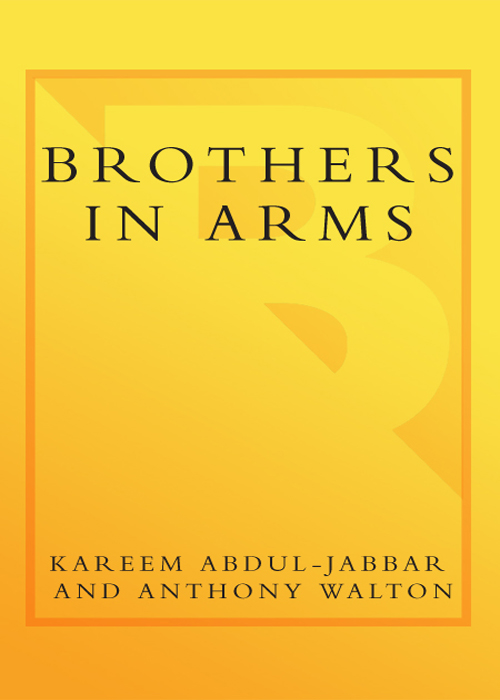

BROTHERS

IN ARMS

The Epic Story of

the 761st Tank Battalion,

WWII's Forgotten Heroes

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

and Anthony Walton

BROADWAY BOOKS | NEW YORK

Contents

To Colonel Paul Levern Bates

and the men

of the 761st Tank Battalion

Men, you are the first Negro tankers to ever fight in the American Army. I would never have asked for you if you weren't good. I have nothing but the best in my Army. I don't care what color you are, so long as you go up there and kill those Kraut sonsabitches. Everyone has their eyes on you and is expecting great things from you. Most of all, your race is looking forward to your success. Don't let them down, and, damn you, don't let me down!

GEORGE S. PATTON, NOVEMBER 2, 1944

NEAR NANCY, FRANCE

Preface

Leonard Smitty Smith was a Transit Police officer with my father, F. L. Al Alcindor, for more than two decades, beginning in the mid-1950s. They were good friends, and would often hang out together after they had finished their shifts. Sharing an enthusiasm for the Big Band sounds of their youth, they most enjoyed going to the jazz clubs together to hear Lionel Hampton, Count Basie, Benny Carter, Maynard Ferguson, and the Thad JonesMel Lewis Big Band.

Smitty was like a surrogate uncle to me. He is one of those people who has an intense opinion on just about any subject and he is never reluctant to share his views. The district office for the New York City Transit Authority Police in upper Manhattan was located at the 145th Street subway station, and I would often have to change trains there to get to whatever game I was playing in the Bronx. My Dad had asked Smitty and other fellow officers to keep an eye out for me, to make sure that I didn't get into any of those minor schoolboy hassles that occasionally turn ugly. Many a time Smitty would suddenly materialize at my side as I waited on the platform. His first words to me were always Hey, young man. We would chat while I waited for my train. He would ask about my grades or how my Mom was doing, or wisecrack about how badly the Knicks were playing.

On one occasion, some of my friends were riding with me to check out that evening's game. Smitty gave them the once-over and told my friend Little Bob that should any trouble start, he wouldn't hesitate to shoot whoever was involved. Little Bob, not knowing Smitty's playful nature, took him seriously. He told Smitty that shooting a kid would get him fired from the police force. Smitty replied that Little Bob would be dead and so wouldn't get any satisfaction from that fact. It was a couple of days before I could convince Little Bob that Smitty had been pulling his leg.

Black men on the New York City police force were unusual in the 1950s. My Dad, Smitty, and the few other blacks in the Transit Police were pioneers. They had to endure the critical eyes of the public, the hostility of some of the white cops, and occasionally the resentment of black people who felt that they were sellouts. The fact that they were eventually able to earn the respect of both the police hierarchy and the black community says a lot about their achievement. My Dad went on to become a sergeant, and later a lieutenant, advancing through the ranks: Smitty was always supportive; he was proud to see a black cop take up the challenge and succeed.

Smitty's personal story never surfaced while he and my Dad were on the force together. Although he was a friendly face and welcome presence, I saw him as a grown-up; it never occurred to me that he even had a story. I never thought to ask about his life. I had no idea that Smitty, years before, had been a pioneer in an even more significant context.

WHEN I MOVED OUT TOCalifornia to attend UCLA and later to play for the Lakers, I didn't see Smitty for many years. All that changed one night in 1992 at Lincoln Center. The lights had just been dimmed, and I was rushing to find my seat in the concert hall. The featured event was a documentary film about a black tank unit that had fought in WWII. I had been enlisted to assist in a number of public-speaking appearances in which members of the unit would describe their combat experiences. I'd been interested for some time in the struggle of black veterans to gain the recognition they deserved, in part because of my father's experience in the Army.

Dad was trained in artillery at Fort Braggspecializing in the 155mm howitzerand was qualified and eager for an opportunity to fight the Germans. But like many African Americans in what was still a segregated Army, he never got that chance. Most blacks were allowed only to train; it was hoped that this limited gesture would be enough to ensure the black community's support for the war effort. Accepting the inevitable, my Dad chose to serve in a band unit and never left the States for the duration of his tour of duty. His experience in the Army had another, unexpected benefit, however, because it was during his military service that he met my Mom. He always said it was the high point of his time in uniform.

African Americans in support roles performed important tasks from the outset of the war, including loading convoy ships, carrying out mess duties, driving supply trucks and ambulances through combat zones, and constructing military highways. Later, as Allied casualties mounted and replacements became an issue, some African American units were finally given the chance to fight. The 761stthe heroic tank battalion chronicled in the documentary film I was about to watchwas one of these units.

One special aspect of the 761st's role in the war concerned their involvement in the liberation of some of the Nazi concentration camps. That night at Lincoln Center, Harlem Democrats Percy Sutton and Charles Rangel, who both served with the Tuskegee Airmen, were in attendance, as were such notables as Lena Horne, Roy Haynes, Sidney Lumet, Dr. Ruth Westheimer, and other highly regarded members of New York's black and Jewish communities. As I hurried to my seat, I heard an oddly familiar voice call out, Hey, young man. Something about that voice transported me back in time, to my teenage years. I turned, and there was Leonard Smith.

What are you doing here? I asked him in surprise. Smitty replied that he had been a member of the 761st. With the lights flickering on and off, signaling the imminent start of the film, we had to get to our separate seats. Running into Smitty after all those years was a pleasant shock. But what I saw in the film left me speechless. Smitty had been involved as a tank gunner in some of the most intense fighting of World War II. He had fought in five countries and had been awarded a Bronze Star for valor.

When I found Smitty after the screening, I was unable to adequately express how deeply I'd been affected by what I had just seen. Being exposed to a side of a person you've known that has been hidden or ignored for so long can be very disorienting. Smitty had never mentioned his war record, even to my Dad. In the years since I learned of his service, I've come to find out that many soldiers, both black and white, who returned from the war never mentioned the ordeals they faced in combat. They all seemed to feel that they were just doing their jobs and deserved no special acknowledgment for performing their duty.

Unfortunately, some of the events referred to in the documentary I saw that night, Liberators: Fighting on Two Fronts in World War II, had not been adequately researched. The film was produced with the best of intentions, but crucial facts were incorrect or transposed. The resulting controversy tarnished the record of one of the most highly decorated and courageous combat units in the war, and made me aware of the need to tell the 761st's story in a way that would attempt, insofar as possible after almost sixty years, to set the record straight.

Next page