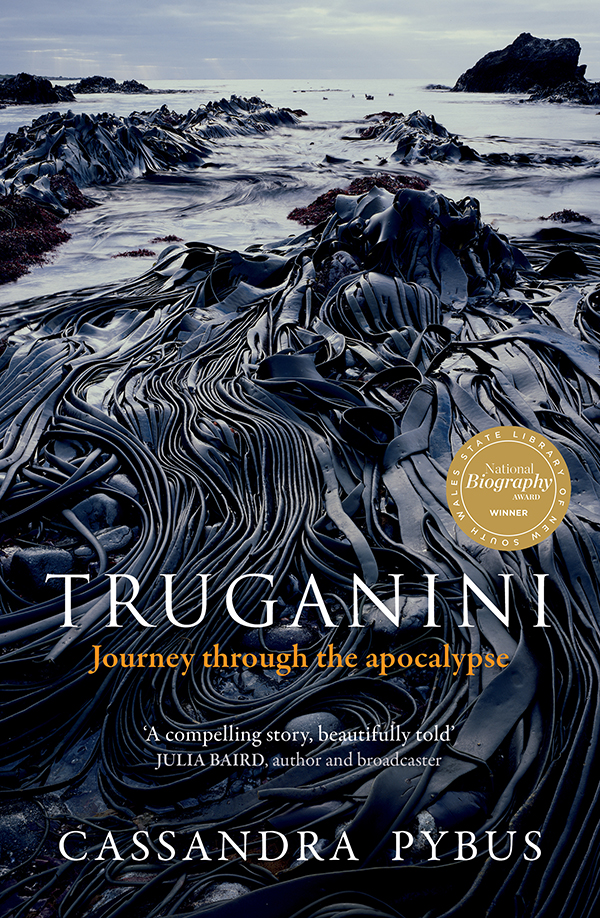

TRUGANINI

CASSANDRA PYBUS is an award-winning author and a distinguished historian. She is the author of twelve books and has held research professorships at the University of Sydney, Georgetown University in Washington DC, the University of Texas and Kings College London. She is descended from the colonist who received the largest free land grant on Truganinis traditional country of Bruny Island.

Other books by the author

Enterprising Women

Epic Journeys of Freedom

Black Founders

The Woman Who Walked to Russia

American Citizens, British Slaves

Raven Road

The Devil and James McAuley

Till Apples Grow on an Orange Tree

White Rajah: A dynastic intrigue

Gross Moral Turpitude

Community of Thieves

First published in 2020

Copyright Cassandra Pybus 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

This manuscript won the University of Melbournes 2018 Peter Blazey Fellowship and the research was assisted by the Neilma Sidney Literary Travel Fund, The Myer Foundation and Writers Victoria.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76052 922 2

eISBN 978 1 76087 369 1

Internal design by Philip Campbell

Maps by Guy Holt

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Philip Campbell Design

Cover photograph: Peter Dombrovskis, Giant kelp, Hasselborough Bay, Macquarie Island, Tasmania, 1984, National Library of Australia, courtesy of Liz Dombrovskis

For Lyndall Ryan

Country

You see it

You are going to the country

Go away to it.

Song of the captive women in the Bass Strait islands, 1830, transcribed by George Augustus Robinson

CONTENTS

HALF BURIED IN the sand, uprooted stalks of kelp are like splashes of dark blood against the white quartzite, ground fine as talc. Tendrils of kelp flounce lazily in translucent shallows that gradually deepen to turquoise, turning Prussian blue at the horizon. Beyond the sand, matted tentacles of spongy pigface creep over the dunes to disguise rubbish middens of crayfish, oyster, abalone and scallop shells that have been tens of thousands of years in the making.

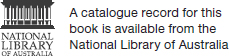

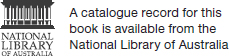

This beach reclines at the far end of an exquisite body of water in the far south-east corner of Tasmania known as Recherche Bay, so named by the French explorer Bruni DEntrecasteaux, who rested his ships Recherche and Esprance in the bay during April and May 1792. Before the French arrived, this place was called Lyleatea. It was an important ritual site for the Nuenonne, who journeyed in bark canoes from the long offshore island to the north they knew as Lunawanna Alonnah to meet with clans who travelled overland from the west coast. For millennia they made this trip: the same seasonal migration, the same ritual feast. It was during one of these seasonal visitssome twenty years after DEntrecasteaux named this placethat Truganini was born, the youngest daughter of Manganerer, senior man of the Nuenonne.

Today, the name of Truganini is vaguely familiar to most Australians for having achieved undesired celebrity as the last of her race, finding fame when she died in 1876. Sadly, a lot of what is said and written about her is myth and fabrication such as can be found on any Google search. Australians should know about how she lived, not simply that she died. Her life was much more than a regrettable tragedy. For nearly seven decades she lived through a psychological and cultural shift more extreme than most human imaginations could conjure; she is a hugely significant figure in Australian history.

