Published in 2014 by Hardie Grant Books

Hardie Grant Books (Australia)

Ground Floor, Building 1

658 Church Street

Richmond, Victoria 3121

www.hardiegrant.com.au

Hardie Grant Books (UK)

Dudley House, North Suite

3435 Southampton Street

London WC2E 7HF

www.hardiegrant.co.uk

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Copyright text John Ellicott 2014

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the catalogue of the National

Library of Australia at www.nla.gov.au

Uncommon Heroes

eISBN 978174 358 2183

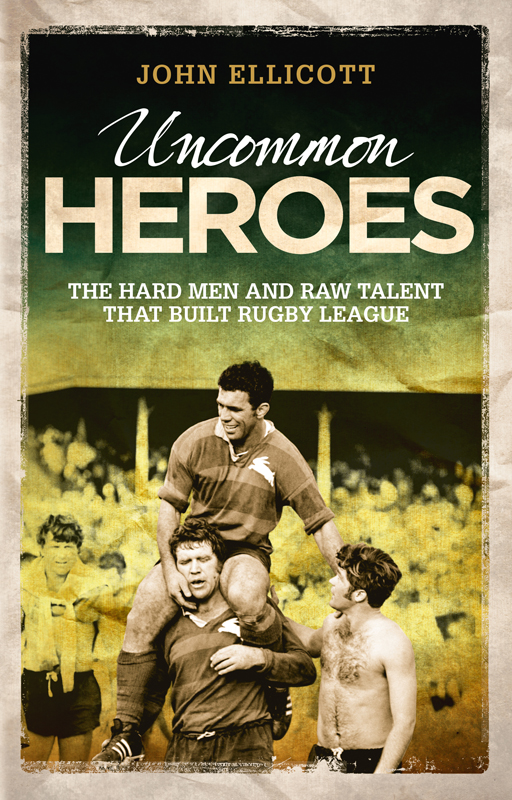

Cover design by Luke Causby, Blue Cork

Text design by Loupe Studio

Cover image courtesy of Fairfax

For those humble in spirit, but who never say die.

Contents

They ran onto sodden fields in ankle-length boots and kicked a wet leather ball that felt like concrete. They fell down like flies but rose from the mud in defiance of their injuries to play onsome with broken bones, or badly torn muscles because there were no replacements. Up to 80,000 people cheered on in the stands, perched precariously just to get a glimpse of the champions. They played for a pittance, and if they finally were given the honour of playing for their nation, they were often away travelling on tour for much of the year only to go straight back into competition when they finally got home. They survived on their wits, natural brawn and the kind of mateship that transcended club allegiances, state lines and national borders.

These are some of the great lives never told from the annals of league. Their names faded like the newspaper clippings of their exploits, kept by friends and fans in dog-eared scrapbooks that few ever saw; great memories kept in the dark.

There was little written on who they were or where theyd come from. Many of their famous jumpers became moth-ridden, or their children wore them to school and sport. Others put their famous jerseys away for good in blanket boxes or in the back of cupboards with match programs and medals.

These were the men of little means who grew up in families that couldnt afford shoes for their children or, like Ronnie Coote as a little boy, wearing a sandshoe on one foot and a galosh on the other. Some players came from towns that arent on the map anymore, from families with fathers who worked in goldmines or carted bread and cut wood to survive. They came from impossible backgrounds to rise into the public spotlight, with their names emblazoned across the sports pages. They became uncommon heroes.

They travelled to training by bike or bus in the hope they could make it to the big time. They dreamed the impossible could become possible. A young man playing in the bush, such as Eric Weissel from south-west New South Wales, could suddenly elevate himself into the realm of international football without ever having played a game in the city. It could happen and it did. Lionel Williamson, raised on a cane farm at the back of Innisfail, could leave his study for the priesthood in Far North Queensland and within a few years don the green and gold for his country and help win a World Cup. Dreams came true, heavens doors opened up.

The ranks of league from the early years were constantly refreshed. The best city players and coaches played in the country during their career and the young men they taught eventually refreshed leagues city ranks. Boorowa, a small town near Yass that was often beset by earthquakes, at one stage had the rumble of Australias front row playing in its league team. Country players were the backbone of the game. And country teams regularly beat their city opponents.

There was a refreshment of the ranks also from overseas. England and the British Lions would play in Cootamundra, Townsville, Tamworth or Toowoomba as part of a tour and put on great displays as the locals gave them a run for their money. An English international would even take up a contract with Grenfell. Just as a Maori tour from New Zealand, way back in 1907, had helped inspire league in Australia (the Kiwis won all three games), so the great Tests and battles for the Ashes gripped the minds of the sporting public, and kept pub conversations going for decades.

The Kangaroos travelled vast distances to play in England and saw unbelievable sights. On the Kangaroo tour of 192930 the players were away for eight months, but what a journey they hadsailing the Pacific and the Atlantic on the best ocean liners, visiting Niagara Falls, meeting the mayor of New York, sitting in the cabinet room at 10 Downing Street with the British prime minister and shaking hands with the Prince of Wales.

England was the mother country for settlement and the mother country for league, but the young Australians, whod taken up league almost at the same time as nationhood, challenged Englands stranglehold on the sport. A tradition was born where players would travel to play for English teams, so many at one stage that the Australian authorities put a ban on transfers. But it was a rite of passage to play with an English cluband the tradition lives on today.

Outside the major competitions in Sydney and Brisbane, there were great league competitions in the regions, followed just as fervently and played just as fiercely. The Maher Cup became one of the most famous cups in any sporting field in Australia and held the attention of a score of towns in southwest New South Wales for 50 years as fans sometimes risked flood and fire to watch games between rival towns. The Maher Cup, known as the Old Tin Pot, was thrown in a river, chucked in a culvert and kept in a police cell as protests raged over who should be its rightful holder. The Maher Cup now sits, lonely, at the bottom of a glass cabinet at the Tumut RSL club, giving little clue to the great celebrations that once went on when a town held it high in the air.

The Foley Shield was the holy grail for footballers of Far North Queensland. The competition spawned many Kangaroos, including Kerry Boustead. Later, its influence on the family of Billy Slater would set the foundation for this amazing footballer, one day voted the best footballer in the world. Slaters dad and uncles played Foley Shield and their guidance helped Billy rise to his great heights for the Melbourne Storm. The Foley Shield was the motivator, the hinge, the fertiliser for generations of footballers. The combatants often played in teeming rain for the right to get into the grand final in Townsville, where a torrid battle always ensued. If Townsville didnt win, the victorious teams from out of town would spend up to a week getting home as they reminisced over their triumph at every little country pub along the way.

The league also boasted vibrant and formidable administrators in its early years. Arch Foley, a friend of Prime Minister Artie Fadden, established league in the north of Queensland. The irrepressible Harry Sunderland led the league in Queensland and then co-managed three Kangaroo tours while also working as a journalist along the way. He helped kick off rugby league in France, pushed for the word league to replace the term Northern Union to describe the game in England, and even tried to promote league to the Americans. They were men of grand ideas and big plans before their time.