They traveled far from the homes and families they loved .

they not only served their country, they saved the world .

They say that the birds never sing at Dachau. Perhaps they cannot produce their wondrous music in a place that has witnessed such tragedy, such cruelty, such horror. Perhaps God forbids it. Or perhaps, on their own, they are muted by the profound sense of sadness that permeates the very air around Dachauair that once was filled with the cries of innocents and the lingering smoke of their ashes .

In my life, I have been blessed beyond measure with a loving family and staunch friends. For more than thirty-five years the people of my home state entrusted me with the privilege of representing them in Washington. Twice my party has nominated me for the highest office in the land. Yet, no honor that has been bestowed upon me has engendered greater pride than that of wearing my uniform in the service of my country.

When America was called upon to rise up against the tyranny and the almost unthinkable atrocities of the Nazis and their allies, an entire generation responded. Ordinary men, like Jack Saccos father, Joe, myself, and thousands more rallied to the cause and found ourselves facing hardships the likes of which we had never imaginedand we won.

Some sixty years later, we have been called the Greatest Generation, but our ranks are slowly thining. But just as our cause was worth fighting for, so too are our stories worth remembering. Jack Sacco has paid his father and all those who have ever served this country the ultimate tribute. Where the Birds Never Sing is an honest, moving portrait of his father, an American soldier in World War II, who fought for everything that makes our nation great.

This book does not glorify warfar from it. For no one knows better than a soldier that war is in many ways the worst of mans creations. Yet there are principles worth defending and evils that must be stopped. In doing so, the greatest qualities of which human beings are capable emerge: courage beyond measure, loyality beyond words, sacrifice, ingenuity, endurance, and a love of country and fellow man that is truly boundless.

Thanks to men like Jack Sacco, Americans will never lack for stories of heroes. And thanks to men like his father, Joe, well never forget how heroes are made.

-Senator Bob Dole

When I was a boy, my father often told me stories about the war. I would listen with wide-eyed fascination as he recounted tales of how he and his buddies fought their way across Europe under the leadership of General George S. Patton. He showed me Nazi swords, daggers, and other artifacts he had collected as his battalion stormed through France and Germany. But there was more to the story than he could share with such a young boy.

One day, just after my twelfth birthday, he called me into the family den and asked me to sit with him and my mother. He pulled out a small photo album. Im going to show you something that happened during the war, he said. He glanced at my mother, who cautiously nodded that it was okay for him to open the book. I didnt want you to see these until you were old enough, he continued. My buddies and I took them the day we liberated the concentration camp at Dachau.

Concentration camp? I asked.

Yeah, he answered. The Nazis killed people there. But we made them stop.

He opened the album and handed it to me. Inside I saw horrific images of suffering, cruelty, and death, the likes of which I could have never imagined. I stared at each picture in disbelief, turning the pages slowly as he told me the story of what had happened on April 29, 1945. The unspeakable horrors caught on film, he said, were only a glimpse of what he had witnessed when he entered the camp.

In the years that followed, I came to realize that the events of that day had had a profound impact on his life, forever changing the way he would view the world and forming in him a steadfast resolve that good must always find a way to overcome evil.

Shortly after I graduated from college, he made copies of the photos for me and my siblings. Occasionally I would pull them out for friends who wanted to see a piece of history, describing the events as my father had described them to me. I found that the pictures, themselves a sobering remembrance of the Holocaust, became even more powerful when framed by the story of the men who had taken them. In having them published here for the first time, it is not my goal merely to present them for shock value, but rather to recount the sacrifice, courage, and honor of the American soldiers who liberated the camp, and to explain that these menthese liberatorswere actually boys, barely out of their teens, who had survived the most historic battles of the twentieth century.

