. Whenever the cameras were rolling, she recalled, he was very jovial. But as soon as they were switched off, he was cold and unfriendly.

His attitude may stem from the fact that he did not have very fond memories of growing up here. Although Thal now brags about the origins of its most famous resident, whose formative years were spent in the postcard-pretty village, Arnold Schwarzeneggers childhood was anything but idyllic.

THERE IS AN OLD SAYING about Schwarzeneggers homeland: The Austrians are brilliant. They have managed to persuade the world that Beethoven was Austrian and Hitler was German. The fact is that Hitler was born in Austria and his countrymen welcomed him with open arms upon his ascension to power. It is the countrys dirty little secret, one that the Austrians are often reluctant to discuss. In the months immediately following World War II, when Gustav Schwarzenegger settled in Thal, nobody in Austria asked what anybody else had done in the war, because nobody really wanted to know the answer.

And so when Gustav moved to Thal in 1946 and applied for the position of police chief, the job was his, despite an official prohibition against hiring former Nazis for police work. Then again, despite the title, the job wasnt very desirable. It paid a mere pittance and most often consisted of directing hikers from nearby Graz who ventured to the village for a picnic or rowboat ride on its picturesque lake.

Gustav grew up in a working-class family in the nearby Styrian industrial city of Neuberg. His father, Karl, was a mountain of a man whose genes are often credited with influencing Arnolds own muscular build. Like Karl, who died in his forties because of a work-related accident, Gustav worked in the Neuberg steel factory before joining the Austrian army for his compulsory military service. He was a talented musician who could play six different instruments, specializing in the flgelhorn. Following his discharge from the army, he worked for many years as a postal inspector and then as a policeman. His life was rather routine, but Karl always dreamed of something bigger, for himself and for Austria.

The answer lay in the nation over the hills.

In 1933, after Hitler took power in neighboring Germany, membership in the Nazi Party was made illegal by the Austrian government, nervous that Hitlers brand of National Socialism would catch on. With a common language and culture, many Austrians considered themselves German and, as the Depression ravaged the Austrian economy, resulting in high unemployment and widespread poverty, many looked longingly at Germanys economic gains and at the fierce national pride that the Fhrer, an Austrian, had instilled.

By 1938, Hitler had made it clear that he considered Austria part of the German Reich and it was only a matter of time before Germany annexed Austria, by force if necessary. As early as 1934, the German leader had signaled his designs when Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss of Austria was assassinated by Nazis in a failed coup.

The Austrian National Socialist Party was still in principle an underground movement, though it had been operating out in the open for months, by the time Gustav Schwarzenegger visited one of its offices in early 1938 and filled out a membership form.