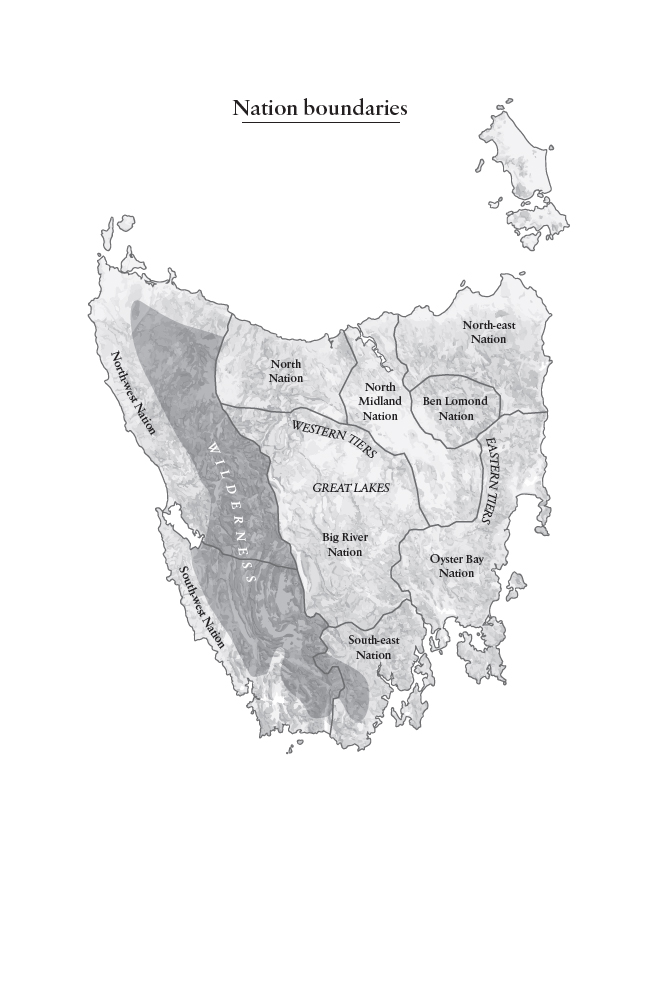

Truganini compels my own attention and emotional engagement because her story is fundamental to my life story. My great-great-grandfather was the biggest beneficiary of the expropriation of Truganinis traditional country of Lunawanna Alonnah, renamed Bruny Island by colonial settlers. I owe Truganini and her kin my charmed existence in the temperate paradise where my family has lived for generations. The life of this woman, Truganini, frames the story of the dispossession and destruction of the original people of Tasmania. Their rapid dispossession, and its terrible aftermath, is the foundation narrative of my family.

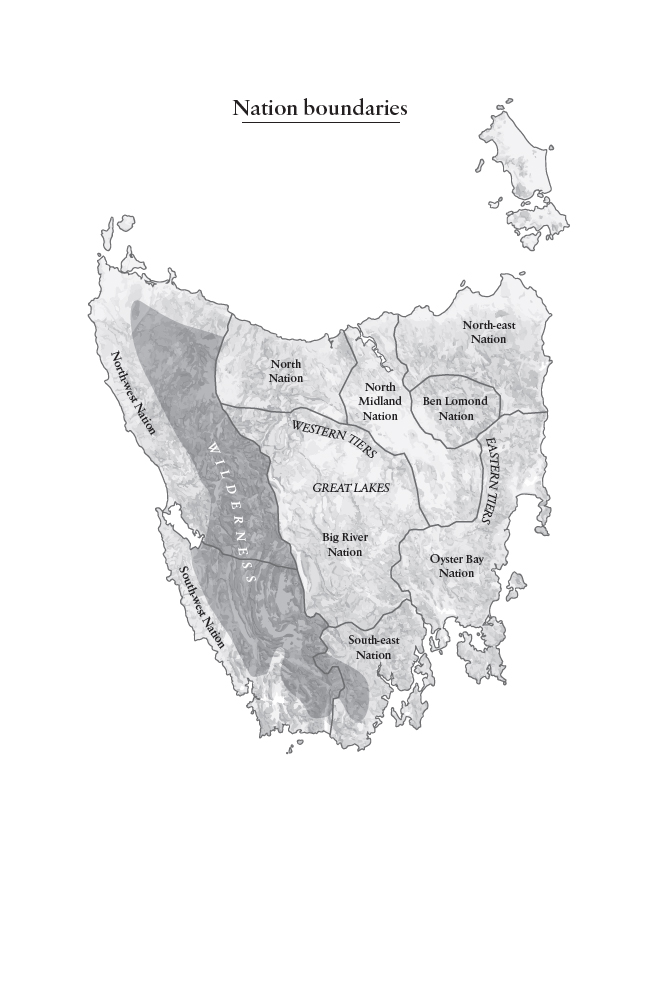

Richard Pybus was fresh off the boat from England in April 1829, with his wife Hannah, son Henry Harrison and daughter Margaret, when he was handed a massive swathe of North Bruny Island, an unencumbered free land grant, even while Truganini and her family were still living there. Some time later he was rewarded with an equally huge land grant in the southern part of the island. For no payment whatsoever, he received well over 2000 hectares of Nuenonne hunting grounds while the original owners of the island, of whom Truganini was the last, were paid with anguish and exile.

Early in the twentieth century my great-grandfather William Pybus and his brothers regaled the British collector Ernest Westlake with stories their parents had told about the young Truganini when she was a regular visitor to the Pybus land, where they would give her gifts of tea and sugar, maybe potatoes or damper. The brothers had their own eyewitness accounts of Truganini as an older woman, living in exile yet still a common sight walking across their land in the 1850s and 1860s. By rights, of course, it was not their land but hers. They would never have seen it that way.

Growing up in Tasmania, I knew nothing of this. Like all Tasmanian schoolchildren, I heard the mawkish tale of the lonely old woman in the black dress and the shell necklace who was the last Tasmanian, but no one ever told me of my family connection to Truganini. I doubt anyone knew. Or cared. I left Tasmania when I was nine and never gave her any thought. A quarter of a century later, my friend Lyndall Ryan, who was in the process of rescuing the original people of Tasmania from historical amnesia, showed me references to my colonial ancestor in the journals of the self-styled missionary George Augustus Robinson, who had a smaller land grant adjacent to Richard Pybuss. The neighbours became friends, sharing evangelical commitment and a love of literature. Pybuss extensive library contained a copy of Thomas Macaulays