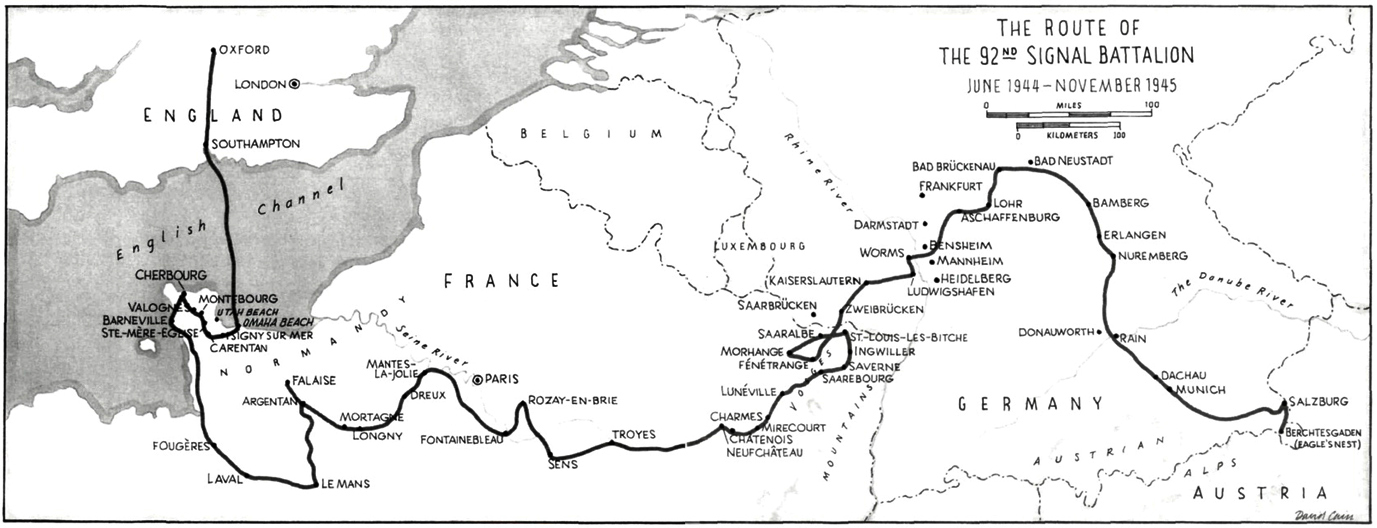

Even though I already knew the most important elements of my fathers wartime journey, I interviewed him and his buddies extensively about their experiences before I began the process of writing this book, filling in gaps in the story as I tracked their progress across Europe. Wars, by their very nature, are extraordinarily complex events involving thousands and thousands of people. In order to clarify what could have become a confusing and dry narrativeand so as not to embarrass any of the good men of the 92nd Signal BattalionI took the common artistic liberty of combining some characters and events and changing a few names when it was appropriate. This helped simplify the story without sacrificing the integrity, emotion, or adventure for the reader. The result was a moving (and often surprising) account of what it was like for the American soldiers in World War IIof how it felt to be fighting a war so far from home, uncertain of their fate and, more often than not, unsure of their true mission.

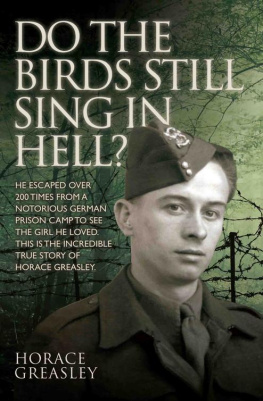

Though they were ultimately victorious, the war took an emotional and physical toll on the young soldiers. The photograph of my father on the cover of this book was taken in Salzburg, Austria, one week after the liberation of Dachau. He was twenty years old. Behind his pleasant features and slight smile, his eyes seem to hold the weight of what they had witnessed only days before, echoing a quiet sadness that, even to the end of his life, could still cause them to well up with tears.

Joe Sacco was the only child of immigrant parents. He worked on the family farm and, like many of the young soldiers of World War II, had never been away from home before being drafted. He had never held a weapon more powerful than a BB gun. He had never witnessed violence more intense than a schoolyard fight. And the first beach he ever saw was Omaha Beach at Normandy. His is the story of how an innocent farm boy from Alabama left home, trained with the U.S. Army, fought his way through Nazi-occupied France and Germany, and eventually helped put an end to the Holocaust.

He told me that for several years after the war, he would not speak about the atrocities hed seen. He didnt think anyone would be able to fully understand the magnitude and significance of what he and his buddies had experienced. His eventual decision to show me and my siblings the photographs of Dachau, therefore, was not made lightly. He knew that the images were frightening, but he thought it important for his children to see what hed witnessed firsthand so many years beforethe shocking cruelty that had taken place in the Nazi concentration camps. And he wanted us, through his witness, to stand vigilant against such inhumanity ever being allowed to happen again.