Preface

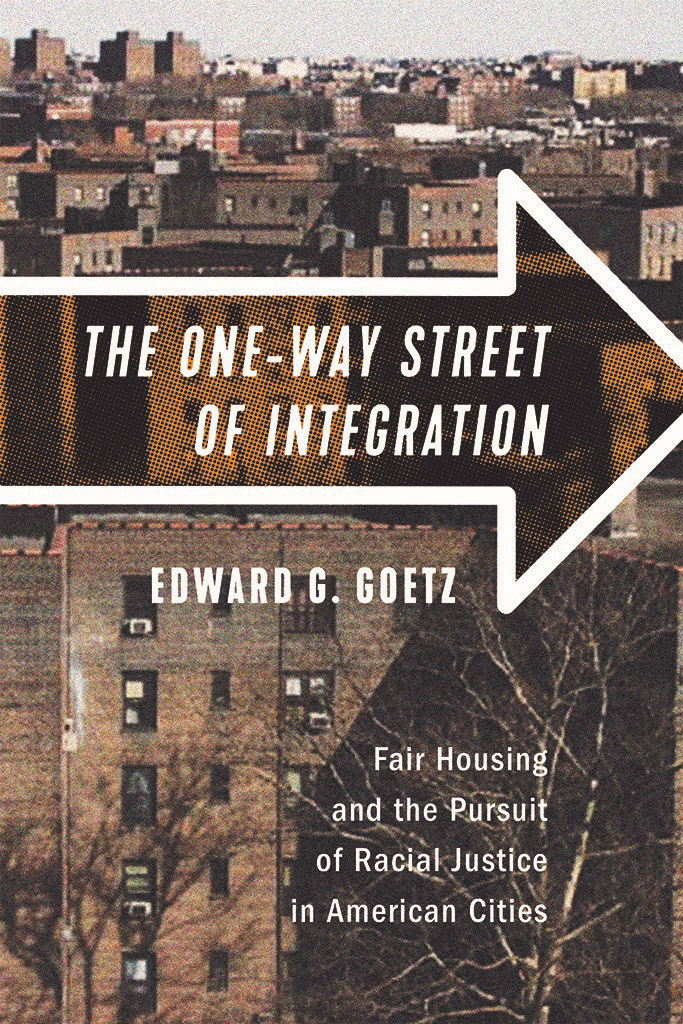

In 1966 Stokely Carmichael wrote in The New York Review of Books that integration has been based on complete acceptance of the fact that in order to have a decent house or education, blacks must move into a white neighborhood or send their children to a white school. This reinforces, among both black and white, the idea that white is automatically better and black is by definition inferior. The solution, he argued, was real power for black people and black communities such that Negroes become equal in a way that means something, and integration ceases to be a one-way street. This expression of the tension between integration on the one hand and community development on the other is as relevant today as it was in 1966. Indeed, given the current policy interest in residential mobility and moving people to opportunity neighborhoods as a way of addressing inequities, and given what I describe in this book as the aggressive spatial strategy of current fair housing advocacy, a renewed examination of the one-way street of integration is well warranted.

Many will no doubt see this book as a lamentable indulgence that has greater potential to foment tension than to explain or resolve it. Most of those people, however, are fair housing advocates who have mounted a systematic and far-reaching challenge to community development and affordable housing efforts. Community developers and affordable housing providers feel themselves subject to attack and thus are a bit more willing to see these issues broadly addressed.

I spent a couple of years working for community development corporations (CDCs) in San Francisco and Los Angeles, served for many years on the boards of directors of two of the most productive and successful CDCs in Minneapolis, and have conducted research on the housing and community efforts of nonprofit organizations. While I agree with fair housing advocates about the need for more affordable housing in white, suburban areas, I disagree strongly with the notion of some in that movement that CDCs are ineffectual in the neighborhoods in which they operate and that their efforts are harmful. This book is prompted by that perspective and also by the fact that I live in a metropolitan area where the debate between fair housing and community development is especially contentious.

