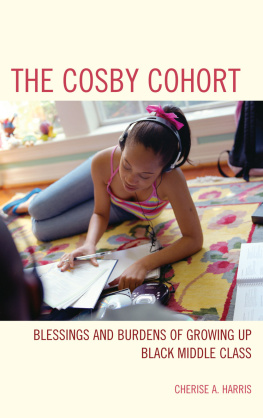

Sherry Lamb Schirmer - A City Divided: The Racial Landscape of Kansas City, 1900-1960

Here you can read online Sherry Lamb Schirmer - A City Divided: The Racial Landscape of Kansas City, 1900-1960 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2002, publisher: University of Missouri Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A City Divided: The Racial Landscape of Kansas City, 1900-1960

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Missouri Press

- Genre:

- Year:2002

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

A City Divided: The Racial Landscape of Kansas City, 1900-1960: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A City Divided: The Racial Landscape of Kansas City, 1900-1960" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

As the African American population grew in size and assertiveness, whites increasingly identified blacks with those factors that most deprived a given space of its middle-class character. Consequently, African Americans came to represent the antithesis of middle-class values, and the white middle class established its identity by excluding blacks from the urban spaces it occupied.

By 1930, racial discrimination rested firmly on gender and family values as well as class. Inequitable law enforcement in the ghetto increased criminal activity, both real and perceived, within the African American community. White Kansas Citians maintained this system of racial exclusion and denigration in part by misdirection, either by denying that exclusion existed or by claiming that segregation was necessary to prevent racial violence. Consequently, African American organizations sought to counter misdirection tactics. The most effective of these efforts followed World War II, when local black activists devised demonstration strategies that targeted misdirection specifically.

At the same time, a new perception emerged among white liberals about the role of race in shaping society. Whites in the local civil rights movement acted upon the belief that integration would produce a better society by transforming human character. Successful in laying the foundation for desegregating public accommodations in Kansas City, black and white activists nonetheless failed to dismantle the systems of spatial exclusion and inequitable law enforcement or to eradicate the racial ideologies that underlay those systems.

These racial perceptions continue to shape race relations in Kansas City and elsewhere. This study demystifies these perceptions by exploring their historical context. While there have been many studies of the emergence of ghettos in northern and border cities, and others of race, gender, segregation, and the origins of white ideologies, A City Divided is the first to address these topics in the context of a dynamic, urban society in the Midwest.

Sherry Lamb Schirmer: author's other books

Who wrote A City Divided: The Racial Landscape of Kansas City, 1900-1960? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.