To Glynis, Anker, and Tessa

CONTENTS

Why did you want to make vermouth?

The gifted wine and spirits writer Amy Zavatto asked me this question during an interview for an article about my reserve vermouth. Its not the first time Ive been asked this, and I love it every time. Now that Ive written this book, I expect to be asked the related follow-up: Why would you write a comprehensive book on vermouth? Also a great question, and one that Id like to answer right from the start.

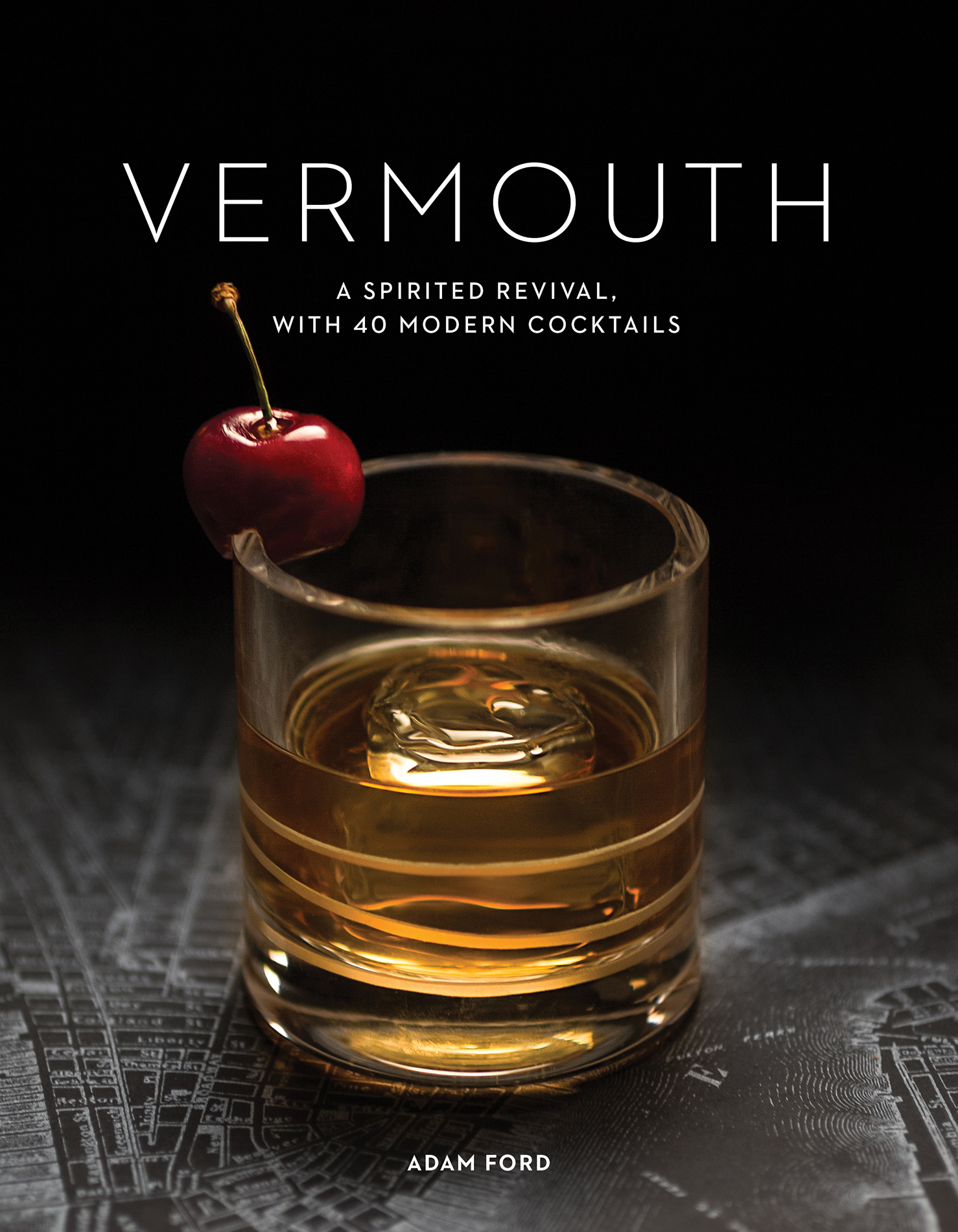

I wrote this book because I fell deeply in love with a delicious aromatized wine while walking through the Italian Alps. And that led me to create Atsby Vermouth, which was my first attempt to accomplish the Platonic ideal of a perfect vermouth. Then, while creating my two signature expressionsArmadillo Cake and AmberthornI engaged in David Wondrich-esque research on vermouths rich history and realized that the story of vermouth in America had never been told. And the story of vermouths ancient history as it has been reported for the past several years is filled mostly with factual inaccuracies. Despite vermouth being the height of drinking sophistication for generations, its dizzying fall from grace and its rise from the ashes like that rainbow-plumed phoenix in the past couple of years, no one has set this saga to writing. Given that I did the work and had all this information swirling around my mind, and that in the past two years the category has catapulted from laughing-stock to the center of cool, mature sophistication, it occurred to me that it was high time that someone tell this story. To quote Bob Dylan (who provided much of the soundtrack to my writing sessions), I guess it must be up to me.

