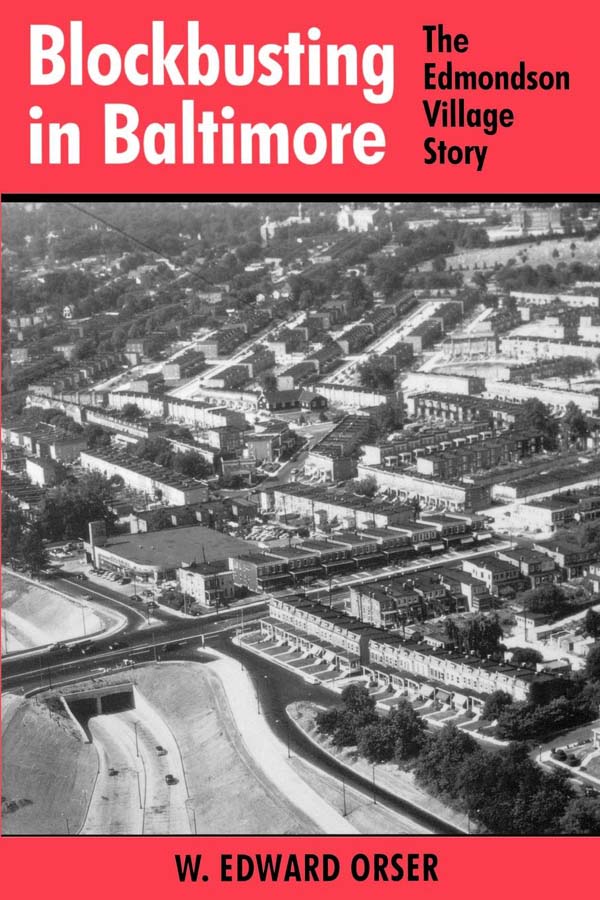

Blockbusting in Baltimore

THE EDMONDSON VILLAGE STORY

W. EDWARD ORSER

Publication of this book was made possible by a grant

from the National Endowment for the Humanities

Copyright 1994 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College,

Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

07 06 05 04 03 6 5 4 3 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Orser, W. Edward

Blockbusting in Baltimore : the Edmondson Village story/W. Edward Orser

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8131-0935-3 (pbk.)

1. Edmondson Village (Baltimore, Md.)Race relations.

2. Baltimore (Md.)Race relations. 3. Demographic transitionMarylandBaltimore. 4. Afro-AmericansHousingMarylandBaltimore. 5. Afro-AmericansMarylandBaltimoreSegregation. 6. Edmondson Village (Baltimore, Md.)Population. 7. Baltimore (Md.)Population. I. Title

F189.B16E266 1994

305.896'07307526dc20 94-8631

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Member of the Association of American University Presses

Preface

Each semester in my course on community in American culture, I suddenly pose this question to the students: Imagine an American community of twenty thousand people; then imagine that ten years later its population is still twenty thousand, but virtually none of the residents are the same; how do you account for that? After looks of initial puzzlement, hands shoot up: A flood or other natural disaster?; A nuclear accident?; Economic dislocationthey all worked for the same employer, and the plant moved? The hypotheses go on, but each eventually is dismissed by the group as relatively implausible. To be sure, some of these ecological or economic crises might produce massive dislocation, but how to account for an equal amount of resettlement? Then someone eventually asks: Racial change? And, invariably, throughout the room there is a collective ohyes, sure!; then class members settle back as if nothing more need be said, because we all, presumably, understand. Each time this happens I find myself reflecting again on what this exercise says about American culture and ourselves as participants in it: that collective behavior based upon dynamics so powerful that they could hardly be accounted for even by catastrophic degrees of environmental or economic impact can be triggered by race, and that such social dynamite is nevertheless so much a part of our cultural surround that we simply accept it as a given, as something that we presume we understandwhether consciously or at some other level of our psyche, and whether we really do or not.

The hypothetical, of course, is not hypothetical at all. It corresponds to the real case of the west Baltimore area called Edmondson Village, where roughly forty thousand people did indeed change placessome twenty thousand leaving, twenty thousand arrivingover a period of approximately ten years, between 1955 and 1965, in an especially acute instance of blockbusting that triggered white flight and racial change on a dramatic scale. As a teacher of American Studies at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, a campus located on the west side of the Baltimore metropolitan region, I continued to encounter references to this particular episode in student family history assignments. Typically they cropped up in interviews with parents or grandparentswhether whites whose families had fled the neighborhood or African Americans whose families had moved in behind them. The range of feelings was wide: among whites they ranged from anger and bitterness to bewilderment and a sense of loss; among African Americans there often were measures of satisfaction with new opportunities but also feelings of disappointment and frustration. The interpretations differed, particularly for those on the two sides of the racially dividing experience, as did assignments of responsibility and blame. But common to all was a sense of social dynamics that seemed beyond individual control and a sense of disjunction, as if their lives had been marked at this one key point by a dramatic experience that still seemed unresolved and a legacy that was uncertain. I came to interpret these references as expressions of, and testimony to, the trauma of rapid racial change, and I set out to try to trace its dimensions.

If the legacy of that trauma is still somewhat unresolved for Edmondson Village residents, past and present, the fact of the matter is that it still is unresolved in many ways for American culture as a whole, because the phenomenon was by no means unique to Edmondson Village. It happened in other Baltimore neighborhoods, in sections of numerous cities, large and small, and in many regions of the United States. In some places they called it panic peddlingbut, by whatever name, it was a process that dramatically changed the shape of Americas urban areas in the postwar decades and laid the groundwork for persistent patterns of race and residency. Despite what we like to feel have been significant changes since that era in legislation, in institutional procedures, and in public attitudes, mechanisms that sometimes may have been more subtle and processes that may have been more gradual nevertheless have continued to produce similar results, if on a less dramatic scale. Therefore, I found it compelling to try to understand the Edmondson Village case for what light it might shed on these larger patterns of race in our national culture, past and present.

Blockbusting, of course, was a logical extension of the pervasive system of residential segregation that American society had craftedby law and by customto create and preserve a dual housing market in American cities, severely circumscribing housing opportunities for African Americans. In the changing social climate of post-World War II urban America a silent conspiracy that had seemed so unshakable suddenly proved exceedingly vulnerable, even fragile. Ironically, it was not ameliorating racial attitudes or institutional reform that produced the transformation as much as it was entrepreneurs out to exploit the crevices in the system for financial gain, profiting at the expense of both populations. One result of such cataclysmic change was rapidly resegregated communities. Whites paid dearly for their decisions to flee; African Americans gained sorely needed residential options, but the toll for them was high as well.

Member of the Association of American University Presses

Member of the Association of American University Presses