I would like to thank all the people who helped make this book possible and alsoacknowledge the journalists who gave of their wisdom and allowed me to use some oftheir material. They include Paul Kennedy, Brad Walter, Roy Masters, Mark Fuller,Stathi Paxinos, Brent Read, Debbie Spillane and Steve Mascord. Additionally, I wouldlike to thank my publisher Pam Brewster and my family. I would also like to thankall things Sweet.

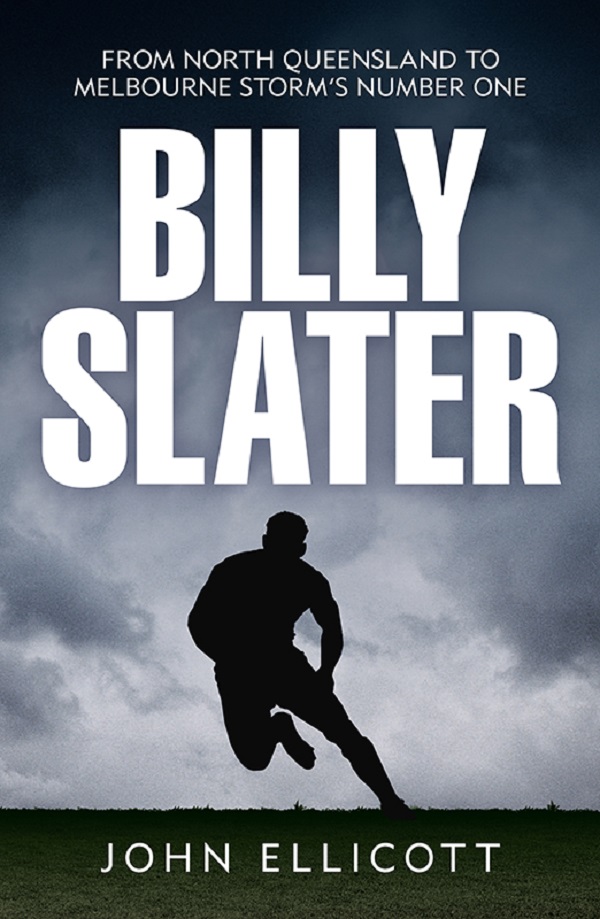

Of all the superlatives used to describe Billy Slater, toughness wouldnt be atthe top of many peoples lists, but that is the first word that enters my mind whenI think of the scrawny track work jockey from Innisfail who has become arguably thegreatest fullback to ever play rugby league.

Having reported on Slaters career from the time he burst onto the scene as an 80kg trialist for Melbourne Storm at the 2003 World Sevens series in Sydney, I havebeen privileged to witness many of the highs and the lows of a remarkable careerin which he has been awarded a Golden Boot as the worlds best player, Clive ChurchillMedal for man of the match in a grand final and Dally M Medal as NRL Player of theYear.

Any tribute to Slater will acknowledge his lightning speed, the amount of groundhe covers in each match, his awareness of when to chime into an attack and the facthe has saved almost as many tries as he has scored.

But the one moment that stands out for me was the determination Slater showed toovercome what was initially diagnosed as a tournament-ending knee injury in the quarterfinal of the 2013 World Cup and play a starring role for Australia in the final atOld Trafford.

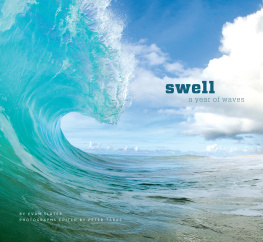

Most players would have just accepted their fate after seeing the way the swellingin Slaters left knee ballooned immediately after being taken from the RacecourseOval in Wales during the match against the USA just two weeks earlier.

Kangaroos physiotherapist Tony Ayoub later described Slaters efforts to not onlyplaybut starin Australias 342 win over New Zealand as the most satisfying momentin more than twenty years of working with club and representative teams.

Australian, Queensland and Melbourne captain Cameron Smith labelled it the best performanceof his longtime teammates illustrious career, which until then had included winninggrand finals, State of Origin series and Four Nations tournaments but not a WorldCup.

