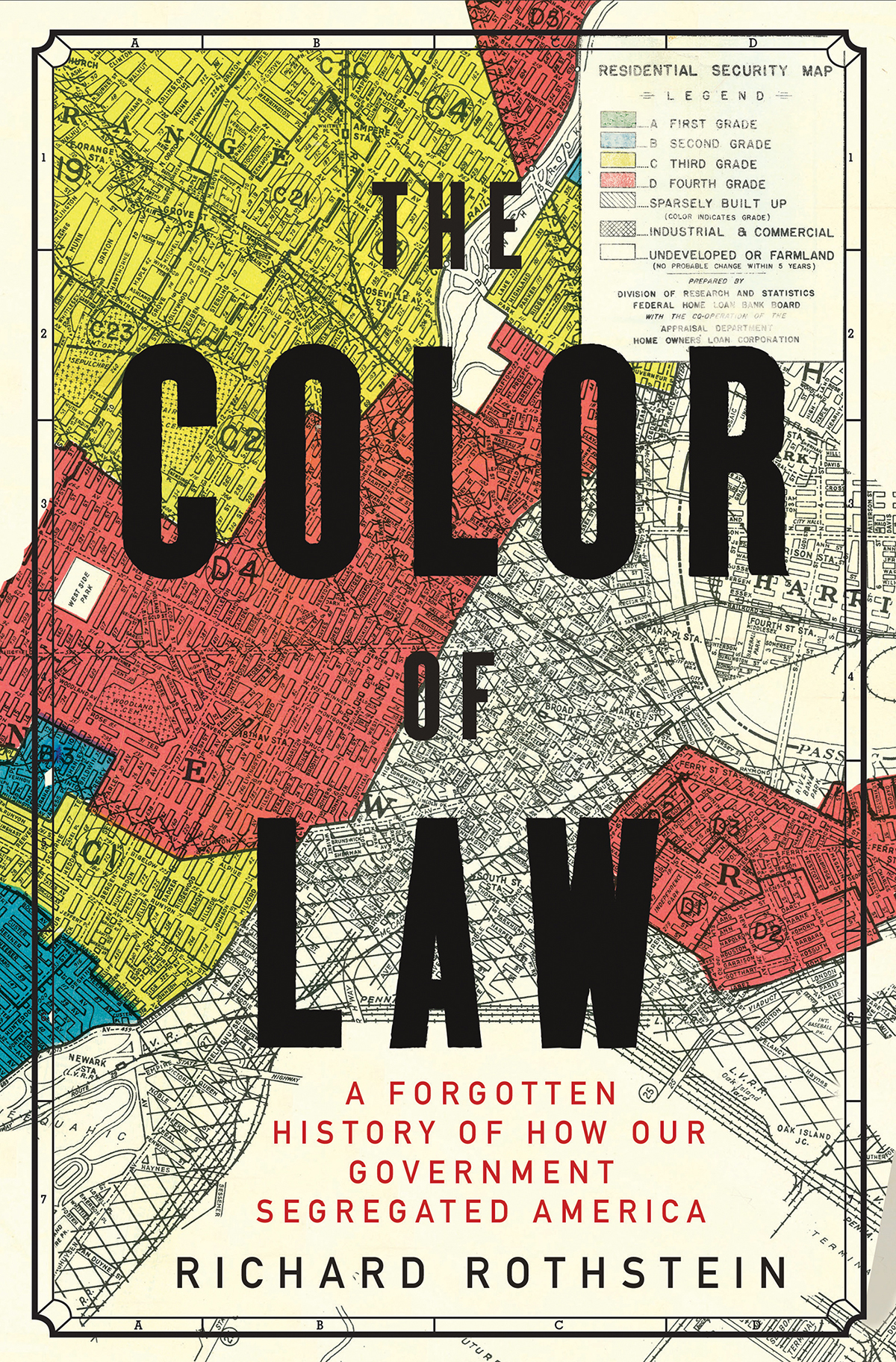

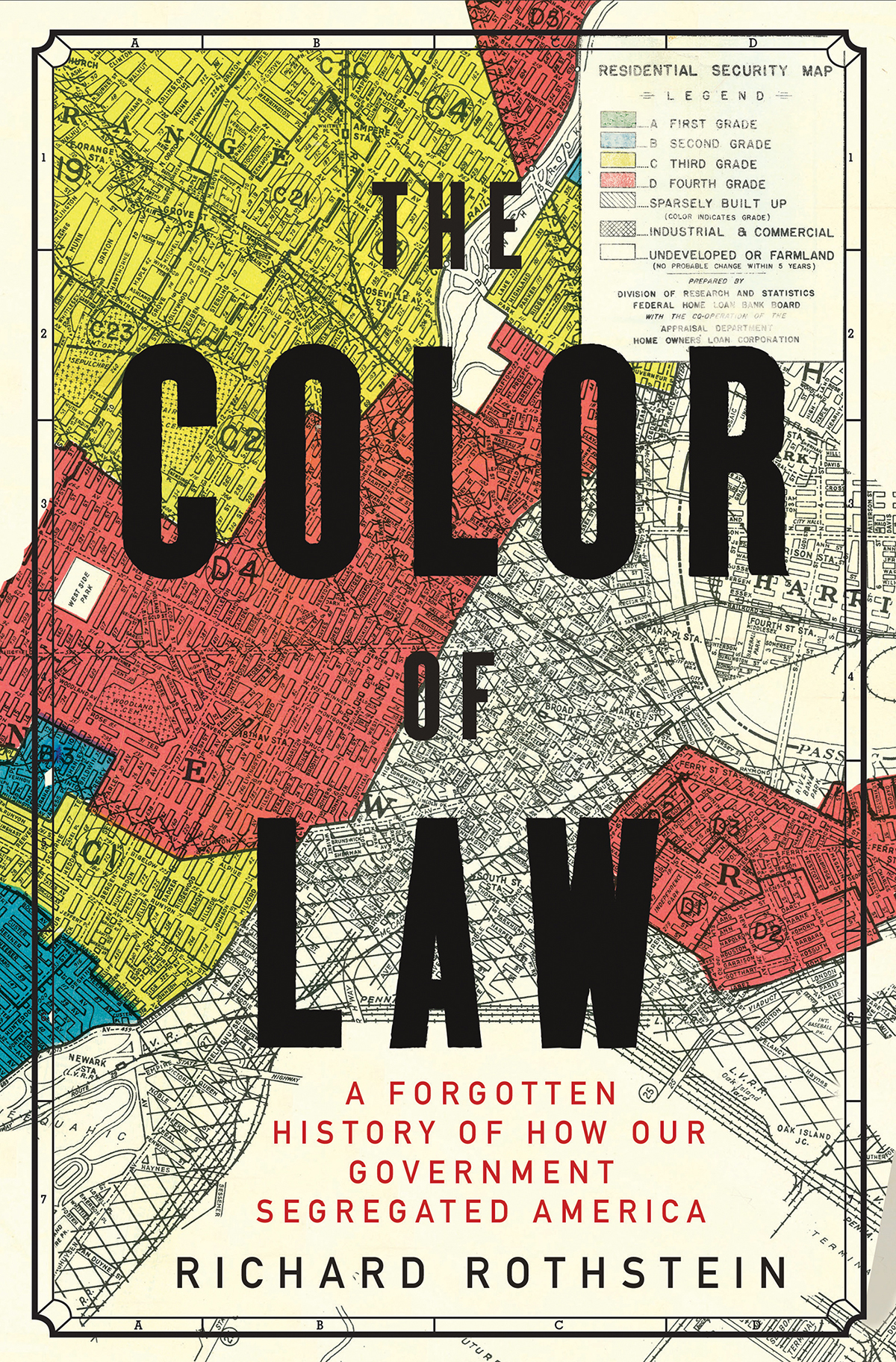

Frontispiece: Pittsburgh, 1940. President Franklin D. Roosevelt hands keys to the 100,000th family to receive lodging in the federal governments public housing program. Most projects were for whites only.

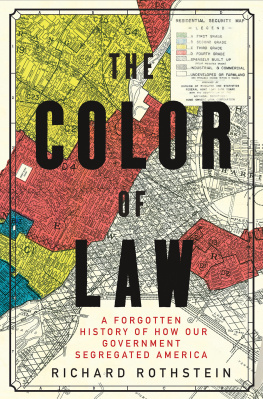

THE COLOR

OF LAW

A FORGOTTEN HISTORY OF

HOW OUR GOVERNMENT

SEGREGATED AMERICA

RICHARD ROTHSTEIN

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A Division of W. W. Norton & Company

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS SINCE 1923

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 2017 by Richard Rothstein

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this

book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation,

a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at

specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Brooke Koven

Production manager: Anna Oler

JACKET DESIGN BY STEVE ATTARDO

JACKET ART: ESSEX COUNTY, NEW JERSEY, JUNE 1ST, 1939; COURTESY OF LADALE

WINLING / URBANOASIS.ORG / HOLC MAPS

ISBN 978-1-63149-285-3

ISBN 978-1-63149-286-0 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.,

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

CONTENTS

W HEN, FROM 2014 TO 2016 , riots in places like Ferguson, Baltimore, Milwaukee, or Charlotte captured our attention, most of us thought we knew how these segregated neighborhoods, with their crime, violence, anger, and poverty came to be. We said they are de facto segregated, that they result from private practices, not from law or government policy.

