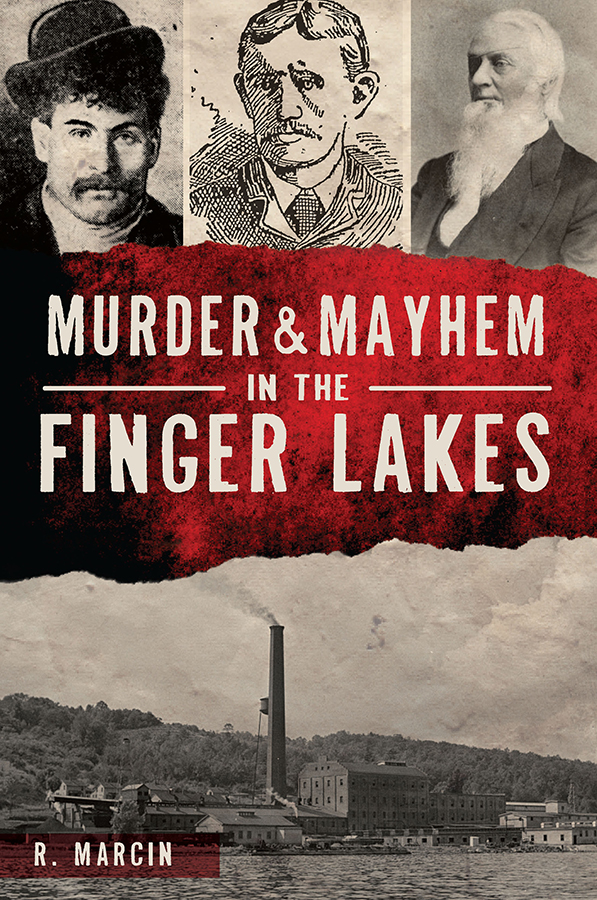

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Rikki Marcin

All rights reserved

First published 2020

E-book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.43967.124.5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020938617

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.614.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

A NOTE ON THE SOURCES

Their absence of psychosocial insight notwithstanding, newspapers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are unsurpassed in their vivid depictions of the era and the lives of its inhabitants. They nonetheless demonstrate an understanding of human nature sufficient to cover murder trials voluminously, delivering cinematically detailed scenes to those denied the privilege of witnessing the proceedings. In unrestrained prose, they offer fragmented portraits of individuals plagued by alcoholism, domestic violence, poverty and illnesses both physical and mental. Editorials, functioning as a Greek chorus, illuminate the degree of sympathy these transgressors aroused and the zeitgeist surrounding them.

Whether the perpetrators disappeared from history or had paragraphs devoted to their final moments, their stories captivated the public. They provided a diversion so desperately needed that people would walk all night to view or be near the site of their executions; they also stirred elemental fears of a disrupted social order. Motives are eternally familiarjealousy, covetousness, an injured egoor obscure even to themselves. Regardless of how far they may be from us, historically or psychologically, the perpetrators and their victims remain embodiments of the unexpected turns any life can take.

Chapter 1

GEORGE CHAPMAN

Waterloo, Seneca County

1828

At a time specified only as after the Sullivan-Clinton campaign of 1779, a road was planked from Geneva to the outlet of Seneca Lake. Concurrent with this occasion, an Englishman, James Uncle Jimmy Nares, erected a brick-and-concrete tavern on the south side of the road above the lake, over the Seneca County border. From his fondness of field sports and foxhunting originated the name Sportsmans Hall for the new public house, and its doors were open to all lovers of fun and frolic.

On Sunday, July 20, 1828, all future associations of fun with Naress establishment came to an end, courtesy of an encounter between his fellow countryman George Chapman, a tailor, and Daniel Wright, a mixed-race hostler at the hall. The origin of their conflict is obscure, but the earliest report, in the Geneva Gazette of July 23, claimed that they had a quarrel and happened to meet about the middle of the day at Naress. They talked it over and were reconciled, but according to a vulgar custom, they had to satisfy their treaty of amity over a bottle of whiskey.

Sixty years after the incident, the Geneva Advertiser gave the most specific account. The men at work on the canal, occupying the temporary shanties in the neighborhood of Sportsmans Hall, made nightly raids on the Nareses currant bushes, especially on Sunday. Mrs. Nares, fearing she would be stripped of her entire crop, requested Wright to endeavor to prevent the pilfering. Wright allegedly found Chapman in the garden picking and eating currants, and the first ill-feeling arose from his remonstrance with the plunderer. This was soon smoothed over, before they drank heavily together and became intoxicated. In the words of the Geneva Gazette, here the smothered flame of resentment again burst forth.