I have been assisted by many in this endeavor, though none should be blamed for its shortcomings. Neeraj Mehta of the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs does the work of connecting community development efforts to larger questions of regional equity in the Twin Cities, and as such helps to establish the model for efforts to combat the problems of segregation and inequities of place without setting integration as the solution. He joins many in this work, among them Maura Brown, Owen Duckworth, Caty Royce, and Nelima Sitati-Munene. Their work is the inspiration for mine. I dont know who among these activists was the first to say, Everyone deserves to live in an opportunity neighborhood, but this idea animates the current work, and you will see that I have borrowed the phrase for my conclusion. I am also indebted to the efforts of Jeff Matson, Kristen Murray, Andrew Tran, Tony Damiano, Ned Moore, Malik Holt-Shabazz, and Brittany Lewis at the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs at the University of Minnesota. Many in the housing and community development movement in the Twin Cities, including Alan Arthur, Jack Cann, Greg Finzell, Jim Roth, Deidre Schmidt, and Tim Thompson, have also influenced and encouraged my thinking on these issues. But these issues are salient across the nation, and the book has been spurred forward (knowingly or not) by many outside the Twin Cities, including Chris Walker of LISC, Catherine Bishop of the National Housing Law Project, Michael Bodaken of the National Housing Trust, and Sheila Crowley, formerly of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. David Imbroscio of the University of Louisville and Karen Chapple at the University of California, Berkeley, have helped make the manuscript better, as have the anonymous reviewers and my editor at Cornell University Press, Michael McGandy. I also benefited from the feedback of my favorite civil rights attorney, Sam Hall. Finally, my family, Susan, Hanne, Mary, and Greta, have taken a substantive interest in the book from the beginning and have made their contributions to its completion.

I would also like to acknowledge my cat Squirt for waking me up each morning at four thirty by sitting directly upon my head. This has made for some tense moments between us, but in the end it was always win-winI got up to work on the book, and he got breakfast.

Introduction

ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES TO REGIONAL EQUITY AND RACIAL JUSTICE

There are two realities of American metropolitan areas that concern me in this book: first, patterns of racial discrimination and segregation in housing, and second, the critical lack of affordable housing for persons and families with very low incomes. These two problems have been the subject of much policy debate, political organizing, and collective action over the years. There are interest groups and professionals whose chief activities focus on one or the other. To a large extent, all these groups and professionals share values related to racial and class equity and the importance of housing in providing access to opportunity. On many issues they are allies. This book, however, is about those respects in which the values of these two movements diverge and in fact conflict. This book is about how the pursuit of fair housing can be at odds with the pursuit of affordable housing, and vice versa, and the conditions under which fair housing advocates and affordable housing advocates find themselves on polar opposite sides of issues related to housing, community development, and metropolitan equity.

In this book I address a number of questions central to the tension between fair housing advocates and affordable housing / community development activists. There are critical disagreements that shape the debate. At the core of these disputes are a constellation of issues related to the desirability and terms (for people of color) of integration, the means of achieving integration, and strategies for achieving political and economic justice for communities of color in the United States. Throughout the book I describe and analyze the conditions under which this debate surfaces. Much of the work of these two movements is complementary and compatible, but certain strategies pursued by each bring them into conflict with each other. Identifying when the tensions occur, and why, helps to illuminate the principal elements of the conflict and should provide a means of moving toward resolution or at least toward accommodation between these two movements. I also trace the history of these tensions since the mid-twentieth century, describing how the debate has manifested itself over time and with what outcomes. Finally, I examine the contemporary conditions that have produced a renewal and expansion of the fair housing / community development conflict since the 1990s. It is, in fact, the renewed intensity of this long-standing debate that makes the book relevant and necessary today. In addressing these issues, I argue that we need to move to a vision of urban and racial justice in the United States that does not hinge on the spatial rearrangement of people of color in the manner argued by fair housing integrationists.