Slaters performance and the Kangaroos triumph enabled the then thirty-year-oldto avenge the demons that had haunted him since gifting the winning try to Kiwisplaymaker Benji Marshall in the 2008 RLWC decider at Suncorp Stadium.

While he had bristled at questions throughout the tournament about that incidentbeing motivation for success in the UK, Slater admitted afterwards that he did notreally know if he would last the match but had been so desperate to play he had workedaround the clock to be fit.

For a week leading up to Australias semifinal at Wembley Stadium, Slater barelyventured outside the Royal Gardens hotel on Kensington High Street, where the teamwas based, as he iced his knee and underwent treatment from Ayoub.

In fact, Slater barely left his room as he was hooked up to an ice and compressionmachine for up to eight hours per day.

Yet with just one light training session under his belt before the final, Slaterscored 2 tries in a stunning performance he declared was in the top five of his career.

He later underwent surgery that delayed his start to the 2014 season for the Storm.

Because of his brilliance in attack and uncanny ability to read the play in defence,Slaters toughness is often overlooked, but those other attributes that make himsuch a great player have also made him a target for opposition teams.

To stop Slater wreaking havoc from kick returns, defenders regularly try to smashhim as he receives the ball and he has suffered numerous injuries this way, but bravelytries to hide any pain on the field.

Slater, whose weight has never been more than 90 kg, has had to put up with the tacticfor much of his career. It resulted in him suffering a knee injury in the secondmatch of the 2012 Origin series that caused him to miss the series decider and troubledhim for the remainder of the season and beyond, before eventually threatening hisWorld Cup dream.

Only a special player like Slater could have continued with such an injury for solong, and played so well, that few knew he was troubled by it all.

During that time Slater helped Melbourne to victory over Canterbury in the 2012 grandfinal and set new records for the most tries by any fullback in premiership historyand by a Storm player.

At the same time he has held off challengers for his No 1 jersey in Australian andQueensland teams from two of the best players in the gameGreg Inglis and JarrydHayne, who were forced into the centres during the Kangaroos 2013 World Cup campaign.

While it is hard to compare players of different eras, Slater is not just the bestfullback but one of the best players I have seen in my time covering the game since1994and arguably the toughest.

Brad Walter has covered rugby league for more than twenty years and is the seniorleague writer for The Sydney Morning Herald.

Billy Slater was born to be wild.

Raised in the tropics of Far North Queensland, he grew up with the sometimes dangerousseasons that swung from summer deluges and the threat of cyclones to months of glorioussunshine. It is a landscape that cant be tamed, a place where kids have boundlesschoices to expend their energy, where kids are strong and full of zest and play onevery bit of dry ground they can find. It was a tropical playground for a young Billywho loved swimming, snorkelling, diving and fishing.

The Slaters were battlers. Ronnie, Billys dad, drove trucks taking bananas fromfarms down to the depot in Innisfail for distribution, while his mum, Judy, a toptouch football player, was skilled at packing bananas in record time. They livedon the outskirts of town in Innisfail in a place known as Goondi Bend, where theBruce Highway does an awkward S-turn. It was here, not far from the racetrack, Billywould forge friendships for life. Theyd play together, go to primary school at GoondiState School and then head off to Innisfail High School.

Billy was as energetic and cheeky as kids come. The larrikin streak came from hisdad, Ronnie, known everywhere as Mophead because of his large mop of hair. Billyadded to the tough Slater profile with his wide open smile and his ability to runfast.

In his teenage years Billy was always out skylarking and playing football out ona friends front yard or in the street in the close where he lived. His mates usedto get one of his uncles to drive them up to Mena Creek for a swim, or theyd headoff to Josephine Falls to swim amongst the huge river boulders and dangerous currents.Billy was renowned for surfing down the slippery big rock shelf in his bare feetas the water skimmed over the top, showing off his amazing centre of balance. Billyand his mates also loved jumping off the Kalbo railway bridge into the South JohnstoneRiver. Billy could do a forward flip then a back flip before hitting the water.

His mate Mark Averkoff said Billy rarely had a ball out of his hand. He was alwaysone of the smaller kids, and he loved the kick and chase, eh.