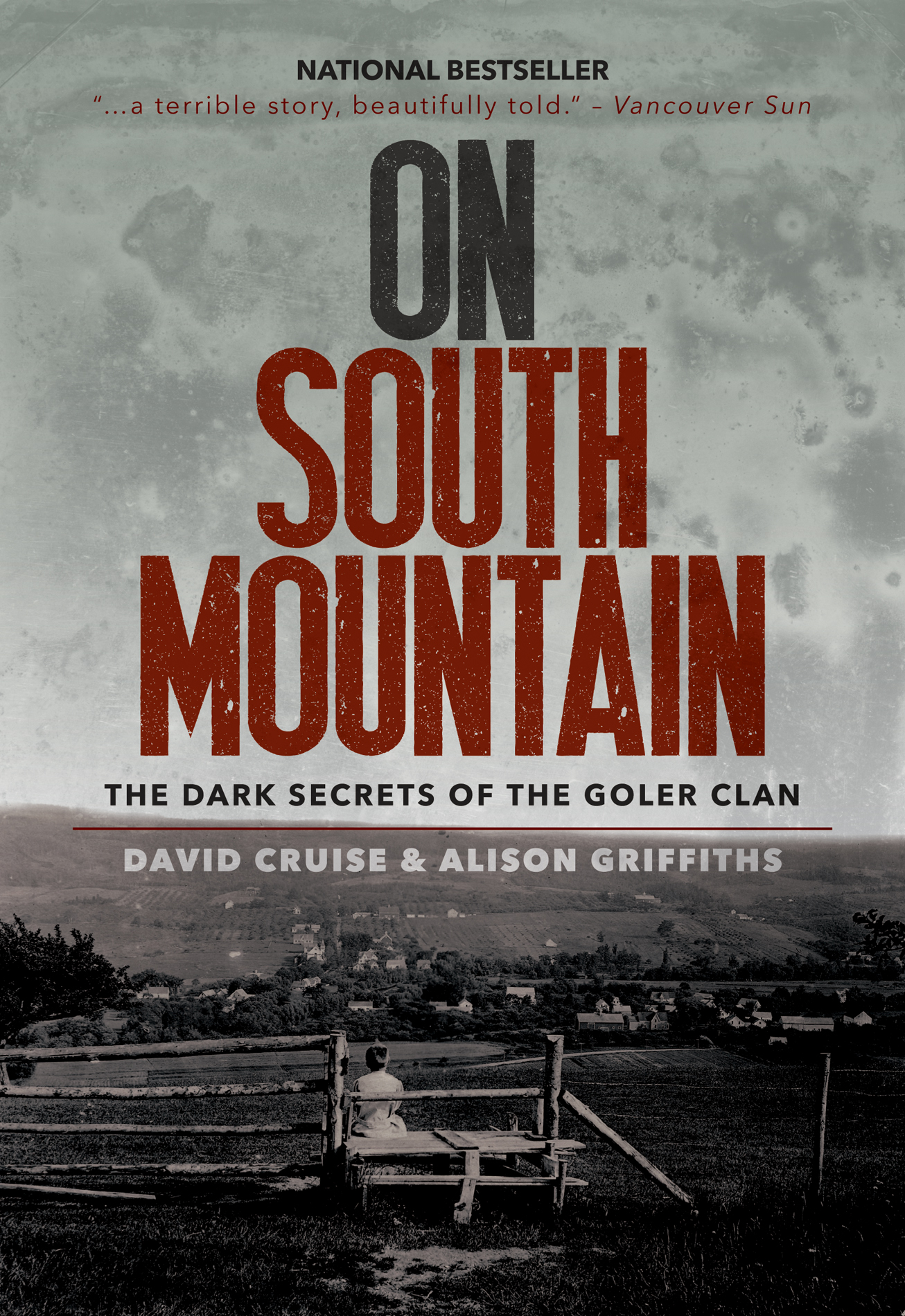

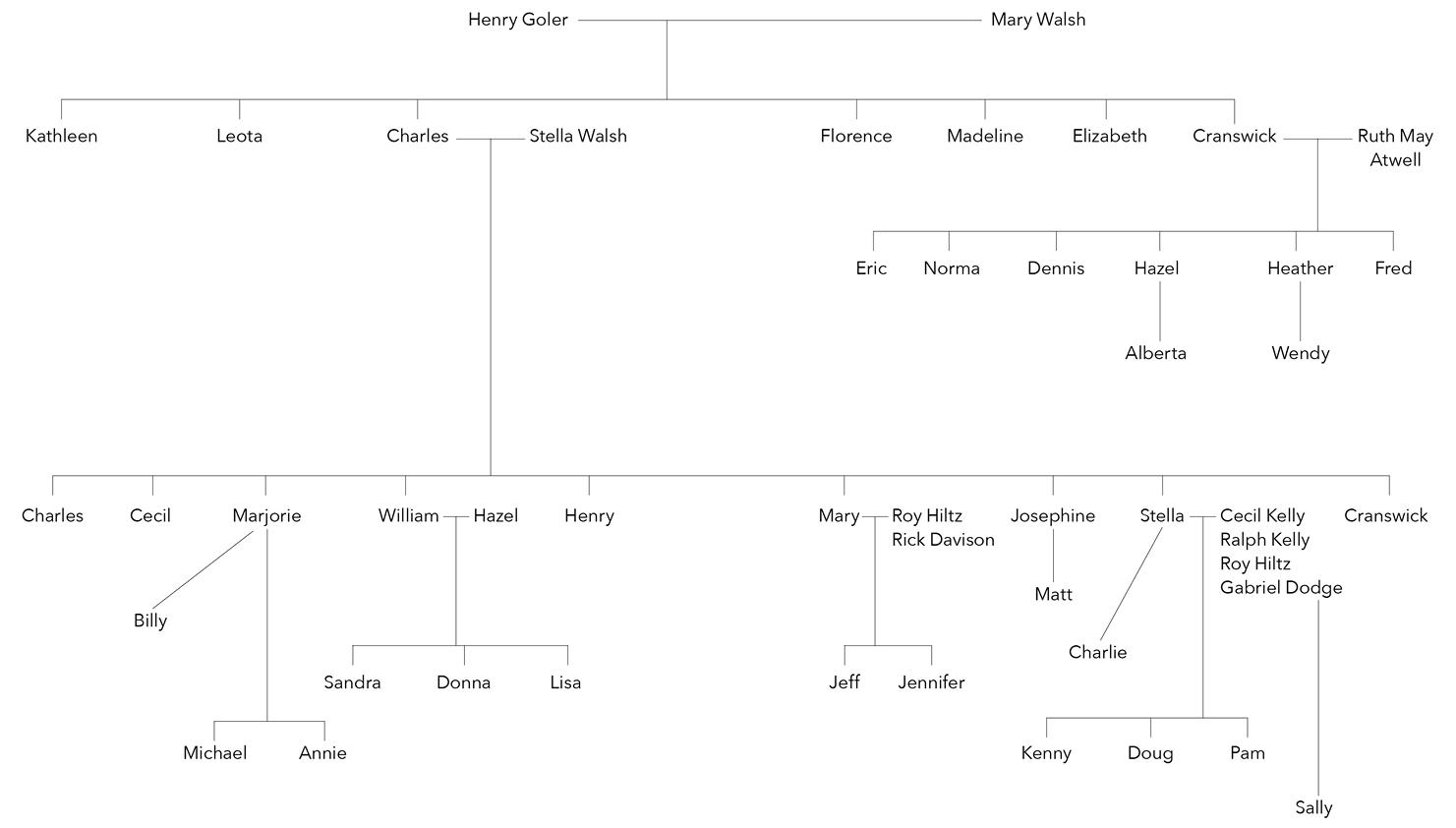

In the course of researching and writing this book weve made several decisions that we hope readers will understand and appreciate. The most difficult task we faced was tracking down the Goler children, then convincing them to talk. We were successful in finding them all. In two cases, the children had no recollection of their time on the Mountain. We chose not to disrupt their lives or spark unwanted recollections.

