Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2020 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54919-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Calfano, Brian Robert, 1977 author. | Martinez-Ebers, Valerie, author.

Title: Human relations commissions : relieving racial tensions in the American city / Brian Calfano and Valerie Martinez-Ebers.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020001205 (print) | LCCN 2020001206 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231191005 (hardback) | ISBN 9780231191012 (trade paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Social problemsUnited States. | Civil rightsUnited States. | DiscriminationLaw and legislationUnited States. | RacismUnited States.

Classification: LCC HN43 .C35 2020 (print) | LCC HN43 (ebook) | DDC 306.0973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020001205

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020001206

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

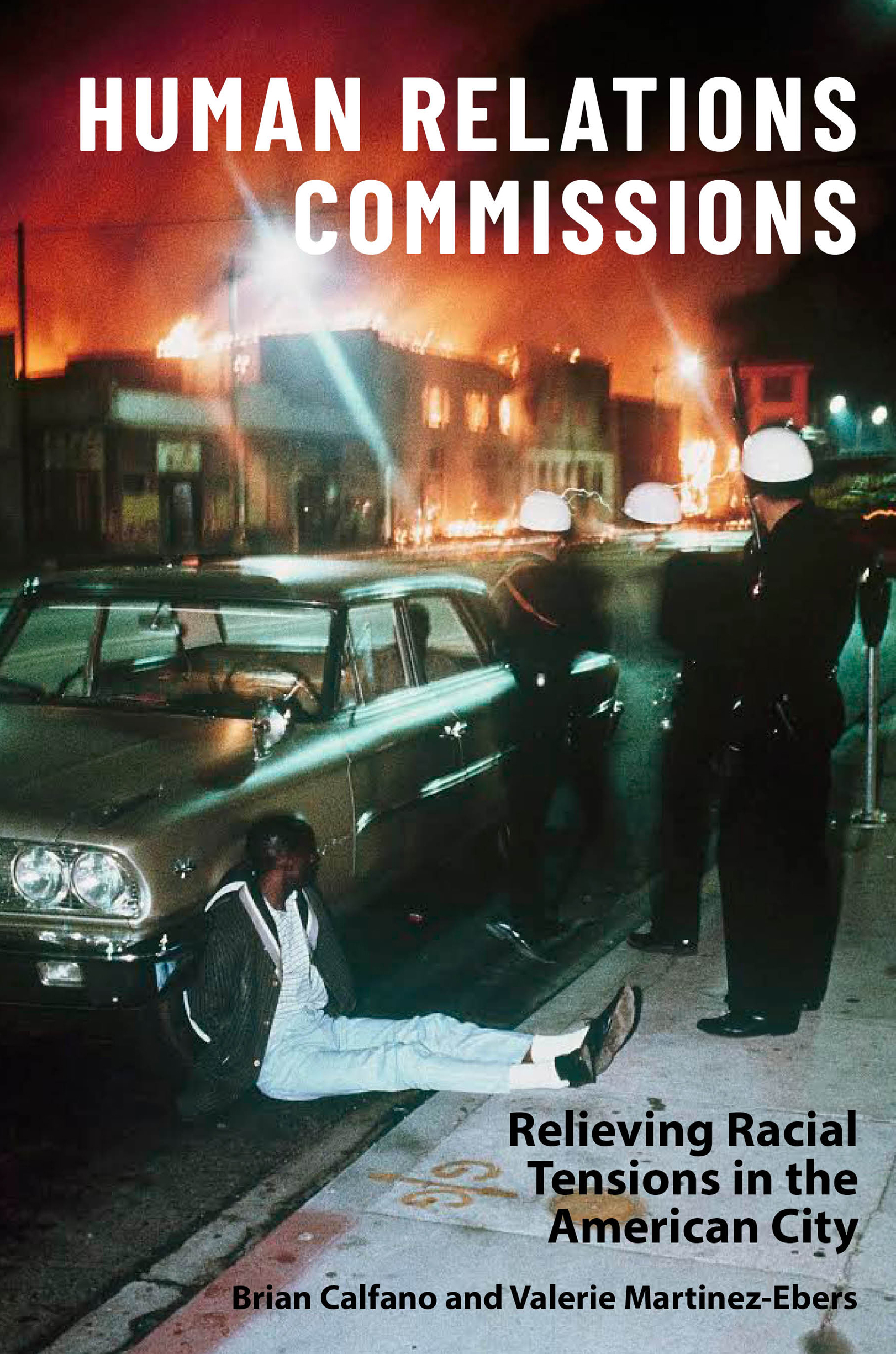

Cover design: Julia Kushnirsky

Cover image: Police keep riots under control in the Watts area of Los Angeles, Calif., Aug. 1965. AP Photo

