First edition published in 2014 by Awa Press, Unit 1,

Level 3, 11 Vivian Street, Wellington 6011, New Zealand.

ISBN 978-1-927249-12-3

ebook formats

epub 978-1-927249-13-0

mobi 978-1-927249-14-7

Original text Estate of Jack Elworthy

This edited text Jo Elworthy

Court of Enquiry, October 30, 1945 New Zealand Defence Force

The right of Jack Elworthy to be identified as the author of this work in terms of Section 96 of the Copyright Act 1994 is hereby asserted.

This ebook is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of coding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

Cover photograph courtesy Das Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-166-0509-14 / Photograph: Weixler, Franz Peter

Cover design by Ceri Hurst

Ebook conversion by Harriet Prebble

Produced with the assistance of

Find more great books at awapress.com

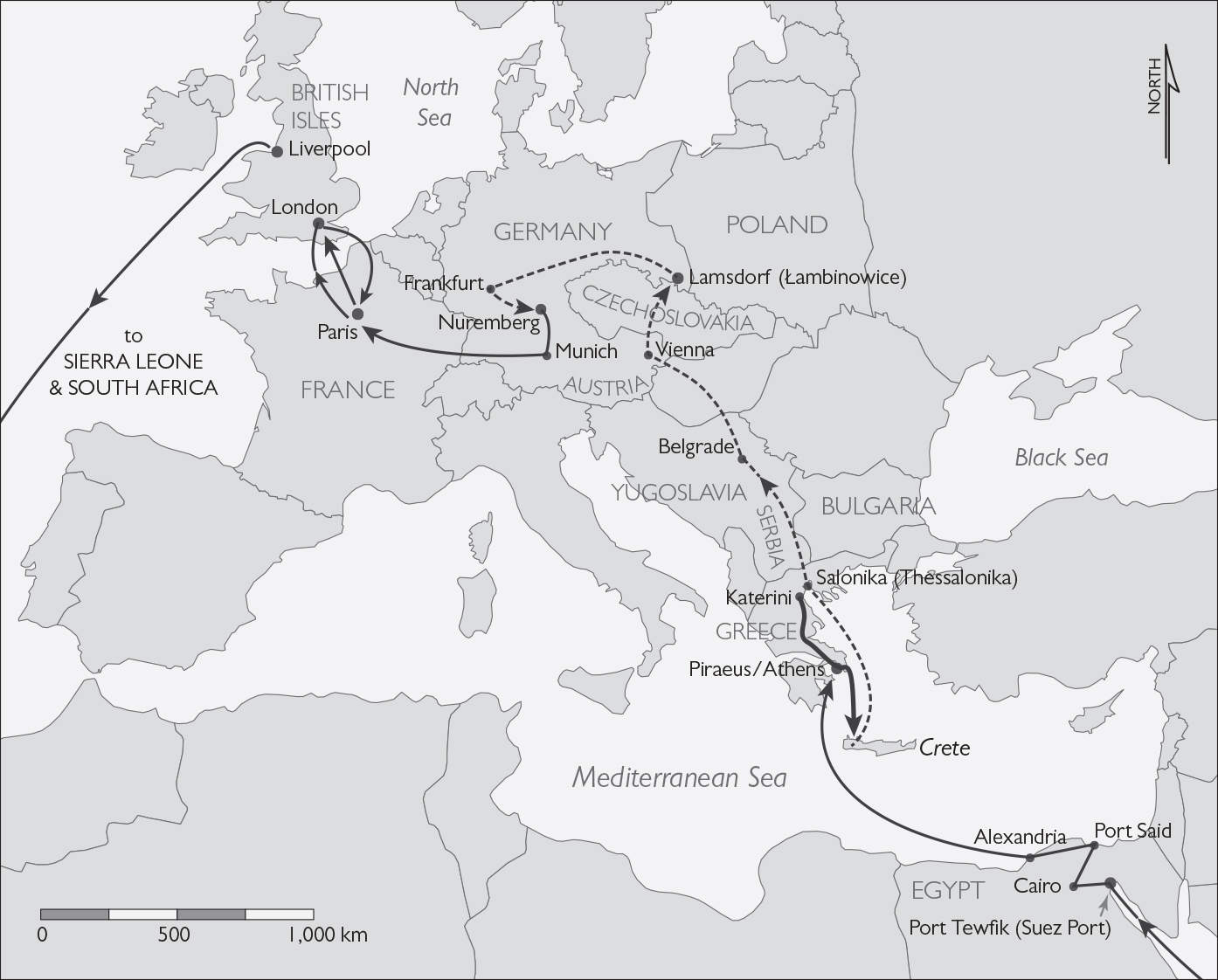

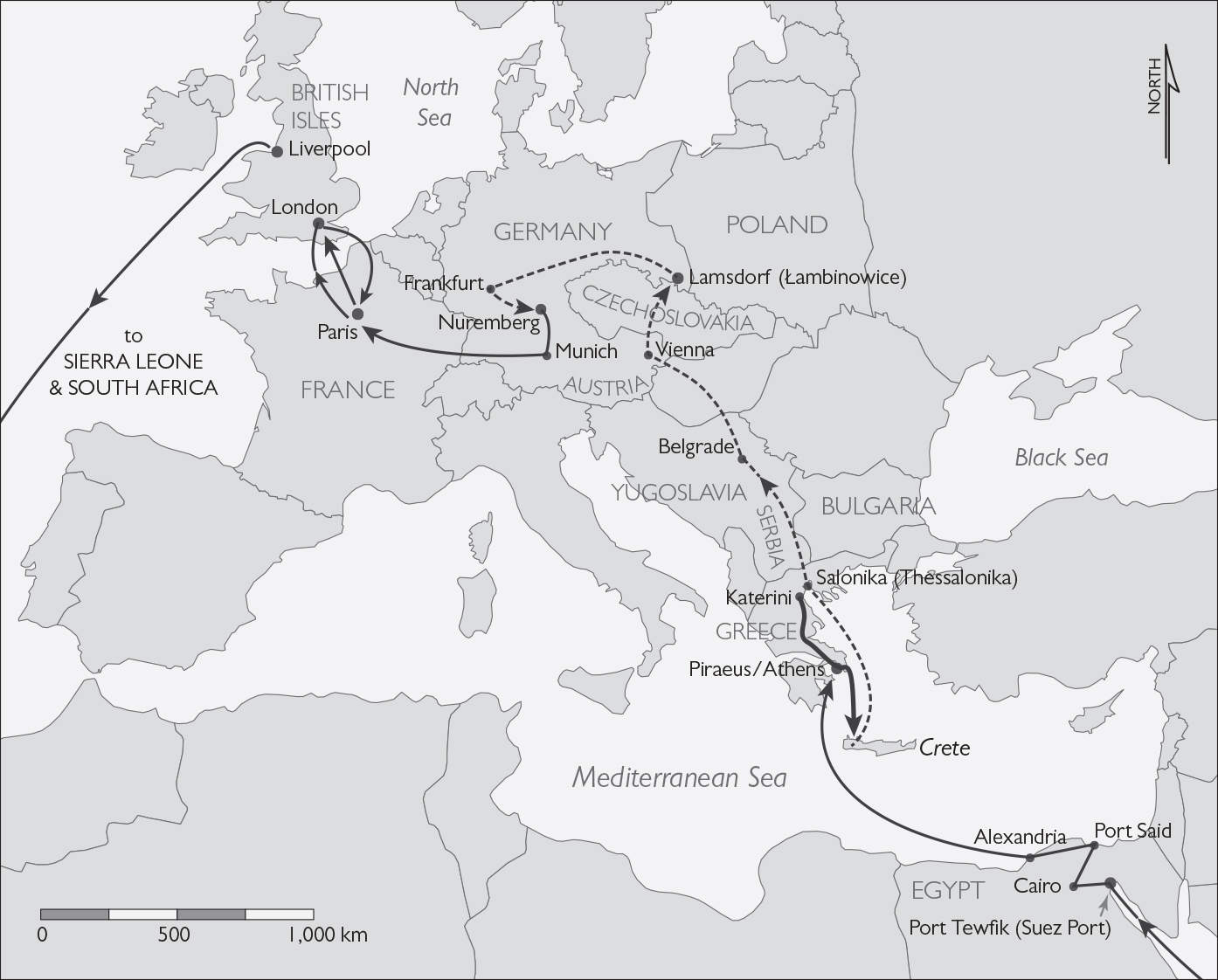

Map of Europe and North Africa 194145, showing Jack Elworthys journey as a soldier. The dotted line indicates his transportation as a prisoner of war.

For my children and their children

in case they might one day be interested

JACK ELWORTHY was born in Wellington, New Zealand in 1912. In 1935 he joined the New Zealand Permanent Force as a professional soldier and in May 1940, eight months after New Zealand declared war on Germany, sailed for Europe with the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force. He returned to New Zealand in 1947 and remained with the army until 1956, when he joined the Probation Service. He retired in 1977 and set about writing this book, drawing on his war diaries. He died on January 3, 1999.

