This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1958 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

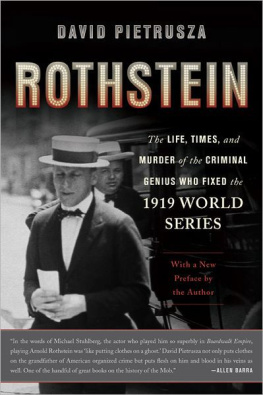

THE BIG BANKROLL:

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF ARNOLD ROTHSTEIN

BY

LEO KATCHER

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENT

It is now some twenty-five years since I first interested myself in the life and career of Arnold Rothstein. I had known of him earlier, of course.

It was when I went to work as a reporter on the New York Post that I began to wonder about what manner of man he was. In Center Market Place, behind police headquarters, I heard tales of Rothsteins influence and power from reporters who had known him, covered stories in which he was a central figure, observed him as a contemporary.

To these men, the real professionals among reporters, Arnold Rothstein was already a symbol, a legend, in the early 1930s. Joe Murphy, of the Times, Bob Barke, of the Mirror, Johnny Martin, of the News, Frank Roth, of the Sun, all talked of him as if he had ruled a supergovernment in New York.

Later, as reporter and editor, I began to get that same feeling about Arnold Rothstein. His body was in a grave, but his influence was a real, live quality in New York City. His name recurred, time after time, in newspaper stories.

He was as newsworthy in 1935 as he had been in 1925.

The election of Fiorello LaGuardia, who ran almost as much against Rothstein as against Tammany Hall, the Seabury Investigation, the Dewey onslaught on organized crime, all concerned themselves with this long-dead man. It came to me that the world in which I lived was partially shaped by him.

I wanted to learn more and more about him so that I could fit him into his proper place in the social history of our times.

I got to know Gene McGee and Maurice Cantor and asked them to tell me about him. Interviewing Lucky Luciano in Dannemora Prison, I asked him to talk as much of Rothstein as about himself. I searched the files of the New York Post and used its wonderful morgue. I owe a great deal to Peter Dinella and his staff for their help.

It was about ten years ago that I decided to write this book. In those years I have interviewed dozens of persons, read scores of books and hundreds of old newspapers. I talked with Murray Stand and James D. C. Murray. I interviewed Grover Whalen. I spent hours talking with Herbert Bayard Swope.

I talked with Ernest Cuneo and with Leo Spitz.

I had a long series of interviews with Carolyn Rothstein Behar, Arnold Rothsteins widow.

I spent many hours with Nicky Arnstein, whom I unashamedly like.

There were many others to whom I spoke, whom I interviewed. Some would talk only if I promised them anonymity. Others would not talk at all, looking over their shoulders as they refused me information. In almost every instance I found great reticence. A quarter of a century and more after Rothsteins death there were many persons unwilling to commit themselves about him.

It seems to me that this proves my basic premise: that the influence of Arnold Rothstein lives on, still survives.

All the conclusions reached in this book are mine. I have used the information given me, but the interpretation of that information is my own responsibility. What I sought were facts. How these facts were fitted into the complete picture was a matter of my judgment alone.

So, to all those who were willing to let me make public acknowledgment of their help, I now say, Thank you. Those who asked that they remain anonymous, them also I thank.

A special debt is owed to Allen Marple for reasons too many to enumerate.

And to my wife, who helped me prepare this book from thousands of pages of drafts and hundreds of pages of notes, all my gratitude.

LEO KATCHER

Los Angeles , 1958

Chapter 1Gunshot Wound (Fatal)

At 10:53 p.m., Sunday, November 4, 1928, the desk sergeant at the old West Forty-seventh Street station house in New York, received a call from a police box informing him of a shooting. He immediately wrote a short bulletin, transmitted it to police headquarters on Centre Street. It read:

Man reported shot in Park Central Hotel, Seventh Avenue and Fifty-sixth Street. Ambulance dispatched.

Shortly before midnight, more details having been given the sergeant, he wrote a second report, which went into the station house blotter:

Arnold Rothstein, male, 46 years, 912 Fifth Avenue, gunshot wound in abdomen, found in employees entrance, Park Central Hotel, 200 West Fifty-sixth Street. Attended by Dr. McGovern, City Hospital. Removed to Polyclinic Hospital. Reported by Patrolman William M. Davis, shield #2493, Ninth Precinct.

At 10:53 A.M., Tuesday, November 6, while millions of Americans were casting the votes that elected Herbert Hoover president, some changes were made in this second report.

The word fatal was parenthetically inserted after gunshot wound, and a second paragraph was appended:

Rothstein apparently had been engaged in a card game with others in room 349, on the third floor of the Park Central Hotel, when an unknown man shot him and threw the revolver out of window into street. Body found by Lawrence Fallon, 31-64 Thirty-fourth Street, Astoria, employed as house detective by the hotel.

This report was limited to the little knowledge possessed by the man who wrote it. It contained one major error. Rothstein had not been involved in a card game just prior to his shooting. He had, however, been involved in one a few weeks earlier and his shooting came as the direct result of that game.

The desk sergeant, even had he known this fact, would not have revealed his knowledge. He had good reason for being circumspect. If he knew nothing else, he knew that the shooting of Arnold Rothstein was a matter for the upper echelons of the police department, of New York City politics, and of local and nationwide crime and gambling.

Arnold Rothstein was much more than an ordinary citizen. He was The Brain, The Bankroll, The Man Uptown. His connections came from the top and went to the top, with Rothstein a central switchboard, a one-man nerve center. No ordinary desk sergeant wanted anything to do with Arnold Rothstein. Not with Rothstein alive nor, now, with Rothstein dead.

Of course, during the thirty-six hours between the first report and the last one, the shooting was being investigated. Detectives were not seeking information about Rothstein, because they knew all it was good for them to know. They wanted information about his movements on the windy, sleet-laden Sunday night when he was shot.

Next page