THE PRIEST BARRACKS

GUILLAUME ZELLER

THE PRIEST BARRACKS

Dachau, 19381945

Translated by Michael J. Miller

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

This book is published on the recommendation of Jean-Louis Thiriot.

Original French title:

La Baraque des prtres: Dachau, 19381945

2015 by ditions Tallandier, Paris

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from Revised Standard Version of the BibleSecond Catholic Edition (Ignatius Edition) copyright 2006 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Front cover image:

Dachau KZ Denksttte / Wikimedia Commons Image

Back cover image:

Major concentration camps 1940-45 / Dachau / Liberation

NARA, College Park / Wikimedia Commons Image

Cover design by Enrique Javier Aguilar Pinto

2017 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-62164-099-8 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-766-2 (EB)

Library of Congress Control Number 2015953757

Printed in the United States of America

To Fanny.

In memory of Father Ren de Naurois (1906-2005),

Chaplain of the Kieffer commando,

Companion of the Liberation

CONTENTS

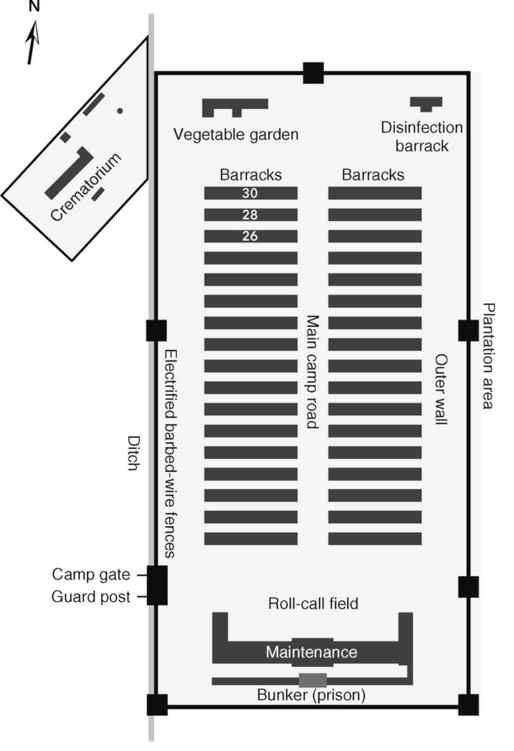

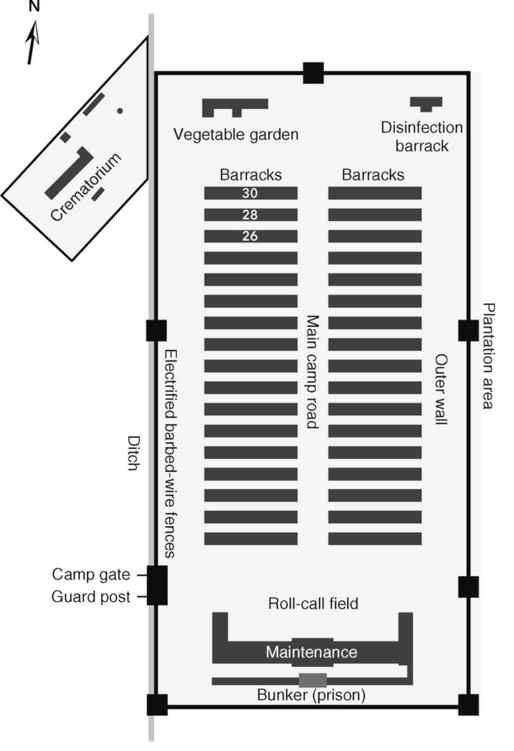

DACHAU CONCENTRATION CAMP

INTRODUCTION

Remember those who are in prison,

as though in prison with them.

Hebrews 13:3

Pawel, Alojzy, and Boleslaw were brothers. Born in Iwiczno, Poland, in 1893, 1896, and 1902, respectively, all three chose to dedicate their lives to God by becoming parish priests of the Diocese of Chelmno. In this region, which was long fought over by Germany and Poland, the first became priest of Gostkowo; the second, priest of Gronowo; and the third, vicar of Mokre. In the autumn of 1939, shortly after the defeat of Poland by the armies of the Third Reich, they were arrested by the Nazis, who were intent on killing the Polish elite. The three brothers ended up in a concentration camp in Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen, Boleslaw disappeared. Sixteen days later, on August 30, Pawel kept his promise and in turn died at Dachau.