De facto segregation, we tell ourselves, has various causes. When African Americans moved into a neighborhood like Ferguson, a few racially prejudiced white families decided to leave, and then as the number of black families grew, the neighborhood deteriorated, and white flight followed. Real estate agents steered whites away from black neighborhoods, and blacks away from white ones. Banks discriminated with redlining, refusing to give mortgages to African Americans or extracting unusually severe terms from them with subprime loans. African Americans havent generally gotten the educations that would enable them to earn sufficient incomes to live in white suburbs, and, as a result, many remain concentrated in urban neighborhoods. Besides, black families prefer to live with one another.

All this has some truth, but it remains a small part of the truth, submerged by a far more important one: until the last quarter of the twentieth century, racially explicit policies of federal, state, and local governments defined where whites and African Americans should live. Todays residential segregation in the North, South, Midwest, and West is not the unintended consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law or regulation but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States. The policy was so systematic and forceful that its effects endure to the present time. Without our governments purposeful imposition of racial segregation, the other causesprivate prejudice, white flight, real estate steering, bank redlining, income differences, and self-segregationstill would have existed but with far less opportunity for expression. Segregation by intentional government action is not de facto . Rather, it is what courts call de jure : segregation by law and public policy.

Residential racial segregation by state action is a violation of our Constitution and its Bill of Rights. The Fifth Amendment, written by our Founding Fathers, prohibits the federal government from treating citizens unfairly. The Thirteenth Amendment, adopted immediately after the Civil War, prohibits slavery or, in general, treating African Americans as second-class citizens, while the Fourteenth Amendment, also adopted after the Civil War, prohibits states, or their local governments, from treating people either unfairly or unequally.

The applicability of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to government sponsorship of residential segregation will make sense to most readers. Clearly, denying African Americans access to housing subsidies that were extended to whites constitutes unfair treatment and, if consistent, rises to the level of a serious constitutional violation. But it may be surprising that residential segregation also violates the Thirteenth Amendment. We typically think of the Thirteenth as only abolishing slavery. Section 1 of the Thirteenth Amendment does so, and Section 2 empowers Congress to enforce Section 1. In 1866, Congress enforced the abolition of slavery by passing a Civil Rights Act, prohibiting actions that it deemed perpetuated the characteristics of slavery. Actions that made African Americans second-class citizens, such as racial discrimination in housing, were included in the ban.

In 1883, though, the Supreme Court rejected this congressional interpretation of its powers to enforce the Thirteenth Amendment. The Court agreed that Section 2 authorized Congress to to pass all laws necessary and proper for abolishing all badges and incidents of slavery in the United States, but it did not agree that exclusions from housing markets could be a badge or incident of slavery. In consequence, these Civil Rights Act protections were ignored for the next century.

Today, however, most Americans understand that prejudice toward and mistreatment of African Americans did not develop out of thin air. The stereotypes and attitudes that support racial discrimination have their roots in the system of slavery upon which the nation was founded. So to most of us, it should now seem reasonable to agree that Congress was correct when it determined that prohibiting African Americans from buying or renting decent housing perpetuated second-class citizenship that was a relic of slavery. It also now seems reasonable to understand that if government actively promoted housing segregation, it failed to abide by the Thirteenth Amendments prohibition of slavery and its relics.

This interpretation is not far-fetched. Indeed, it is similar to one that was eventually adopted by the Supreme Court in 1968 when it effectively rejected its 1883 decision. In 1965, Joseph Lee Jones and his wife, Barbara Jo Jones, sued the Alfred H. Mayer Company, a St. Louis developer, who refused to sell them a home solely because Mr. Jones was black. Three years later, the Supreme Court upheld the Joneses claim and recognized the validity of the 1866 Civil Rights Acts declaration that housing discrimination was a residue of slave status that the Thirteenth Amendment empowered Congress to eliminate.

Yet because of an historical accident, policy makers, the public, and even civil rights advocates have failed to pay much attention to the implications of the Jones v. Mayer decision. Two months before the Supreme Court announced its ruling, Congress adopted the Fair Housing Act, which was then signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Although the 1866 law had already determined that housing discrimination was unconstitutional, it gave the government no powers of enforcement. The Fair Housing Act provided for modest enforcement, and civil rights groups have used this law, rather than the earlier statute, to challenge housing discrimination. But when they did so, we lost sight of the fact that housing discrimination did not become unlawful in 1968; it had been so since 1866. Indeed, throughout those 102 years, housing discrimination was not only unlawful but was the imposition of a badge of slavery that the Constitution mandates us to remove.

Next page