Several of the children have gone to considerable lengths to hide themselves and although they did talk to us, in the end they remained fearful of exposure. We have protected their anonymity by giving them all false names. We have also disguised the physical descriptions and location of any victims we felt could be discovered by reading this book. Regrettably, we felt obliged to disguise the names of three of the adult Clan members who were convicted because to identify them would have led to the children.

Prologue

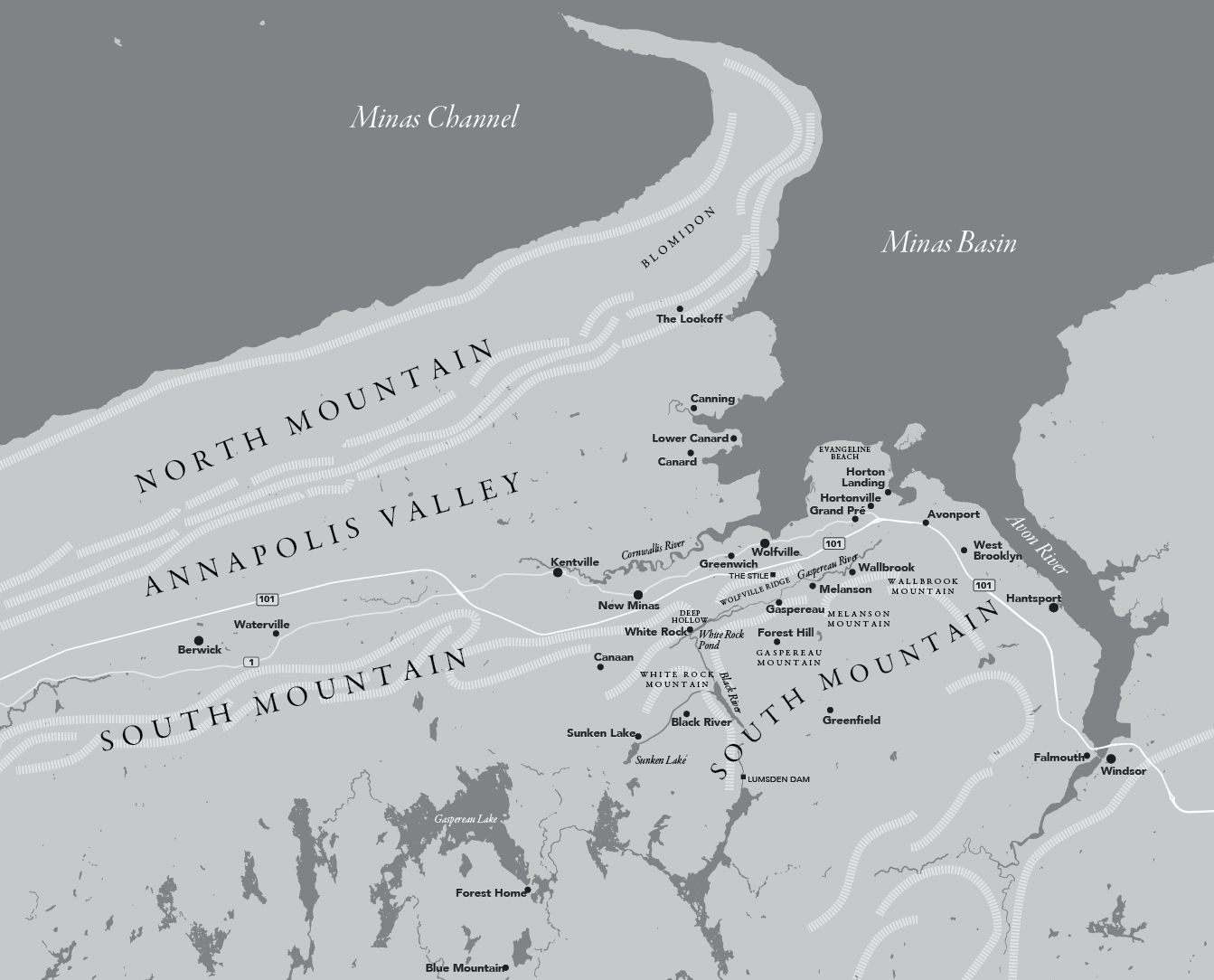

This book began in the late 1960s at my first school dance in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, and at my firstand laststoning. Stoningit sounds so biblical and righteous. In a way, I guess it was both.