The Prabucki brothers were just three of 2,579 priests, monks, and Catholic seminarians from the Reich and from all over occupied Europe who were imprisoned in the Dachau camp by the Nazis from 1938 to 1945. The story of these men is unrecognized, submerged in the overall history of the concentration camps. Furthermore, they are eclipsed by two major figures of Catholic martyrology who were murdered at Auschwitz: the Franciscan priest Maximilian Kolbe, executed on August 14, 1941, by a phenol injection after days in a starvation bunker, and the Carmelite nun Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, who was born Edith Stein, a convert from Judaism and former assistant to Edmund Husserl, gassed at Birkenau on August 9, 1942. Both have been canonized.

How many people know, however, that at Dachau two or three barracks out of thirty were permanently occupied by clergy from 1940 to 1945? Polish elite; German, Austrian, or Czechoslovakian political opponents; members of the Belgian, Dutch, French, Luxemburgian, and Italian resistancefrom all countries and of all ages, the priests were gathered behind the barbed wire of Dachau according to an agreement wrested from the Reich by Vatican diplomacy. For eight years, both tragedies and magnificent gestures punctuated the journey of the clergy at Dachau: from the terrifying forced march of Holy Week in 1942, to the heroic voluntary confinement of priests in the barracks of those dying of typhoid, to the moving, clandestine ordination of a young German deacon by a French bishop who tended to favor Vichy France and was later honored as Just among the Nations at the Yad Vashem Remembrance Center in Israel. Never in the course of history, even in the worst hours of the French Reign of Terror or Communist persecution, have so many priests, monks, and seminarians been murdered in such a small area: 1,034 gave up their lives.

Beyond the personal journeys of which it is composed, the history of the priests at Dachauto which we must add 141 clergymen of other denominations, the large majority of them Protestant and Orthodoxsheds new light on Hitlers system of concentration camps, on the intrinsic anti-Christian animus of Nazism, and, beyond the strictly historical perspective, on faith and spiritual commitment. How does the experience of the priests at Dachau compare to those of their comrades who were laymen? What were their privileges and what were their particular sufferings? Did the persecution undertaken by the Nazis against the clergy have ideological or political underpinnings? Did the faith and religious commitment of the priests reinforce them or render them helpless against the methodical dehumanization undertaken in the camps? Were their moral convictions, forged by the Gospel and the Tradition of the Church, able to resist the perversion of values imposed by the SS? Did the sufferings endured by the priests at Dachau bear fruit within the ecclesiastical institution and also outside, at the peripheries of the Church? Recounting this strange story, this fragment of the tragedy of the concentration camps, allows us to outline answers to these various questions.

Part One

A Camp for Priests

Chapter 1

The Precursors

O Lord, how many are my foes!

Many are rising against me.

Psalm 3:1

As the crow flies, seventeen kilometers northwest of Munich, a city sprawls, which has long been renowned for its unique atmosphere, conducive to the inspiration of artists. Since the end of the nineteenth century, many painters have converged there, seduced by the countryside and the light of its places. Some of them, such as Ludwig Dill, Adolf Hlzel, or Arthur Lanhammer, had lasting fame and started in Dachaufor this is the name of the commune prized by the musesa movement which rivaled the famous school of Worpswede. Besides the enchanting natural landscapes surrounding it, the city itselfthe first traces of which go back to the year A.D. 805shows evidence of urban planning and architecture well suited to fostering painterly creativity. This can be seen in the Church of Sankt Jakob, with its forty-four-meter-high tower topped by an onion dome looming over the town; in the Renaissance-style castle built in the mid-sixteenth century; or again in the old district with its joyously colored faades. As a cultural city, on the eve of World War II, Dachau was a place with a typically Bavarian and very attractive way of life.

Since the Middle Ages, Dachau had also been a commercial center, with mentions in documents of its market starting in the thirteenth century. The town had a strategic position on the route that linked Munich to Augsburg, at the border of a region of wooded hills to the north and marshy expanses to the south. This dynamic allowed it to overcome somewhat the force of gravity exerted by the Bavarian capital, which is visible from the heights of the city.

To the northeast of the historic center, on the other bank of the Amper, a munitions factory was built in 1916 to supply the soldiers of William II during World War I. The factory was not built in the town of Dachau, but in that of Prittlbach, situated north of it, on a tributary of the Amper from which it gets is name. However, over the years, the site became administratively attached to Dachau. Here, on the vast campus of this factorywhich was decommissioned after the defeat of the Kaiser the Nazis opened the prototype of their concentration camps on March 22, 1933.

Himmlers Model Camp

The day before, on March 21, Heinrich Himmlerwho led the Bavarian political policeannounced the opening of the Dachau camp during a local press conference.

Next page