CONTENTS

N o project of this size comes together without the assistance and guidance of several people and institutions, and this manuscript is no different. We first extend our deepest gratitude to Columbia University Press editor Stephen Wesley for his patience, support, helpful suggestions, and patience (yes, twice). Brian Humes and the National Science Foundation were integral in enabling financial support of the large-scale survey experiment we conducted in Los Angeles. The faculty, students, and staff of the California State University, Dominguez Hills, made particular contributions through their engagement in the research featured in . Colleagues, staff, and students at our home institutionsthe University of Cincinnati and the University of North Texasoffered helpful opportunities to discuss aspects of the manuscript and provided feedback at various stages in the writing process. And we owe a debt to the thoughtful recommendations from the three anonymous reviewers for Columbia University Press who assessed the manuscript at both its proposal and revision stages.

Iris Roley of the Cincinnati Black United Front deserves special mention for her leadership on the Cincinnati Community Perception Survey, which features in . Finally, none of the research would have occurred without the willing collaboration of commissioners, directors and staff with the City of Los Angeles Human Relations Commission, the City of Fort Worth Human Relations Commission, the City of Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations, and the City of Cincinnati Human Relations Commission. Those who work on these commissions give of their time and energies to improve intergroup relations in the communities they serve. It is to them that we dedicate this book.

T he meeting room was filled to the brim with people of varying body postures. Some seemed eager to get a problem off their chest. Others seemed content to simply watch. All appeared to know that what they were about to take part in was about as familiar as a Sunday church service. This community center room had rows of chairs arranged like pews, and chairs also lined the rooms left side. At the front were a couple more rows of chairs facing the audience, but no one was yet in these seats. With the number of people milling about or already seated, several interested parties were left to stand in the hallway to listen for a bit of what this gathering might produce. No one was put off by this. It just seemed to be the normal state of affairs. As the last seat or two filled in, a few attendees huddled closely together whispering intensely about something that seemed like a life or death concern to all of them. Others milled through personal papers or the local newspaper. Several greeted each other with hugs or hearty handshakes. At 10 A.M., as if on cue, a door on the left front side of the room swung open and a line of Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) personnel, including precinct captains, strode in, filling the seats in the front. They were followed by a man in a three-piece suit and cufflinks. Standing in center front, he welcomed everyone, bowed his head, and asked everyone to join in prayer. After invoking the name of Jesus Christ for wisdom and guidance over their work, the latest meeting of the Watts Gang Task Force convened.

For the next ninety minutes, police, community leaders, academics, and local clergy took part in their weekly give-and-take discussion (sometimes you might call it a passionate exchange of views) about issues ranging from the latest altercation between members of rival gangs in one of the neighborhoods four public housing projects, information from LAPD precinct officers on recent arrests and other interactions the department has had with residents, and general discussion of what community members can do to help stave off disputes before they escalate. On more than a few occasions, the discussion was steered by attendees who seemed to command a great deal of respect from everyone in the roomlongtime residents, most of whom had lost children to gang violence in the neighborhood. These people, with lines of experience and pain on their faces and in their eyes, offered a familiar refrain: we have to do something to get Watts out of its rut, especially the violence that robs children of their future.

And, make no mistake, violence continues to plague Watts. The areas median age is just twenty-eight. There are long stretchesmonthswhere the area goes without a homicide, only for innocent residents to be gunned down in sprays of bullets by passing cars. After such tragedies, task force meetings are hotbeds of grief, recrimination, and calls for calm and reconciliation. In many ways, the process is a familiar cycle, with the same participants making the same general statements, and the same police and local officials listening with intent.

But sometimes there is a break in this informal status quo. At one meeting, a Latina and her daughter, neither of whom spoke English, stood at the back of a task force meeting waiting to speak during the open comment period. Both were agitated, tired, and desperate to have those in the room (most of whom did not speak Spanish) understand their plight. An interpreter working for the city walked over to the two and ascertained what was wrong; then the interpreter lifted up a clear plastic bag with some drywall in it. The women had been eating dinner the night before in their Watts apartment when gunfire erupted outside. Bullets entered the apartment and embedded in the walls and ceiling. There was no evidence the women were targets of the shooters, but that did not matter. In a place where they did not speak the dominant language and had few, if any, contacts with community or city services to help guide them through this trying time, the bullets were a reminder of the womens vulnerability.