A portion of the English-speaking population in the Annapolis Valley has its roots in the type of righteousness that can only be generated by a literal and extreme interpretation of a religious text. The New Light Planters of Connecticut, who displaced the exiled Acadians in the eighteenth century, were most definitely on the literal and extreme side of Bible adherents. The intolerance that grew out of their pinched and punishing world and after-world views created the conditions on South Mountain that led to the events chronicled in this book.

At the dance, the Love Street Disc band took a break. Id been thrilled to dance three times, though the boy who made my heart twist didnt even look in my direction. The teen I last danced with whispered, Dyou want to get high? I deeply and desperately wanted to do so. All the popular kids did, regularlyor so they said.

Ive often thought it ironic that as I worked hard to get stoned while choking on acrid marijuana smoke, I watched the stoning of seven teens from South Mountain, who had the temerity to attend the dance. Some older boys surrounded them shouting, Golers go home!

The four girls and three boys huddled together, refusing to leave. Then one rock flew, and another. It didnt take long to rout the interlopers. One of them might have been the father, mother, uncle, or aunt of the young woman, Donna Goler, who appears in this book.

The next day, I was on cloud nine after one of the boys I danced with offered a ride up the Mountain to see where the Golers lived. Wed only moved to Wolfville a few months earlier, and I had no idea where the Mountain was, what it represented and why everyone loathed, and perhaps feared, those who inhabited its rocky, unforgiving terrain.

I remember three things about that ride up the Mountain on the back of a Honda 125. First was the thrill of speeding up hills and leaning so deeply into the curves it seemed we would tip. Second was the intoxicating smell of a young mans back clad in a leather bomber jacket. Hang on! he shouted. I needed no encouragement. Third was a small shack, the exterior covered in tattered building paper flapping in the wind. Four children played outside. The front door hung open like a gaping mouth with nothing but dirt below and no steps leading up to it. Not far away a man crouched, defecating in a shallow depression. The boy driving the bike pulled an empty glass soda bottle out of his jacket pocket and threw it at the man, who shouted obscenities in our wake. We laughedwhat filth, and how exciting to find such primitives in our backyard!

Exciting, yes, but also haunting. During the rest of my two years in Wolfville, I heard many awful stories of the Mountain and the people who lived there. There were tales of babies born to mere children, horrible deformities, and gangs of witless men breaking into Valley homes and raping everyone. Good Valley girls who got knocked up went to the Mountain to lose their babies. Powerful moonshine could be had up there by those with the nerve to buy it. A case of beer was the price of banging a Mountain child. If someone dressed badly or said something stupid, the response was often, Dont be such a Goler!

Fifteen years after that dance, I was visiting my parents, who had returned to the Valley from Halifax and were living in Kentville, less than half an hour from Wolfville. My father had settled into life as a small-town lawyer. I was a mother and published writer and had begun to collaborate with my partner, David Cruise, on our first book. It was a warm summer day in 1983 when I set off for a run from my parents house. I headed into town on a ten-kilometre loop Id taken many times before. I circled around the courthouse at the halfway point and as I rounded the far side, what I saw brought me to a sudden stop. A group of handcuffed people, mostly men, formed a ragged line leading to the courthouse door. They were ill-clothed and dirty and there was just enough breeze to bring their sour odour to my nose.

I spotted a man I recognized from Wolfville in the gathering audience on the sidewalk. When I asked what was going on, he responded: A bunch of Golers banging kids, I heard. What dyou expect, huh? Nearly two dozen people from South Mountain had been arrested for various sexual crimes involving children. Images from the dance in 1968 assaulted me so powerfully I thought I was going to vomit right there on the sidewalk. I knew then, and probably long before, that I would have to write about the Mountain. But it would take more than a decade and four books before our publisher had confidence that David and I could tackle