The backstory of Atsby Vermouth is a simple, non-traditional love story. My wife, Glynis, is second-generation Italian and grew up old-school. On most nights before dinner, as a little girl, she saw her mother and stepfather enjoying sweet Italian vermouth in a nondescript tumbler. On special occasions, such as the Christmas Eve Feast of the Seven Fishes, when the house was filled with friends and family, the fireplace crackled, and garlic, marinara sauce, and fresh fish permeated the air, her mother would give her a small glass of her own (more like a taste). But those sips, as minuscule in volume as they were, burned into her mind an association of vermouth with the feelings of joy, love, and celebration with friends and family.

Glynis and I had our first date at an old speakeasy at 86 Bedford Street in the West Village (the building crumbled a few years later). She ordered a glass of sweet vermouthchilled, updisplaying rare style and confidence. Who orders vermouth? I thought, and was immediately drawn in by the mystery. I asked her about it, and she responded nonchalantly that it was a drink to have with people you feel connected to. She paused, then added, And I can drink it all night without worrying about how I might behave later. Her tone was sophisticated but not fussy.

I had never tasted vermouth, nor was I interested. I thought I looked cool pouring a dash into a martini glass and then dumping it out. My parents were hippies and didnt drink such old-timey stuff. It had never occurred to me to give it a chance. In the bar that night, I ordered a bottled beer. (The place was historic, surreal, idyllic, but lets face it, the taps hadnt been cleaned since Prohibition.) But I quickly questioned my choice because she came off as so much cooler and more confident than I did.

That first date evolved into moving in together, marriage, and then the financial devastation that would lead to the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy of September 15, 2008, during the aftershocks of which we decided to get away from Manhattan for a while. We set out to hike the Tour du Mont Blanc, which circles the largest mountain in Europe through France, Switzerland, and Italy. We bought a plane ticket online, took off of work with only two days notice, and were in Geneva the next morning. We took a fast, clean train to Chamonix, and, wearing far-too-heavy backpacks, we bought a map at an outdoors store and a pound of Morbier (really stinky) cheese and a baguette at a corner shop, and walked out of town and toward fields of high grass and mountain wildflowers, opting to bypass the gondola that takes walkers to the top of the first big climb.

We spent a few days hiking over glaciers and snowfields. In mountain huts we slept next to strangers whose language we did not speak, and whose odors were different than ours. When we got back down into the Aosta Valley about a week later, in the serene mountain town of Courmayeur, we rewarded ourselves with a fancy hotel room and an expensive dinner at a small side-street caf, a little bit off the main town square. During dinner, my wife noticed that others in the restaurant were drinking vermouth, and of course she ordered a glass. We had never seen the brand before. She took it cellar temperature in a classic Italian wine glass, like everyone else, and loved it.

For the first time I tried it too, and found it unlike anything Id ever drunk before. The flavors were intriguing, enigmatic, and distended. I asked the bartender (in Spanish) what the ingredients were and he told us (in Italian) thatas with all vermouthsit was a highly guarded secret, but that everyone had their opinions as to some of the ingredients. An Israeli couple next to us overheard and suggested a few possibilities: Maybe gentian? Or angelica? Certainly some cinnamon. The night ended with a list of almost a dozen potential candidates that I wrote down on the back of a napkin, sadly long since lost.

We closed out the restaurant, and despite the amount we had drunk, we walked back to our hotel room still sober and excited, holding hands like a couple of junior-high kids. While I looked at her and she looked toward the stars, I asked Glynis what she wanted to do when we got back to America. She said she wanted more nights like the one we had just had. More joy talking to strangers and learning new things. More feelings of connectedness and passion and excitement about things to come. Carrying the warmth from that evening, we finished hiking around Mont Blanc and made it back to Rougemont, Switzerland, where an art collector friend warmly welcomed us. He took us out for Raclette to fill us up and replace some weight we had lost.

When we returned home, for many nights we cooked the simple meals we had eaten along the walk through Italy: sauted wild mushrooms over polenta, sliced flank steak over a bed of arugula, and Parmesan sprinkled with freshly-squeezed lemon juice. Each meal started with a glass of vermouth. What we were able to purchase back in America, however, was nothing like what we had experienced in Courmayeur. I thought the vermouths we purchased and were drinking were mediocre, at best. They paled in comparison. They were like buying a suit off the rack after years of having tailor-made; it was fine, but you didnt feel like you were at the top of the food chain. One night, perhaps searching for that ineffable feeling, Glynis made the offhand comment of how wonderful it would be to be back in Italy drinking that vermouth on that side street off the town square. That vermouth, we both knew, even if we never said it, had so much more flavor, so much more intensity; it filled our mouths with joy and secrecy. She asked why we couldnt bottle that feeling. Then it struck us. We could create a new vermouth, an Americana-styled one that both improved upon the European brands found in America and reminded us of that perfect evening in that sublime mountain town.

Next page