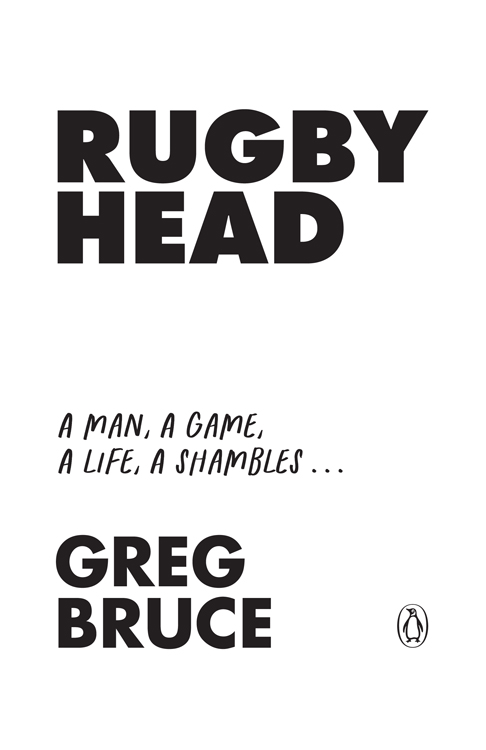

From the triumphs and devastations of All Blacks performances during his 1980s and 90s childhood, his own brief and tortured playing days, his time walking among the games legends as a hospitality worker and failed sports journalist, to his years spent struggling with the recurring torment of World Cup disasters, Rugby Head tackles mental health crises, love, grief, friendship, hero-worship and modern masculinity.

Its the story of a life shaped in ways big and small by rugby, and its greatest team, and all they stand for.

I love this book. Its self-deprecating, for all our stupid selves, and we need that. Its honest, sometimes unexpectedly, like the guest who actually owns up to a fart. Its funny. Its excellently silly, like being tipsy with a great mate. Its sad, when sadness is called for. It sometimes bristles with an insiders disappointment. Maleness. Relationships. Family. Rugby (of course). Being our best, and less than our best. Hoping for better. And its written with such love of words that seemingly effortless cleverness with which Greg Bruce writes.

Introduction

I never doubted I would one day be 45, but it felt so far off, right up until I was 42 or even 43, when I started to look at men in their 20s and realise I would never again be able to wear their pants. Although Id had a lifetime to get used to the idea that I would one day be middle aged, Id spent no time doing so, and suddenly it was too late. The speed with which my life passed roughly doubled between the ages of 20 and 30, and doubled again between 30 and 40. Im not saying Im unhappy with how my life has turned out, just that I thought it would feel more under my control.

Can rugby be said to be like life? Of course it can, and it must, because the existence of this book depends on it. Whenever All Blacks are asked about their first test match, they report how fast it went: they say, I couldnt believe the speed, It went by in a flash, etc. This makes sense. When an All Black debutant takes the field, he is physically, cognitively and emotionally overloaded, dealing with so much sensory information that whatever part of him is responsible for assessing the passing of time becomes overwhelmed, and his ability to locate himself temporally necessarily begins to warp and he comes unmoored.

If youd asked young me where I hoped to be at 45, I expect I would have come up with something quite close to reality: married to the love of my life and best friend, with three adorable kids and a satisfying career, possibly even as a writer, but in the same way an All Black debutant might hear the final whistle and look up at the scoreboard to see his team has won and think, Hmm, yes, seems about right, the result says nothing about the way the metaphorical game was played, or how it felt, or about the periods of darkness before and after half-time when nothing seemed to be working, defeat seemed certain, and the metaphorical French forwards were simultaneously gouging ones eyes and squeezing ones nuts.

This book is an attempt to understand the ways in which rugby and rugby culture have shaped us, and more specifically me. I have always loved rugby. It has thrilled and hurt me, filled me with joy and despair, given purpose to many of my relationships and driven my choice of career. Through the winters of my childhood and youth, and even quite deep into adulthood, my life was heavily influenced by the gravity of the weekends big game. Rugby acted as something like salvation, or maybe just distraction, from a life I frequently didnt much like. My emotional state would rise in line with the news cycle and general buzz of game week, and it would peak, static and crackling, at kick-off. My love for, and knowledge of, rugby was a key part of my identity.

This is the story of my obsession with the game, the pain derived from its frequent failure to deliver the feelings I desired from it, and the search, as I grew older, for a way to find those feelings elsewhere.

Names have been changed to protect the innocent and a few assholes.

No single incident in New Zealand sports history has been written about so frequently and inaccurately. It was in the second minute, or the 20th minute, or 10 minutes into the second half. He had his scrotum rucked. He had his testicles rucked and split open. An errant Les Bleus stud found its way to his groin, where it somehow managed to tear his scrotum, leaving one testicle hanging out. Daniel Dubroca, on the floor, kicked him in the bollocks. Dubroca, trying to kick the ball out of his hands, caught him in the groin. The French laid into him at the bottom of a ruck and his testicle partially unravelled down his leg. He copped a knee right in the nuts. He got kicked in the nuts. He suffered a split scrotum. His sack was split open. He had a torn scrotum with one gonad hanging out.

He chucked the proverbial Jesus water down the shorts to make it feel better. He thought a bit of magic water would fix it. He calmly asked the physio to stitch it up and played on. He had multiple stitches and played on. He asked the doctor to stitch him up and returned until he was later concussed. He had 18 stitches. An overeager pitch-side cameraman filmed the stomach-turning surgery.

While getting changed, after the game, someone across the changing room said holy shit. Someone across the changing room said holy hell. Either Gary Whetton or John Gallagher said holy hell. John Gallagher said holy hell, look at that. He found a testicle a good four or five inches out of the scrotum. His sack was split open and he had a knacker hanging down around his knees. There was fatty tissue all over his legs. The doctor said this is serious, you might not be able to have children. The All Blacks were gagging. It brought a bit of humour to the dressing room. It was all put back into place and stitched up nicely. He went upstairs into a medical room and had it tidied up and put back together. He had 40-odd stitches at the local hospital. He had 46 stitches. He had a shower and then went upstairs to get it tidied up. The doctor told him to pull his Speedos up, so he did, then he had a shower, then he went upstairs to one of the medical rooms to get it put away. He was standing at the bar having a beer two hours later. He had 16 stitches.

He has no memory of it at all. Jean-Pierre Garuet, who he looked up to see flying at him horizontally, had knocked him out earlier. He doesnt know if Garuet knocked him out before or after but he was in la-la land from then on. Garuet knocked him out just before half-time.

He lost four teeth, he lost two teeth, he lost three teeth, he lost a few teeth. Teeth went everywhere. He lost parts of three teeth. He lost some teeth.

In his 2012 book, Buck Up: The Real Blokes Guide to Getting Healthy and Living Longer