While in the garden attached to the premises, the pair engaged in a scuffle, and Wright apparently threw Chapman. After this, they separated for a while, and Chapman vowed he would kill the d----d negro, using very threatening and violent language. Wright went into the granary and lay on an oat bin, either to escape danger or to go to sleep. Some time afterward, Chapman sought him, shook him awake and said, I am going to kill you. Wright, still befogged by alcohol, replied, If you must kill me, kill me. With both hands, Chapman seized a nearby spade and struck Wright four or five blows on the side of the head.

Chapman went into the hall, announced what he had done and was taken into custody. Wright was carried inside and died about an hour afterward. Chapman exulted in what he had done, according to the New York Americanhe had killed the d----d negro and was glad of it. The Geneva Gazette, however, reported after the frenzy of the liquor subsided, the mind of the wretched murderer awakened to a sense of the horrid deed he had perpetrated and to the inevitable doom which awaits him. After his apprehension, Chapman said he had been a soldierhad helped kill a good many menand now must be hung for killing a d----d negro.

Although Chapman and Wright had originally been labeled excessively intemperate drinkers, Chapman was later characterized as ordinarily a quiet and good citizen, and historians unanimously agreed he was a decent fellow when sober. He had been a soldier in the British army, deserted from Canada and came to New York, where he resided on the north side of William Street in Geneva, some years before he came to public attention. Before the murder, he was employed by William Rodney, who had been the military tailor at West Point. The New York American pronounced Chapmans habits very irregular. As for Wright, the sole description of his character defined him as a very decent man despite his addiction to liquor.

Chapman, reportedly chained to a staple in the floor of the jail in the Waterloo Courthouse, was arraigned at a circuit court of Oyer and Terminer in Waterloo on Thursday, April 16, 1829. Although the fact of murder was admitted, Chapmans counsel attempted to set up a plea of insanity, on which point many witnesses were examined, and every effort made to sustain the defence which talent and ingenuity could suggest.

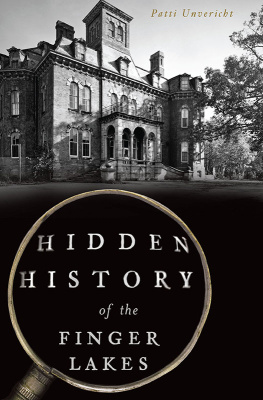

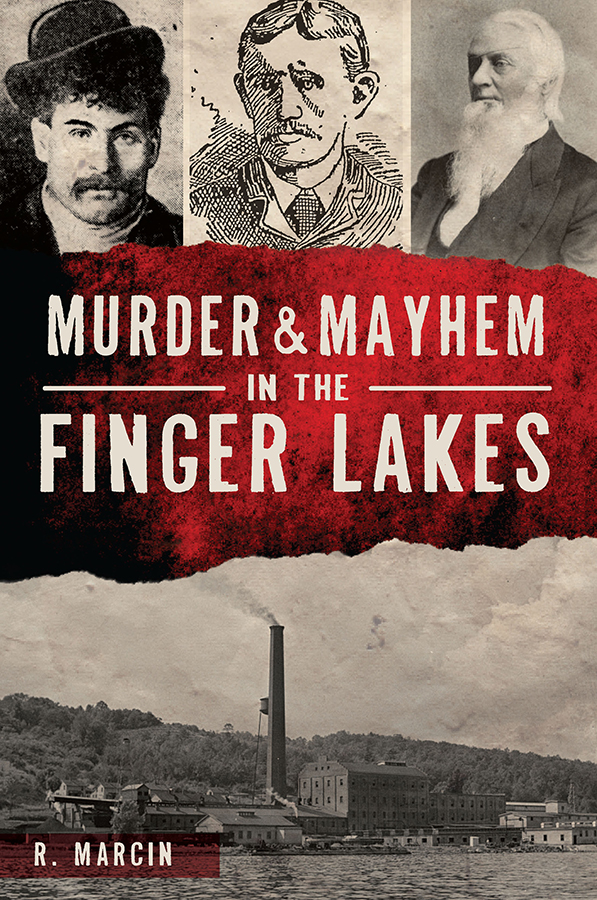

Postcard depicting the courthouse and county buildings at Waterloo, with the jail on the far right. Courtesy Seneca County historian.

In an outr journalistic twist, the newspapers offered no pontifications on the justice of the sentence but rather spied an opening to preach the virtues of temperance and piety. The Waterloo Observer, in torrid, creatively spelled prose, pointed to Chapman as a personification of the misfortunes spawned by dipsomania:

The trial presented a case of the most cold blooded murder, and yet so artless, that charity and vengeance almost combated for the influence of the mind. The only defence set up by the prisoners counsel was that of insanityand to this point of the case the attention of every man, who abberates from that state of sobriety, and that uninflamed exercise of reason with which the God of nature has blessed him, should seriously be called. George Chapman was a few years since a

Next page