For the mothers

Sissie, Patricia, Leslie, Divya, Balamani and Margaret

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand

ISBN e: 978-1-99000-308-0

ISBN m: 978-1-99000-309-7

A Mower Book

Published in 2020 by Upstart Press Ltd

Level 6, BDO Tower, 1921 Como St, Takapuna

Auckland 0622, New Zealand

Text Patrick Skene 2020

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Design and format Upstart Press Ltd 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Designed by Craig Violich www.cvdgraphics.nz

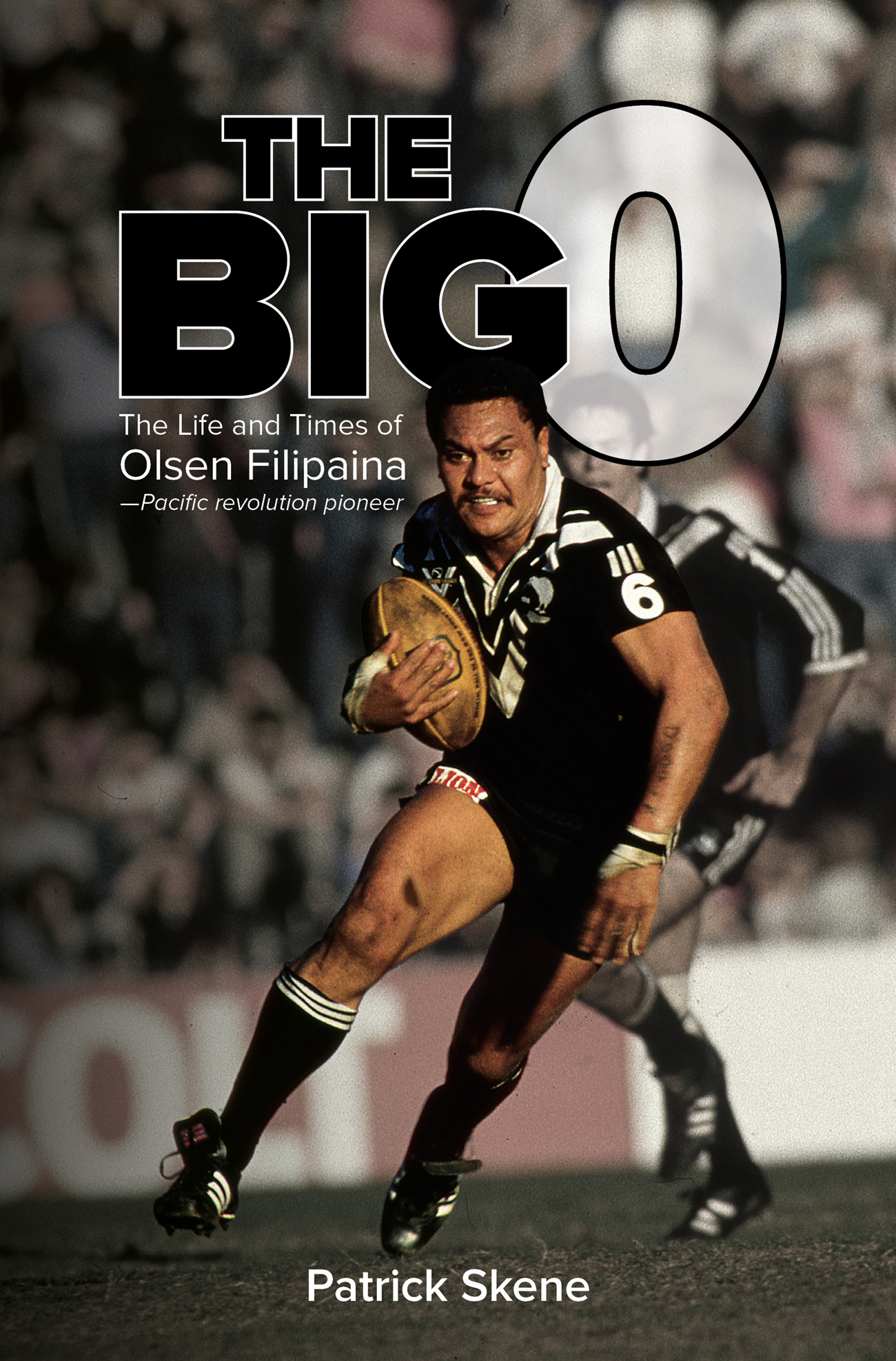

Cover image: NRL Imagery

A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives. Jackie Robinson

Contents

Introduction

Olsen the enigma

Enigma was often used to describe Olsen in Australia and its a shit word it was code for they couldnt figure him out .

Richard Becht, author, historian, Kiwis and New Zealand Warriors media manager

I ts a glorious Sydney spring night and the Wests Tigers are hosting the New Zealand Warriors in the final match of the 2017 NRL season. Both teams are also-rans at the foot of the ladder equal second last and limping to the finish line of a miserable season. The Warriors, who won just one game away from home all season, are about to lose their ninth match in a row.

Yet there is magic in the air at Leichhardt Oval, the traditional home of the Balmain Tigers who merged uneasily with the Western Suburbs Magpies at the turn of the century to create the Wests Tigers. A few times a year for the past 18 seasons, their fans come together at their old headquarters to celebrate and reminisce about their beloved Tiges.

