Contents

Also by Philip Greene:

To Have and Have Another:

A Hemingway Cocktail Companion

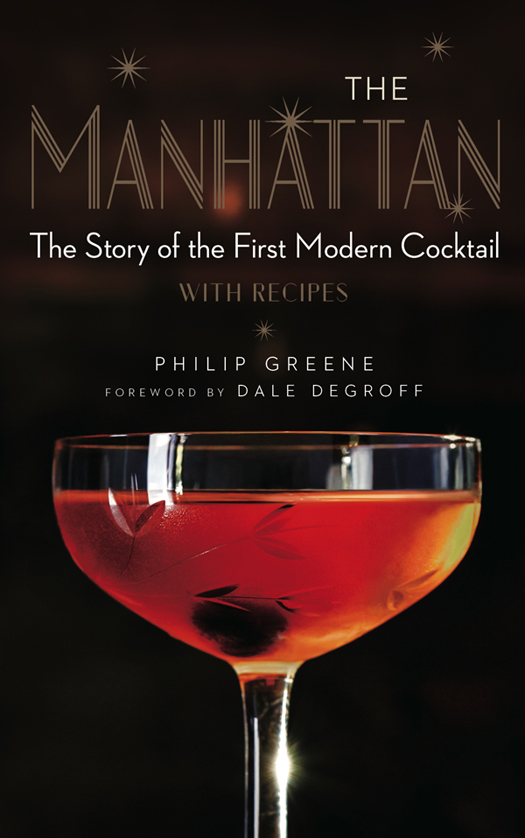

THE

MANHATTAN

The Story of the First Modern Cocktail

WITH RECIPES

PHILIP GREENE

Foreword by Dale DeGroff

Photographs by Max Kelly

at Death & Co., Post Office Whiskey Bar, and OTB

STERLING EPICURE and the distinctive Sterling Epicure logo are registered trademarks of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Text 2016 by Philip Greene

Photographs 2016 by Max Kelly

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4549-3620-6

For information about custom editions, special sales, and premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales at 800-805-5489 or .

www.sterlingpublishing.com

Interior design by Christine Heun

For Elise

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

In 2005a year and a few months short of the 200th anniversary of the birth of the cocktailthe Museum of the American Cocktail opened in the French Quarter of New Orleans. We carefully assembled a group of passionate and somewhat eccentric cocktail authorities, including collectors, historians, a Hollywood graphic designer, spirits experts, writers, and a young trademark attorney from Washington, D.C., named Philip Greene. The goal was to celebrate a truly rich aspect of our culture: the American cocktail. Assembled from our unusual collections of bottles, gadgets and tools, memorabilia from the film industry, and rare books, the inaugural exhibit told the story of the cocktail from the now famous definition in 1806 through the golden years of the 1880s and then Prohibition and into the twenty-first century.

Why open the museum in New Orleans? It was partly because Phil Greenewho, by the way, happens to be a distant relation of Antoine Peychaud of Peychauds Bitters fameargued that New Orleans was the most logical location, the very heart of caf society in the nineteenth century, when migrs from the French Caribbean colonies, Creoles, and Americans gathered in stately saloons and coffee houses. Historians, notably Greene among them, have since established that, despite lore still circulating there, the cocktail wasnt born in New Orleansbut that doesnt matter. The drinking culture of the Crescent City is so integrated into the experience for visitors and so integral to New Orleans culinary culture that theres simply no contest. Its absolutely the perfect place to celebrate the distinctly American culinary tradition of the cocktail.

Many cocktails are native to New Orleans, but the one on which Mr. Greene has set his sights in this book is decidedly not one of them. New York City lays claim to the Manhattan, but is that claim valid? Greenes detective work takes us on a journey that unearths entertaining bits and pieces from newspapers around the country. He builds a colorful tapestry of politics and invention that illustrates the impact that one cocktail had on cocktail culture at large, even showing how that other icon, the Martini, may have spun off from the Manhattan.

In The Joy of Mixology, Gary Regan floats the idea that the Manhattan is more than a recipe; its a category. With the exception of the Old-Fashioned, the Manhattan is arguably the most successful and the longest lived of the strong, stirred cocktails. Greene gives us the formula that illustrates the jump from old fashioned cocktails to the new, the modern, when he quotes Theodore Proulx, author of The Bartenders Manual:

Manhattan Cocktail

This is made the same way as any other cocktail, except that you will use one-half vermouth and one-half whiskey in place of all whiskey, omitting absinthe.

Greenes point is reinforced in O. H. Byrons The Modern Bartenders Guide. Byron provides two Manhattan recipes and this one-line note instructing bartenders how to prepare the granddaddy of the Martini:

Martinez Cocktail

Same as the Manhattan, only you substitute gin for the whiskey.

Bartenders have returned over and over to this modern cocktail formula for inspiration. Greene mines that rich ore of Manhattan variations and shares those riches in a cornucopia of drinks that vie for a piece of the Manhattans glory. Some variations embrace the outer boroughs, the Brooklyn and the Bronx for example, others the more recent trend of taking their names from the neighborhoods of New York.

Among my favorites is Vincenzo Erricos Red Hook, the variation that began the neighborhood-versus-borough battle. That drink wonderfully pairs the spicy Carpano Punt e Mes with rye whiskey. In a later recipe for the Bushwick variation, Phil Warda veteran of three great cocktail bars: Pegu Club, Death & Co., and Mayahueluses Carpano Formula Antica, not available when the Red Hook graced the Milk & Honey menu. Chad Solomon, a craft bartender who cut his teeth under Audrey Saunders at Pegu Club, introduces Cynar, the Italian artichoke aperitivo, to 100 proof bourbon in his variation, the Bensonhurst. The two get along so well that the Bensonhurst has been welcomed onto cocktail menus far beyond the Brooklyn neighborhood, as have many of the other variations in this book.

What makes The Manhattan so entertaining is Greenes light touch, sense of humor, and above all his passion for the subject and all its colorful history. With this compelling, well researched volume, Greene joins a small but distinguished group of drinks historians that includes Gary Regan, David Wondrich, Ted Haigh, Jeff Beachbum Berry, and Lowell Edmunds, among others, and I for one look forward to accompanying him on his next journey of discovery.

Dale DeGroff

The Chrysler Building at night

INTRODUCTION

MEET THE MANHATTAN

There is no such thing as bad whiskey. Some whiskeys just happen to be better than others. But a man shouldnt fool with booze until hes fifty; then hes a damn fool if he doesnt.

William Faulkner

For the vast majority of the nineteenth century, the cocktail, that iconic American invention, was a simple affair: Defined in 1806 as spirits of any kind, sugar, water and bitters, it lumbered along in workmanlike fashion, varied only by the type of spirit or bitters used. A whiskey cocktail, brandy cocktail, gin cocktailall essentially were the same, and none merited a more particular name. In the 1830s, the landscape got a little cooler with the arrival of ice, but other than that not much innovation was taking place. When Dick & Fitzgerald published the first bartenders book in 1862, Jerry Thomass How to Mix Drinks or the Bon-Vivants Companion, only ten of the concoctions were true cocktails. The rest were versions of punch, that centuries-old stalwart, along with cobblers, daisies, juleps, sangarees, smashes, sours, and other kinds of libations. All fine drinks, mind you, but they lacked a certain sophistication and liquid eloquence.