His war record:

New Zealand Army: WO1 22820

Unit: 16th LAD attached to 5th Field Regiment

2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force

Sailed: Second Echelon

Prisoner of War: 24202

Stalag VIIIB (344) 19411945

Stalag XIIID 1945

Foreword

I first met Jack and Lilian Elworthy more than 30 years ago while working as a researcher in the television documentary unit based at Avalon in Lower Hutt. I was developing a story on the personal impact both on the POW himself and on his family back home of being a prisoner of war in the Second World War. I was influenced by the experience of my uncle who spent four years as a POW and came back to a wife and child he hadnt seen for five years. Jack and Lilians story, however, was more extreme because it was nearly seven years before Jack returned to New Zealand.

Like the other Kiwis who went overseas in the war, Jack never expected to be a POW. As a professional soldier he knew he might be wounded or even killed, but being captured was not in the equation. Fewer than a hundred of our men had been taken prisoner in the Boer War and just over 500 in the First World War, less than one percent of the number of our total casualties in that terrible conflict.

Yet more than 9,000 New Zealanders became prisoners in the Second World War, most of them soldiers in the Second New Zealand Division. Nearly all of these men were captured in Greece, Crete and North Africa between April 1941 and July 1942, when the division was involved in a series of Allied debacles.

Jack had the bad luck to be caught up in the worst disaster, the defeat on Crete in May to June of 1941. This was a battle in which New Zealand commanders played the key roles, right up to the top. Some of these officers made a series of poor decisions that led directly to the defeat.

The soldiers at Jacks level, however, knew nothing of this and simply did their best. There were many casualties. As Jack explains, in the chaos and confusion of the battle he was taken prisoner twice, initially on the first day of the battle after which he was soon released and then 12 days later, when the forces left behind on the south coast surrendered. He was one of more than 2,000 Kiwis (along with Australian, British and Greek soldiers) who ended up in makeshift prisoner-of-war camps on Crete and later on the Greek mainland. Ultimately, Jack and many other prisoners were sent on to Stalag VIIIB, a large camp in Silesia.

When these prisoners were finally released during the Allied advance into Germany in 1945, most of them simply wanted to go home. However, a few, like Jack, decided to make up for their years in captivity by re-entering the fray. This was against the policy for POWs but Jack found a friendly American unit who let him join in the last weeks of the European war. Once again Lilian at home was told that her husband was missing, believed killed.

Eventually Jack returned to New Zealand and an uneasy adaptation to work and home. Like many ex-prisoners, his experiences had deeply affected him and he found it hard to fit into a peacetime existence. By the time I met him he had left the army behind him and had gained a clear perspective of the effect, on both him and his family, of his years away.

Unfortunately, the television documentary did not come to fruition, but we passed the idea on to the radio arm of the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation, where it was turned into an excellent programme.

Jacks story, told in his own words and being published more than 70 years after the battle for Crete, is a reminder of the profound physical and psychological upheavals suffered by New Zealand soldiers in wartime, and the brutal reality for those taken prisoner.

David Filer

David Filer is a writer and researcher specialising in military history. Among his published works are Prisoners of War in The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Military History and Crete: Death from the Skies , a book on New Zealands role in the loss of Crete.

Preface

This is an unvarnished story of the Second World War through the eyes of a young soldier. My father Jack Elworthy was one of 140,000 New Zealanders who served overseas between 1940 and 1945. When war came he was a 27-year-old warrant officer, newly married, and excited about the opportunity for adventure on the other side of the world. When the adventure was over and he came home, he had been changed forever.

When New Zealand declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, Jack was a member of the countrys small regular army, known then as the Permanent Force. Eight months later, in May 1940, he said goodbye to his wife and baby son and sailed from Wellington with the Second Echelon of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. As a member of the 16th Light Aid Detachment, he was transported with the 5th Field Regiment to England, Egypt, Greece and Crete. In May 1941, he was captured on Crete and sent as a prisoner of war to Stalag VIIIB (344) at Lamsdorf in Silesia, Germany. Later he was moved to Stalag XIIID in Nuremberg.

When advancing United States troops liberated Stalag XIIID in April 1945, he unofficially joined a field artillery battalion of the United States 7th Army and travelled with the American troops around Germany until July 1945, when he made his way to England to await repatriation.

It would be another two years before he arrived back in New Zealand. The son who had been a baby when he left was by then seven years old. Jack and his wife Lilian went on to have two more children, my sister Juliet and me. He retired from the New Zealand Army in 1956 and had a second career as a probation officer. He died in 1999.