To walk to Leichhardt Oval on match day is to step back in time. Mary Street is a typical Inner West Sydney street, largely unchanged from its early days as a blue-collar heartland. Humble timber and brick, red-roofed cottages perch tightly on narrow streets and lanes. The streets are manned faithfully by fig, jacaranda and frangipani trees awaiting their call to summer bloom.

Built without any parking and with the surrounding streets blocked off by security, everyone walks to Leichhardt Oval following in the footsteps of their Tigers fan ancestors who have walked this same route since 1934.

The air is larded with the smell of boiled hot dogs, sizzling sausages and fried onions from unofficial hot dog stands, manned by spruikers and none more famous than Francis Drake, a match-day institution on Mary Street for 44 years. Hes seen off countless council inspectors and competitors have come and gone, but as a hard-core Tigers fan, Drake lives for Leichhardt Oval footy days.

Every year he and many others are infected with suburban ground nostalgia. Its a yearning for smaller, intimate grounds and the simple pleasure of a tribe uniting on a grass hill. A celebration of a time when rugby league players were of us, among us. They worked in factories, on construction sites, as tradies and as garbos, collecting the citys trash.

Following a team provided a depth of meaning, intensity and identity. The players were ordinary men doing extraordinary things and their stories became living mythology.

Drake smiles as a familiar face walks by with a slight limp, a ghost from his early hot dog-selling days almost 40 years ago.

Tigers old boy Olsen Filipaina returns Drakes smile and nods in acknowledgement but keeps moving, keen to slip into the ground unnoticed, his first time back at Leichhardt Oval for more than a decade.

That guy has sold a lot of hot dogs over the years, Olsen says with a smile. He continues down Mary Street and while there are many outlandish outfits including some Tigers onesies, Olsen is dressed to blend in. Camouflaged in a black and white Adidas tracksuit top, crisply ironed jeans and shiny black dress shoes, he limps towards the entrance.

His aspirations to be anonymous are dashed at the front gate when fans form a gridlock around him, acknowledging an old hero, not with autographs but its digital descendant, the selfie. Olsen meets every request with a smile.

One fan proudly announces that Olsen is still his garbo and that he always comes out of his house to wave as Olsen empties his bin. He was a young boy when Olsen first started his garbage run in Ryde, a community he has faithfully serviced for almost 40 years.

The mobbing fans share their Olsen stories, testing his memory with nostalgic moments. Olsen looks uncomfortable with the fanfare and attention, but he feels the love, saying: I dont get down here much, I try to keep to myself. Im always amazed they still remember me.

Eventually he enters Leichhardt Oval, a hallowed ground in rugby league. A colourful carnival awaits.

He has returned to his old stomping ground as part of Wests Tigers Legends game-day initiative in which the club honours its favourite sons from previous eras.

Another prodigal son is also in the house the crowd swarms around Mori and Tigers legend Benji Marshall who has just announced his return to the club after four years with St George and the Broncos. Benji waves at Olsen and The Big O nods in return and limps on to the corporate function.

*****

As a child, I watched Olsen play at Leichhardt Oval in the early 1980s. He appeared like an intergalactic figure arrived via a portal from another realm. With an unusual name, dark brown skin, big thighs, flashing Polynesian eyes and a beaming smile, he played an exciting style of rugby league the silky skills of a back mixed with the power of a forward. In one of his footy cards he wore a necklace of white puka shells in a proud nod to his Pacific heritage. This we hadnt seen.

To see Olsen play the game of rugby league at Leichhardt Oval was to witness a one-man wrecking ball. It was unprecedented for a man of his size to be fast enough and have the skills to play in the backline. He was a living manifestation of force = mass x acceleration and had a unique method of leveraging his size and power to puncture watertight defences.

His suite of physical assets triggered comparisons to a young Aboriginal Arthur Beetson, who showed extraordinary skills for a big man and also first plied his trade in Sydney for the Balmain Tigers at Leichhardt Oval in the late 1960s.

Olsens opponents in the centres and later at five-eighth would have to contend with a combination of speed and skills that was underpinned by a famous set of big thighs. His powerful-impact game would become his calling card and his thighs his most memorable feature, particularly to those he trampled over.

What made him different to the largely Anglo-Celtic players that came before him was the horsepower he was able to channel from his physical density that seasonally ranged from 95 to 105 kilograms, all piled on a short 5-foot 10-inch/177-centimetre frame.

A nightmare to both tackle and be tackled by, he personified brute force, running over or bouncing off his opponents and creating opportunities for his teammates. His game was built on exceptional strength and power, a low centre of gravity, a love of contact and playing the game with joie de vivre .

*****

Tonight the freshly named Wayne Pearce Hill is a sea of orange and black, the traditional colours of the Balmain Tigers who are resuscitated through their fans wearing thousands of old-school jerseys, the older and more faded the more respect.

The same conversations surface at every Leichhardt Oval match. A shared love of small boutique grounds. How the dilapidated facilities, ancient toilets, wooden benches, rickety grandstands and grass hill are a soothing alternative to the cold, commercial product of large-stadium football. How every year could be the last of their sacred shrine. How commercial reality must eventually trump nostalgia.