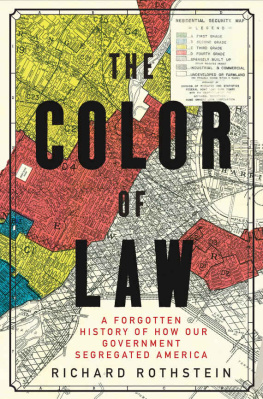

Not in My Neighborhood

Not in My Neighborhood

HOW BIGOTRY SHAPED A GREAT AMERICAN CITY

Antero Pietila

NOT IN MY NEIGHBORHOOD. Copyright 2010 by Antero Pietila. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form. For information, address: Ivan R. Dee, Publisher, 1332 North Halsted Street, Chicago 60642, a member of the Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group. Manufactured in the United States of America and printed on acid-free paper.

www.ivanrdee.com

Maps by Lucidity Information Design

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Pietila, Antero, 1943

Not in my neighborhood : how bigotry shaped a great American city / Antero Pietila.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56663-843-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Baltimore (Md.)Race relationsHistory20th century. 2. RacismMarylandBaltimoreHistory20th century. 3. AntisemitismMarylandBaltimoreHistory20th century. 4. African AmericansSegregationMarylandBaltimoreHistory20th century. 5. JewsSegregationMarylandBaltimoreHistory20th century. 6. Discrimination in housingMarylandBaltimoreHistory20th century. I. Title.

F189.B19A285 2010

305.8009752'6dc22 2009038807

To Barbara,

who told me to write a book

Contents

Preface: Harlem on My Mind

THIS BOOK examines how real estate discrimination toward African Americans and Jews shaped the cities of the United States in which we live. It covers a period from early suburbanization in the 1880s to the consequences of postWorld War II white flight, ending in the first decade of the twenty-first century. The narrative centers on residential real estate practices in Baltimore, Marylands largest city; but, like the city it depicts, the story is all-American. The tools of discrimination were the same everywhere: restrictive covenants, redlining, blockbusting, predatory lending.

A summer-long visit to New York in 1964 sparked my interest in these matters. It was my first encounter with the United States. I was a twenty-year-old aspiring journalist from Finland, a country so homogeneous that eye and hair color marked the chief differences among its four and a half million people. No blacks lived in Finland in those days, and only fifteen hundred Jews. New Yorks polyglot metropolis stunned me. While reporting one day in Harlem, I found myself naked and sweating in an old Finnish steam bath operated by an immigrant from Jamaica. It had been a popular gathering spot among residents of the Finnish community, which thrived in Harlem from the 1910s until the 1950s. Few traces of that population of several thousand survived. Rival socialist halls, including one with an indoor swimming pool and a bowling alley, were long gone, as were Finnish churches.

One vestige still remaining was a hat shop on 125th Street belonging to an elderly Finnish woman, who had stayed after other whites ran. Another relic was the steam bath, with its black owner, a professional masseur, at Madison Avenue and 122nd Street.

Harlem exemplifies succession, which is the sociologists term for ethnic, racial, and economic change. In the space of four decades between the 1870s and 1910s, that section of New York City went from a white upper-class community of American-born residents to one populated by recent Irish, Jewish, German, Italian, and Scandinavian immigrants. Soon thereafter, as a result of white abandonment, Harlem became African American and Puerto Rican, as Gilbert Osofsky chronicled in his 1971 classic Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto. Racial succession is not over, either. Beginning in the late 1990s, Manhattans overheated real estate market made Harlems values so irresistible that whites began returning to live on some streets north of Central Park.

Each transition is different, but one common dynamic is noteworthy: the make-or-break role of real estate agents. In her long-out-of-print 1969 work, Racial Policies and Practices of Real Estate Brokers, Rose Helper examined the prejudices of the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) and the discriminatory policies of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). This book goes further. It also details the stratagems of blockbusters, freebooters who prospered outside the controls of local real estate boards. They sought out declining white neighborhoods near African-American districts. They bought from panicked whites at rock-bottom prices and then resold to blacks at huge profits. Aging populations, the absence of normal ownership rotation due to the unavailability of financing, and a deteriorating housing stock hastened change.

Unlike New York, Chicago, Detroit, Boston, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles, Baltimore is not usually a prominent part of the American urban narrative. It should be. In 1910 the city enacted the first law in American history that prohibited blacks from moving to white residential blocks, and vice versa. When the U.S. Supreme Court seven years later struck down such laws, Baltimore again became a model that other cities copied because private agreements had barred blacks and Jews from certain neighborhoods for years. Until the Supreme Court in 1948 declared them unenforceable, such restrictive covenants were the backbone of residential segregation throughout the nation. Baltimore was also a forerunner in blockbusting. Large-scale, panic-induced racial turnover began during World War II, earlier by about a decade than in many other cities.

From the 1910s onward, neighborhood succession usually happened in the following order: non-Jewish to Jewish to African American. The pattern was due to Baltimoreans embedded aversion to Jews. Whenever Jews started to move in, neighborhoods emptied of non-Jews. If Jewish housing demand then also weakened, such areas became transitional zones where sellers ultimately tapped the black market. The prejudice against Jews was so strong that while separate housing markets developed in many other American cities for whites and blacks, in Baltimore an additional market tier emerged to cater to Jews, who were prohibited by private agreements or custom from living in certain neighborhoods. The three-tiered market was so pronounced that even in the early 1970s a separate multiple-listing service sold suburban homes in areas open to Jews.

Finally, in Baltimore the experiences of an increasingly black city may be contrasted with overwhelmingly white Baltimore County, where the percentage of African Americans declined between 1950 and 1970, even though the countys overall population more than doubled, from 270,273 to 621,077. This book documents how the county contained blacks through zoning and other government actions. During our period of examination, first Spiro T. Agnew and then Dale Anderson led the suburban county. Agnew, who later became Richard M. Nixons disgraced vice president, continued longstanding policies that eradicated old black settlements. Anderson, for his part, in 1972 ordered that real estate agents must report to police any home sales they made to blacks.

The narrative covers some 130 years of neighborhood transition, with an evolving story line that establishes causal links. One such link connects to eugenics, a controversial international scientific, political, and moral ideology in vogue from the 1910s to the 1930s. This book shows how eugenics influenced the federal governments policies and actions. For example, the government redlined 239 cities according to white-supremacist eugenic assumptions that ranked nationalities according to race, religion, and pseudoscientific stereotypes. The eugenic mind-set also guided the Federal Housing Administrations far-reaching policies until the 1960s.

Next page